from Instagram

GAF stencils and banner drops! WE WANT EVERYTHING!

from Dreaming Freedom Practicing Abolition

Stephen Wilson is a Black queer abolitionist writing, organizing, and building study groups and community behind the wall at SCI-Fayette in Pennsylvania. Ian Alexander is his friend and comrade on the outside. This interview is the first in a series that will be published together as a zine.

Ian Alexander: When and how did you become an abolitionist in your thinking, and how did you become an abolitionist in your practice?

Stephen Wilson: These questions reminded me of some anecdotal advice Mariame Kaba gave organizers first encountering a community or group. She talked about how important it is to be a noticer, to observe what is already there. Often, we enter communities revved up to teach and show and convey. But if we took the time to observe and learn, we would see that there are ideas and practices already in place that are abolitionist, even if the people don’t call them that.

Before I ever read any abolitionist theory, I already had some abolitionist ideas. Before I called my praxis abolitionist, parts of it already was. I have often spoken about how the ballroom community prepared me for this work. It was within that community that ideas about non-disposability and centering the needs of the most vulnerable/impacted were first taught to me. It was within that community that I first learned about mutual aid. We didn’t call ourselves abolitionists, but we were practicing it.

My conscious embrace of abolitionist theory occurred soon after reading issues of The Abolitionist and having conversations with Jason Lydon at Black & Pink. Critical Resistance-New York City sent me lots of materials to read and answered tons of questions. Before this time, I was more of a disillusioned progressive. I knew we could create a better world but was frustrated by the tools and means at our disposal. No matter what we did, the system was changing. Not real change. It never occurred to me that we could do away with the entire system. That the system itself was the problem. Abolitionist theory created new possibilities. It opened new ways of seeing and being. It wasn’t a tough leap for me from progressive to abolitionist.

Practicing abolition is harder, especially behind the walls. Abolition is not supposed to be an individual exercise. It is about community, about connection. And that is what makes it hard in prison. We are conditioned and encouraged to separate, isolate and differentiate.

IA: Could you say a little bit about the difference between “progressive” politics and abolitionist politics?

When I say progressive /reformer, I am referring to a mindset that couldn’t see beyond or outside of the system. A mindset that lacked imagination and viewed the system as necessary to solve our problems. I couldn’t imagine the work, whether it was on educational, public health or social justice issues, being done outside of the system. So I found myself frustrated but constantly pushing for tweaks to make the system more responsive. I couldn’t see that the system was the problem.

Abolition broadened my imagination and helped me to see outside of the box/system. It also restored my faith in us. I believe we can keep each other safe. I believe we can provide for each other. I believe we are enough. I now know that the system was never broken. It was doing what it was meant to do: control, surveil, punish and kill us. No amount of tweaking will change that. Now, I see the need to abolish the system and create new relations. As long as one works within the strictures of the system, that world will be impossible.

IA: What were some of your hurdles, struggles and frustrations early on? How did you overcome those–and how have you still had to fight to overcome them?

SW: I knew that in order for me to deepen my practice I needed a community. So I began to reach out to others, extending myself. Abolitionists must extend themselves. I passed out literature and formed discussion groups. And none of this would have worked if I hadn’t been really striving to show abolition to others. In prison, we have a saying: “Believe nothing you hear and half of what you see.” So people are looking and they are keeping tabs. Are you really about what you say? Especially when adversity strikes? So practice was necessary. And being in here, in this environment, definitely forced me to deepen my practice.

One of the earliest big hurdles I had to overcome was materials. The prison isn’t going to provide us with radical, transformative materials. I had to find sources to provide us study materials at low or no cost. Reaching out to presses and zine distros enabled me to procure materials. Without materials, there is no study group. This hurdle is often the biggest one for prisoners who want to start a group.

Connected to this issue is the matter of accessibility. So much of what is written isn’t accessible to most prisoners. Sometimes, it is a matter of forum. There are very informative essays, articles, panel discussions and excerpts online. Prisoners cannot access these materials. This barrier keeps us uninformed and out of discussions. Another accessibility issue concerns writing style. Often, there is no way into the text for prisoners. I am reminded of Ruthie Gilmore’s statement about thinking theoretically but writing/speaking practically. She talks about writing like you want to be read. So many people are writing like they don’t want to be understood by the masses. If people need a dictionary or encyclopedia to read your work, they most likely won’t.

To overcome the obtuseness of texts, I found myself “translating” materials for our study groups. The message contained in the texts was beneficial, but I had to explain what the message is to others. Without understanding there is no application. It was frustrating but it made me better. I learned how to create good discussion questions. I learned how to connect the readings to real life situations and encourage application. It made me and the group participants more critical thinkers.

IA: How do you start a study group in a prison?

As I said before, without materials there is no study group. So it is important that we find sources for materials. That is step one. Sometimes, you already know what you are looking for. You may want to study Black liberation struggles. So you contact a zine distro or press and request materials relevant to the topic. Other items, you don’t have a particular topic so you can request a catalogue from a distros that covers many topics. I would suggest ordering a catalogue.

It is important to talk to participants or potential participants about what they are interested in studying. Even if one feels some other topic is more important, it is important to start where the people are. So even though I feel patriarchy is a topic everyone inside needs to study and tackle, I didn’t start there. I had to get people interested in and acclimated to study. That meant meeting them where they are. Prison issues and racism are easy entry points to studying. From these topics, one can springboard to other issues.

Starting a study group means spending some money. Even if you get the zines for free, you have to pay for copies. In PA, we aren’t allowed to receive multiple copies of any publication in the mail. So people cannot send a prisoner two copies of any book, journal or zine at one time. This means I usually received one copy of a text. I had to make lots of copies for the groups. That costs. Then, there are supplies. Martin Sostre opened a bookstore in Buffalo. He wanted it to be a learning site for people, especially the youth. And it was. He made it easy for them to learn. He provided a space. He provided the materials. All at no cost. So they kept coming back. I had to do the same thing. I had to cover all costs for the groups. That means composition books, pens, pencils, folders and paper costs had to be covered. And as the groups grew, so did the costs. But the upside is that the groups grew. We made studying easier for the people so that is what they did.

IA: What is the role of outside support in all this?

SW: Outside support is critical to maintaining study groups. We need material support as well as guidance regarding how to handle group dynamics issues. We were/are fortunate to have a strong support circle that provides both for us. Without them, we couldn’t do this work.

IA: What are your goals going into a new study group? How do you inspire interest in new and potential comrades?

SW: Choosing study materials is a combination of assessing where the people are and the particular needs of the environment. Choosing materials for a group of people who are already readers and who like to hold discussions is very different from choosing materials for people who haven’t been exposed to such activities. Likewise, there may be particular issues at a site that make studying certain topics more important and relevant. Here , at SCI-Fayette, which is built on a toxic site, materials on environmental racism and environmental justice resonate with prisoners. This topic may be the gateway for many prisoners to studying other issues. The point is that the choice of study materials is always connected to where the people are and what is happening there.

IA: What role have teaching and mentorship played in this process for you?

SW: In the beginning, I did assume a leadership role. But it wasn’t leadership in the sense of making decisions for everyone or having authority over others. It was leadership that was grounded in responsibility. I felt responsible for the groups. I had a commitment to nurture and grow them. I knew I needed help and readily reached out for it. Also, I tried to get people involved and taking responsibility for tasks. I wanted them to own the groups. Then they would care about them.

It is important to cultivate leadership inside. At any moment, any of us can be transferred. So it is important to plant seeds and tend to them while you can. This is one area we need to do lots of work on inside. We have to work harder to create a network of people inside who can create and sustain study groups.

IA: What makes a good abolitionist teacher?

SW: Being a noticer is important. We have to notice who is doing what and how. At Smithfield, I had spent years cultivating relationships and a reputation for sincere concern for others. This made it easier for me when I began groups. People already knew and trusted me. When I came to Fayette, I didn’t have that history. There were people here who knew me from Smithfield and there vouching for me helped tremendously. But I spent time noticing who was doing what. I noticed who was in the dayroom reading. I listened to conversations. And people watched me too. A few guys came up to me and told me they overheard my conversations on the phone. I had been talking with other abolitionists. What they heard piqued their interests. They also saw what I was doing. Mutual aid is major inside. Nothing speaks like action. They saw me practicing abolition. They saw me practicing mutual aid. They saw me practicing solidarity. These acts opened the people’s hearts to me. I can honestly say that I have received just as much respect and love from prisoners here that I did at Smithfield. I know that this mutual love and respect is built on knowing and being present for each other.

IA: How do you start to build relationships with new people on your block?

SW: There is nothing like face to face organizing. To be there, in the trenches, with others, struggling and organizing together builds bonds of trust and care. There are people behind these walls whom I have organized with that I will always feel a deep connection to. We are in the belly of the beast. And when others stand with you inside of this place, it creates something special between you.

To organize inside, you have to be a people person. You cannot be shy. You have to notice things. There have been times when I hear young prisoners talking about something and I listen for a while. Then, I ask questions. Asking questions is a great way to enter a conversation. Interjecting with a statement is risky. Making declarations, especially when they contrast the participants stance, can lead to arguments and accusations of not minding one’s own business. But when you ask questions, especially those requesting more info or clarification, it allows the young prisoner to be heard and express his/her views. This doesn’t happen too often for them inside. It seems everyone wants to tell them what to do and think, but who is listening to them? I do. And because I do, they listen to me.

Also, being open to feedback and criticism is important. Be human. Don’t try to come off as a know it all or like you have all your shit together. When I found out that Maroon was here in the infirmary, I was looking for a way to connect to him. I knew the barbers go to the infirmary to cut hair. When I went to the barbershop, I struck up a conversation with a baber and asked him if he knew Maroon. He didn’t, but he knew whom I was talking about. He had seen him. I gave the barber some materials, including Maroons’s The Dragon vs. The Hydra essay. I told him to send my love to Maroon the next time he went to the infirmary to cut hair. I also told him how I wished I could spend time talking to Maroon about his work. That was enough to spark the barber’s interest.

The next time I went to the barbershop, the barber excitedly told me how he had spoken to Maroon a number of times since our last appointment. He told me how they discussed the essay too. I was so jealous! But what stuck with him the most, and this is according to his own words, was how Maroon remained humble. He was amazed that this elder who had spent so much time in the trenches still felt he has so much to learn and still needs to grow. The barber told me he expected this elder to act like he had it all together, all figured out. But he didn’t. The barber told me how Maroon inspired him to always study, keep learning and keep growing.

The point is that we, organizers and activists, our behaviors and attitudes, are determining factors in how far and wide abolition can go. This is why the internal work of abolition is so important. That’s why the presence aspect of abolition is key to expanding the awareness and the possibilities of abolition. As I said before, prisoners believe nothing they hear and half of what they see. We have to make that half count. To riff off a Lisa Nichols quotation I read years ago: Abolition is not just what you feel or what you say. It is what you do. So what are you doing?

IA: How has COVID-19 impacted your work?

SW: COVID19 affected our ability to meet face to face as much as we would like to. But it didn’t stop us from studying. We issue composition notebooks to everyone. We provide copies of the reading materials and discussion questions. Participants can submit their answer by writing in their comp books and turning them in for feedback. We are able to comment on each other’s answers and leave our own comments.

It became much more like the inside/outside study groups we have in which we read and discuss materials with outside allies. The point is that study never stopped. Moreover, I found that there was an uptick in interest. With the prison’s normal operations shuttered, people are looking for other things to do. The normal distractions, TV and tablets, become boring quickly. I have been disseminating lots more materials since the viral outbreak.

IA: How do you inspire long term interest and growth in new, old, and potential comrades?

SW: Really it has never been about them trusting me because they haven’t heard of abolition. It is about getting them to trust themselves and their communities to handle harm without calling the cops. Part of our task is convincing people that we have within us the resources to handle harm. We can make us safe. For so long, people have been told only the cops can make us safe. Only prisons can keep us from being harmed. People are starting to see that cops don’t produce safety. All of the police violence captured on camera is making people question the supposed link between cops and safety. We need to do more to get people to see that prisons don’t produce safety either. Because the quotidian violence of prisons is mostly hidden from the public this task becomes harder than showing that cops don’t make us safer. One of the biggest obstacles in abolitionist organizing behind the walls is convincing people that we can keep each other safe.

IA: You have told me a lot about the importance of history, and seeing yourself as part of a tradition. Could you talk a bit about that?

SW: If we don’t know the movement history, if we don’t know the elders and what they have accomplished, we will find ourselves stuck in old problems, spinning our wheels, and attempting to enact failed solutions. I love studying movement history and elder bios. I find inspiration. I find strategies and tactics I can adopt or adapt. I find confirmation. And that’s important too. Sometimes, we wonder if what we are doing is worth it. Reading movement history and elder biographies convinces me that it is. There have been times when I have faced repression from prison officials and began to feel depressed. During those times, I reflect upon what so many others have endured and my spirit is comforted and emboldened. Reading about people like Martin Sostre, who was wrongly arrested and sentenced to nine years because he educated the people, keeps my head up during these periods of repression. Many of our elders have been physically, mentally and emotionally abused, but they remained strong. History becomes a living tool.

Oppression breeds resistance. And often, resistance breeds more oppression. It is a dialectical relationship. Behind these walls, oppression can take many forms: solitary confinement, physical assault, constant shakedowns, constant transfers (diesel therapy), destruction of property, denial of parole and even frame-up on new charges. The administration will employ many different measures to effect compliance. They don’t want us to learn anything that will keep us from coming back to prison. They don’t want us to learn anything that will enable us to benefit our communities. I have said before: a learned prisoner is an affront to the PIC.

IA: So beyond study, what about struggle? How do you decide when to really jump into action, and when to wait something out?

SW: How do I decide when something is worth it? Is it the right thing to do? That is the question. I don’t tend to think about what the administration will do to me personally. Because the tactics I use aren’t those that will give the administration grounds to oppress us, tactics that knowingly subject others to possible harm by officers, my main issue is doing what is right and alleviating oppressive conditions. Recently, I have been thinking about developing a criteria regarding when we implement action plans.

This new way of thinking occurred to me after a recent incident. We are not under normal operations. So our time out of cell has been curtailed. We are being let out 35-40 people at a time. We are given limited time to shower, make phone calls, use the kiosks and exercise. Certain officers purposely allow us out late and put us in early. This creates problems for us and between us as we try to stay in contact with family and friends and stay clean. I attempted to address this issue with the unit manager. I thought we had come to a solution. But an officer did exactly what we discussed shouldn’t happen in front of the unit manager. And the unit manager refused to do anything. Instead, he wrote a false misconduct against me to get me removed from the block. And it didn’t end there. The next day, my comrade was placed in solidarity for emailing people informing them of what happened to me. Their solution is simple: whoever is complaining, remove them. And it works to produce a chilling effect upon others.

I began to think about how we could approach this official tactic. What counter-tactic would work? One thing I learned, and Maroon wrote about this many years ago, is that we need to develop hydras and not dragons. There is only so much space in solitary. They cannot lock us all up. Moving together is always much more powerful than moving alone. The incident made me think about deep organizing and assessing just how much strength we have and how much actual support. The deeper the support, the more likely the success and defense against official repression.

Personally, I have a great support team. Their support enables me to keep going. This is why I stress connections across the walls. While I have faced repression here, they are beginning to understand that they cannot harm me without consequences. People care. People will agitate. The administration knows if we have support or not. That knowledge shapes their actions.

IA: So the struggle leads you back to study. How do you help others bring those two aspects of the work together?

SW: Generally, going into any study situation, my goal is to convey meaningful knowledge. I want people to learn things that will enable them to better understand the world and empower them to change it. Specifically, I do an assessment before determining what text we will study. I try to figure out what participants already know about certain topics. I try to understand the different ways participants learn. This can only happen if I build relationships with potential participants first. My point is that study circles need to be participant-focused. Often, facilitators focus on the syllabus and getting through the texts. The focus needs to be on those in the group and facilitating understanding and application. If we get through a text and the participants having extracted anything meaningful, something they can apply to their lives, I feel we haven’t succeeded.

Out there, you have to talk prisons up. Not so inside. Prison is our environment, our world. So everyone inside has an opinion about prisons and policing. I don’t have to create interest in these topics. It is already there. What I try to do is get people to see these issues differently. And many are willing to take another look. One good way to get started is by doing definitional work. Getting people to think about how they define certain terms is really about getting them to think about how they view the world. Two of our first definitions to explore are community and safety. How people define these terms is important. And often, we find that people change their definitions after study.

IA: How do you combat reactionary tendencies, patriarchal behavior, homophobia and transphobia, misogyny, anti-Blackness, ableism, and other forms of chauvinism and anti-solidarity thinking and behavior?

SW: Prison is a hyper masculine environment. Patriarchal thinking, sexism, homophobia, transphobia and ableism are rampant behind the walls. The only way to handle these oppressive behaviors is to confront them straight up when they manifest. I do so by questioning the person’s motive. We have sports teams inside. Often, teams are created through a draft process. The coaches often don’t know whom they are drafting until it’s over. During one volleyball season, a coach selected an openly queer prisoner. He didn’t know it until the first game. He didn’t start the prisoner until late in the first game. That is when he realized the queer prisoner was a great volleyball player. Players on his bench balked at playing with the queer prisoner and began to make homophobic comments. I walked over and asked them if they felt they were better players than him. They knew they weren’t. I asked them if they thought they would become gay if he played on the team with them. They vehemently denied this. So what is the problem? They were there to win a game. The best player on their team happened to be queer. So what. When confronted with their bigotry, most prisoners, being unable to defend it, pipe down. When enough of us do this, things will change. And they need to. Homophobia, transphobia, and ableism are prejudices that are still acceptable in our society.

IA: How have you navigated the guards?

SW: Most officers stay out of the way. They see us studying and leave us alone. They walk by and spy on us, but they don’t try to break us up. They allow us to pass out materials on the block. From the officer’s perspective, our studying is a good thing. We are quiet and less likely to get into trouble, especially the kind of trouble that would require more work from them. It is the upper administration that is antagonistic toward study groups. They see us building influence and they don’t like it. They are the ones who create obstacles to study, not the front line officers.

At Smithfield, we were able to do more because the administration actively recruited us to create positive outlets for prisoners. Fayette is very different. 180 degrees different. We do more work on our own. But I find that Fayette has created, through its oppressive acts, a hunger for knowledge among the prisoners. The organic desire is greater here.

IA: Why do you go through all of this, comrade?

SW: All I am doing is passing along the goodness that has been given to me to make the world better.

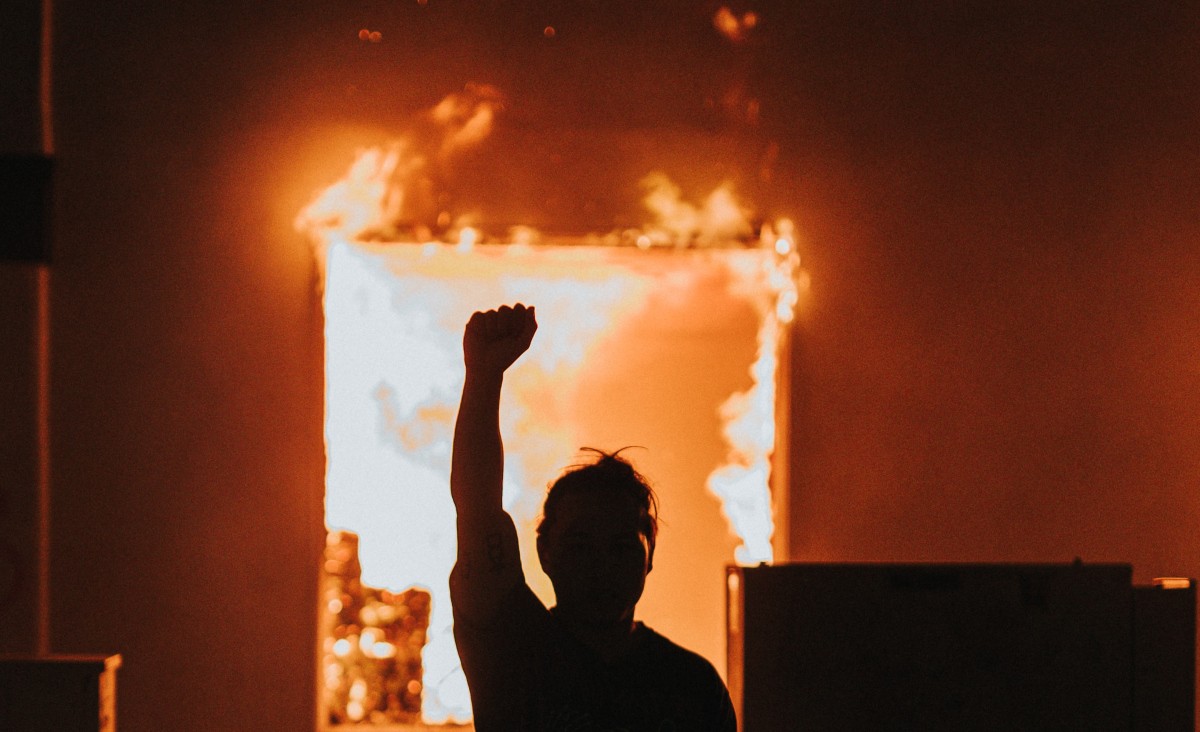

from It’s Going Down

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

On this episode of the It’s Going Down podcast, we speak with two members of Philadelphia Housing Action, about the ups and downs of 2020 that has been outlined in the recent piece, Occupy, Takeover: How Philadelphia Housing Action Turned Vacant Buildings Into Homes. It details how throughout 2020, members of the group moved unsheltered individuals and families into livable, unused homes owned by the Philadelphia Housing Authority. Moreover, in the midst of the rebellion that kicked off following the police murder of George Floyd, the group was also involved in setting up several encampments throughout the city, which often were marked by standoffs with the police and barricades in the streets.

While the eyes of the nation were centered squarely on the autonomous zone in Seattle, in Philadelphia, such encampments were able to leverage the city to turn over 75 homes to a land-trust, providing housing for multiple families and formerly unhoused individuals – including many who had been squatting in the months prior.

As extreme weather becomes the norm and building takeovers to provide shelter and resistance to sweeps of homeless camps become more widespread, the campaign by Philadelphia Housing Action remains an instructive example of what is possible.

More Info: Occupy, Takeover: How Philadelphia Housing Action Turned Vacant Buildings Into Homes, Philadelphia Housing Action on Twitter, and Philadelphia Housing Action homepage.

from It’s Going Down

Following months of riots, building barricades, and stand-offs with police trying to evict encampments, in late September of 2020, Philadelphia Housing Action was able to claim victory, after the city of Philadelphia offered unsheltered families and individuals access to housing in formerly vacant buildings, a process which people had already begun in the months prior, as homes owned by Philadelphia Housing Authority were squatted. In the end, upwards of 75 homes were handed over by the city, which included many homes which had been previously squatted. Here Philadelphia Housing Action looks back at 2020 with analysis and a timeline on what all went down.

On Sept. 26, housing activists and organizers from Philadelphia Housing Action declared victory after the city agreed to allow 50 previously unhoused families who took over a number of buildings to live in vacant, city-owned housing through a community land trust.

Philadelphia Housing Action has actually been many years in the making; grounded in struggles around gentrification, displacement, homelessness, police violence, institutionalization, family separation, legalized discrimination and more. All of us had been in the city for years if not our entire lives. OccupyPHA had been sweating the Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA) for over five years around it’s rogue private police force and systematic displacement of neighborhoods through forced relocations under threat of eviction, selling of public land to developers, deliberate vacancy and eminent domain. In 2019 OccupyPHA had an encampment in front of the housing authority which lasted over 120 days focusing on these issues that laid a lot of the groundwork for what was to come. The issue of vacant public housing blighting neighborhoods and creating the pretext for eminent domain had long been a concern and the idea of occupying those houses as an act of protest and counter-gentrification had been discussed for at least a year.

Early on in 2020, the group of us who would go on to form Philadelphia Housing Action were finding each other in the same spaces as we challenged the city’s Office of Homeless Services around the ongoing policy of evicting homeless encampments. Like most places, nobody seemed to give a shit about homeless people and attempts to get media coverage or rally allies fell pretty flat. After a while, it became obvious that fighting the city on their terms wasn’t enough, we needed to take direct actions and force the issue; moving people into vacant publicly-owned houses seemed like the best way forward. Once COVID-19 rolled in and people were given stay at home orders, it just seemed like common sense for us to move ahead with take-overs, like a few other groups had already done around the country.

For several months as a small group we worked at that entirely under the radar and managed to occupy around 10 Housing Authority houses, primarily with families numbering a total of 50 people before the city erupted over the murder of George Floyd. Although Philadelphia Housing Action represented members from several groups, there were never more than 5 or 6 of us doing the work, none of us were getting paid and we got all the houses up and running with less than $1,500 from small donations or out of pocket. We had no legal or formal organizational support and relied entirely upon ourselves.

SOURCE: Philadelphia Housing Action

Within 10 days of the George Floyd uprising, we initiated a homeless protest encampment downtown and within the month we had made the announcement about the housing take-overs. Over the course of the summer hundreds of people became engaged in the encampments and the campaign while our group grew smaller, some members breaking away and one dying tragically of an overdose. We ended the year having housed 150-200 people, occupying 30 houses, continuing to fight the city for what we were promised and doing our best to weather the drama that comes after any upswing in mass movement activity inevitably tapers off and devolves into finger-pointing and competition amongst former allies.

We are proud that not a single occupied house was evicted and that there were no arrests in the largest organized and public housing takeover in the United States in more than a generation. We are gladdened that through the protest encampments and occupations the connections between homelessness, housing, and institutional/historical racism were put into much sharper focus while the racialised systems of domination, surveillance and control that permeate the homeless industrial complex, public housing, family court and more were successfully linked to the movement against police and state violence. We are hopeful that our demonstrated ability to link, cross-pollinate and grow movements for tenants rights, homelessness, public housing and foreclosures can be replicated by others across the country, for indeed they share a common enemy. Our campaign victory to win the transfer of vacant city-owned property to a community land trust for low-income housing was a big win for the national movements around housing and human rights and was built upon the shoulders of the many people and movements who came before us both here in Philly and abroad.

It is our assessment that in the year to come, we will see a great deal more in the struggles around housing as a mass eviction wave looms and the economy seems poised to fall off a cliff. We hope that in some small measure, we have done our part to set the stage for the fights to come and inspire others to take the bold and direct actions necessary to keep our communities safe and advance the struggle for universal housing.

Below is an incomplete and summarized timeline of our activities in 2020.

January 6th Philadelphia Housing Action protests encampment eviction at 18th and Vine St/5th and Wood streets along with members of North Philly Food Not Bombs (NPFNB),

February 12 Philadelphia Housing Action attends and contests meeting held by Office of Homeless Services about the coming planned eviction of the encampment at the convention center,

March 23 Philadelphia Housing Action and allies including NPFNB contest eviction of encampment at the convention center on the morning of City’s stay at home order, confronts David Holloman of Homeless Services with newly published CDC guidelines advising against evicting encampments. Later in the afternoon, Philadelphia Housing Action takes its first abandoned PHA property and opens it to the homeless community.

Throughout April and May Philadelphia Housing Action identifies and opens 10 more city owned houses for homeless families while city remains in lockdown.

April 10-17th Philadelphia Housing Action supports first protests/daily actions since lockdown led by no215jails coalition for the mass release of people from jails and prisons.

April 16th Philadelphia Housing Action supports action by No215Jails Coalition at CJC, chases Judge Coyle and her small dog who had denied every single case for release put before her down the street and blocked her exit from the parking garage.

April 17th Philadelphia Housing Action publishes Op-Ed in the Philadelphia Inquirer calling for the opening of empty hotels and dorms for the unhoused during the pandemic.

April 22nd Philadelphia Housing Action / ACTUP informs the City of Philadelphia about federal funding available that would pay for non-congregant housing in the form of Covid Prevention Spaces.

May 5th Philadelphia Housing Action contests encampment sweep on Ionic St w/ members of NPFNB. Delays sweep.

May 13th Philadelphia Housing Action supports ACTUP, ADAPT/DIA, Put People First, DecarceratePA, Philadelphia Community Bail Fund and March on Harrisburg pressing Managing Director Brian Abernathy to open non-congregant housing for people living in shelters, nursing homes and recently released prisoners. Demands universal testing in all congregant housing.

May 27th City of Philadelphia evicts homeless encampment from the international terminal baggage claim. Philadelphia Housing Action had visited the encampment several times throughout may and participated in advocacy work that delayed eviction for over a week due to legal action from Homeless Advocacy Project and attention from the press. First Covid-19 Prevention Hotel is opened in Philadelphia.

May 30th Philadelphia Housing Action joins the largest multi-racial uprising against police violence in the history of the United States in response to the killing of George Floyd. Uprising is city-wide and spills into the surrounding area with a week of street fighting, looting, riots and marches. The National Guard is mobilized to the city and occupies downtown, displacing the homeless population while people continue to loot and blow ATMs.

May 31st Philadelphia Housing Action / ACTUP / Put People First / Global Women’s Strike / March on Harrisburg demonstrate/hold funeral services at the home of Liz Hersh, Managing Director of the Office of Homeless Services.

June 6th OccupyPHA and Philly for REAL Justice lead a march of several hundred from PHA Police Department Headquarters to Temple Police Department Headquarters and back highlighting the impact of unaccountable private police departments on North Philadelphia and their connection to gentrification and displacement.

June 10th Philadelphia Housing Action and homeless activists initiate a protest encampment at 22nd and Benjamin Franklin Parkway under the banner of Housing Now. Encampment defies police orders, declares a no cop zone, bans homeless outreach, issues demands and expands rapidly. In the evening a small march blocks traffic and breaches the outer doors of Mayor Kenney’s apartment complex.

June 15th James Talib Dean, 34, co-founder of the parkway encampment, co-founder of Workers Revolutionary Collective and member of Philadelphia Housing Action dies at his home of an accidental drug overdose. Parkway encampment officially renamed Camp JTD.

June 22nd Marsha Cohen, executive director of Homeless Advocacy Project issues a public apology for her comments to the Philadelphia Inquirer about Philadelphia Housing Action being ‘insane’ and ‘using homeless people as pawns,’ amongst other vaguely classist/racist comments.

June 22nd Occupy PHA/Philadelphia Housing Action makes public announcement about its housing takeovers on independent media outlet Unicorn Riot.

June 23rd Philadelphia Housing Action taps water fountain, runs 1000 feet of pip to install running water, hand wash stations and a shower at CampJTD.

June 26th Philadelphia Housing Action and representatives from Camp JTD meet with city officials in an abandoned storefront. City makes no offer of permanent housing, denies having power over the housing authority or ability to convey other vacant city-owned property.

June 28th Philadelphia Housing Action / OccupyPHA open second encampment on an empty lot across from Housing Authority headquarters on Ridge Ave. The lot, taken through eminent domain by the Housing Authority is slated for of 81 market rate and 17 ‘affordable’ units, along with a parking garage and ‘supermarket.’

June 30th Housing Authority attempts to fence in Ridge Ave encampment and post no trespassing signs. Encampment residents resist, blocking bulldozers and tearing fenceposts out the ground, led by Teddy Munson. Managing Director Abernathy orders Housing Authority to ‘stand down,’ proving that city has power over the Housing Authority. Supporters immediately erect barricades around the entire perimeter of Camp Teddy, working into the night.

July 7th Philadelphia Housing Action taps into city power at CampJTD, installs outlets to power fridges, etc.

July 9th Philadelphia Housing Action breaks off negotiations with the city after several weeks of talks. Cites city’s refusal to offer any actual housing and refusal to bring the Housing Authority to the table.

July 9th PHA Police attempt eviction of occupied house. OccupyPHA/Philadelphia Housing Action and loosely organized Eviction Defense Network rush to the scene and successfully force the police to withdraw before they can enter the building. The house is the first of only 4 to be discovered by the Housing Authority.

July 10th City posts eviction notices for both encampments, cutoff date set for July 17th.

July 13th Philadelphia Housing Action rallies hundreds of supporters at Camp JTD, vowing to resist eviction and demanding permanent housing. Support for the encampment ratchets up all week with allies calling for supporters to sleep over to defend the encampment the night before eviction.

July 13th-17th OccupyPHA and Camp Teddy residents protest at Philadelphia Housing Authority President/CEO Kelvin Jeremiah’s personal home every day.

July 15th City of Philadelphia pressures porta-potty rental company National Rentals to cancel contract with CampJTD. Philadelphia Housing Action supporters cut locks to city bathrooms at Von Colln Field in response.

July 16th City backs down from eviction. Managing Director Brian Abernathy resigns. Mayor Kenney says he will become personally involved in negotiations.

July 20th Philadelphia Housing Action meets in negotiation with Mayor Kenney, other high level city officials as well as the CEO/President of the Philadelphia Housing Authority, Kelvin Jeremiah. OccupyPHA vows to continue occupying houses. PHA carries out raid of long standing land occupation, the North Philadelphia Peace Park, in the middle of negotiations.

July 30th Final meeting with Mayor Kenney.

August 4th Both encampments weather Tropical Storm Isaias.

August 10th Philadelphia Housing Authority holds press event with employees posing as ‘community members’ speaking out against Camp Teddy. OccupyPHA and Camp Teddy residents counter-demonstrate, infiltrate event and get on the microphone.

August 11th Philadelphia Housing Authority announces the creation of a ‘Community Choice Registration Program’ in an effort to appear like it is meeting protest demands.

August 13th Deputy Managing Director Eva Gladstein breaks off negotiations with Philadelphia Housing Action in an email, saying protestors were not meeting the city halfway.

August 16th City posts 24 hour eviction notice for protest encampments.

August 17th Over 400 supporters turn out the morning of eviction to defend the encampments. City Council Members Gauthier and Brooks intervene and re-open talks between the city and the encampments Talks last for over 6 long hours. Lawyer Michael Huff files in Federal court for a restraining order and injunction against eviction, representing individuals from both encampments.

August 17th PHA Police attempt extrajudicial ejectment of occupied house late in the night. OccupyPHA arrives and forces PHA Police to leave mid-ejectment. OccupyPHA demonstrates at PHA CEO Kelvin Jeremiah’s home every day the rest of that week.

August 25th Federal judge rules in favor of the city, clearing the way for an eviction, but mandating 72 hours notice with protections and storage for residents property.

August 31st City issues ‘3rd and Final’ eviction notice set for September 9th.

September 1st Philadelphia Housing Action publishes Op-Ed in Philadelphia Inquirer detailing demand for the transfer of vacant city-owned properties to a land trust for permanent low-income housing. Philadelphia Housing Action meets again with the City despite eviction notice. City and Housing Authority finally admit to having the power to transfer properties to meet the demands, but claim they simply do not want to.

September 3rd Philadelphia Housing Action and encampment residents participate in blockading the reopening of eviction court. The courts are effectively closed down for the morning before protestors are cleared by riot police.

September 4th OccupyPHA and camp teddy occupy a many years vacant, but newly built PHA property around the corner from Camp Teddy. After holding the building for several hours, occupiers foolishly allow access to the PHA Police. PHA finally moves in tenants the same night. In an email, PHA informs OccupyPHA found Jen Bennetch they have requested a federal investigation of her and the housing takeovers under the Riot Act.

September 6th Philadelphia Housing Action, encampment residents and supporters rally and march to Mayor Kenney’s apartment building and hold intersection and rally for hours.

September 8th Whole Foods, Target and CVS board their windows in preparation of encampment eviction and possible riots. OccupyPHA and Camp Teddy visit the homes of senior managers of the Philadelphia Housing Authority.

September 9th In a repeat, roughly 600 supporters turn out to fight the eviction, barricades are massively expanded at Camp JTD, including the closure of N 22nd St next to the encampment. The street remains closed for the rest of the month. City attempts to send Clergy to both encampments in an attempt to persuade people to leave but they are shouted down and leave in humiliation. Although trash trucks and buses are staged on the parkway, police never appear. Both encampments remain in a state of heightened alert over the coming weeks. Police test response time and defenses several times but do not arrive in force.

September 10th supporting organizers at camp JTD invite Mayor Kenney to a brunch on September 14th, raise a banner facing the parkway with the invitation.

September 14th Mayor Kenney declines to attend brunch.

September 18th HUD Mid-Atlantic Regional Office formally confirms that the Philadelphia Housing Authority can legally transfer properties without the need for federal approval.

September 26th Philadelphia Housing Action announces that city has tentatively agreed to transferring 50 vacant houses to a community land trust in return for ending the encampments. City/PHA comments that the announcement of a deal is ‘entirely premature.’ In talks, City had confirmed with Philadelphia Housing Action that they were willing to transfer the houses and continue negotiations in exchange for removal of the 22nd st barricades, a decision ratified by popular assembly of Camp JTD residents after much canvassing and discussion over the next several days.

SOURCE: Twitter @PeoplesParty_US

October 1st Philadelphia Housing Authority proposes settlement with OccupyPHA for resolution of the Camp Teddy encampment. PHA offers 9 fully rehabbed houses, two empty lots, the transfer of any squats that have already been approved for disposition to the land trust, amnesty for all Philadelphia Housing Action squatters, an end to extrajudicial ejectments and evictions by PHA Police, jobs for encampment residents to rehab the houses, a 1 year moratorium on sales of PHA property and an independent study on the impact of PHA property sales, participation of PHA Police Department in City of Philadelphia reform initiatives and to fully implement the CCRP with up to 300 vacant properties.

October 2nd Camp Teddy residents ratify the agreement and OccupyPHA signs agreement to vacate by the night of Monday the 5th.

October 5th Camp Teddy vacates and clears encampment by deadline. PHA informs the City after the fact. City is reportedly furious.

October 8th OccupyPHA founder Jen Bennetch wins a PA Superior Court ruling setting a state precedent affirming the right to film DHS workers (Philly’s version of Child Protective Services) performing their duties. The case originated in 2019 when the Housing Authority and homeless service provider ProjectHOME brought a complaint against Ms Bennetch for having her children with her in the daytime during her 2019 124 day occupation of the PHA headquarters. Ms Bennetch denied DHS workers entry to her home and filmed them in front of her house. In the lower court ruling, the family court Judge Joseph Fernandes had ordered Ms Bennetch to delete and remove from social media all videos of the DHS workers and to never record them again. Ms Bennetch’s appeal to the Superior court was based on First Amendment grounds.

October 10th Managing Director Tumar Alexander approaches OccupyPHA with a ‘best and final’ offer for resolution of Camp JTD in exchange for 50 additional houses.

October 12th After multiple assemblies and extensive canvassing at Camp JTD, Philadelphia Housing Action signs agreement to vacate on a tight timeline in exchange for 50 additional houses. Over the coming weeks Philadelphia Housing Action, supporters, the Housing Authority and the City work to find people housing and clear the encampment.

October 21st A Camp JTD resident legally obtains a unit at the formerly occupied newly constructed vacant PHA property around the corner from Camp Teddy.

October 23rd Marsha Cohen officially resigns as executive director of Homeless Advocacy Project.

October 26th Camp JTD formally closes and is fenced in by the city. Upon closure Philadelphia Housing Action counted 30 occupied city-owned properties. In the final weeks, 35 residents were given rapid re-housing vouchers despite income requirements and 10 elders gained immediate access to PHA senior housing. Philadelphia Housing Action estimates that more than 200 people gained access to housing over the course of the encampment through housing occupations or various city/housing authority programs.

October 26th Philadelphia Police shoot and kill Walter Wallace Jr, sparking widespread riots.

October 29 November 1st OccupyPHA/Philadelphia Housing Action demonstrate nightly at Council President Darrell Clarke’s home forcing a meeting with OccupyPHA and allies on November 4th. The following week the Philadelphia Housing Authority confirms Clarke has dropped his opposition to Philadelphia Housing Action getting houses in North Philadelphia. By November 23rd Darrell Clarke procedurally kills his own initiative to give $14.5m to the Philadelphia Police Department and refuses to comment to the press.

November 11th Philadelphia Housing Action occupies lobby of 22nd district for several hours after receiving the MOU between Philadelphia Police Department and Temple Police Departments. MOU is read out loud clarifying the limits of Temple University Police jurisdiction and generally harassing the police working that night, a turkey was thrown across the lobby.

December 1st Philadelphia Housing Action visits Covid Prevention Site Hotels and occupies lobby, confronts security.

December 2nd Philadelphia Housing Action has call with Office of Homeless Services and hotel residents about impending closure of Covid Prevention Hotels on Dec 15th. Demands delay of closure and extension of program. Over the coming weeks it is revealed the city will be moving residents from the hotel into former halfway houses that do not have private rooms or bathrooms. Philadelphia Housing Action continues to organize with residents and other advocates for the permanent housing the city promised at the beginning of the program. Activity is ongoing.

December 23rd Philadelphia Housing Action successfully pressures PHA to get gas turned on to several properties that were being denied service by PGW. City moves first residents from prevention hotels to former halfway houses and Philadelphia Housing Action learns that the new facilities have no heat or hot water. Philadelphia Housing Action and supporters visit the home of Office of Homeless Services Director Liz Hersh at night, talking to neighbors and playing loud music to protest the closure of the Prevention Hotel and the placement of people with preexisting health conditions into congregant housing with no heat or hot water over the holiday.

December 28th Philadelphia Housing Action visits Walker Hall, the former halfway house owned by private prison contractor CoreCivic that is now housing residents from the Covid Prevention Hotels. Security denies access to the premises and calls the police. The location is in a remote industrial area and lacking services, transportation or access to food. Heat and Hot water are still not available to all residents, nor are they allowed to possess space heaters. Residents have windows in their doors and are not permitted to block them. Female residents complain about male guards looking into their rooms. No transportation was made available. Residents are searched upon entry and at least one resident, a disabled elder, has been expelled for possession of a marijuana cigarette.

January 1st Philadelphia Housing Action, pushing for corrections around the availability of federal funding in a Philadelphia Inquirer article on the closure of the Covid Prevention Hotels is able to confirm that the City of Philadelphia never applied to FEMA for funding that would pay 75% of the program costs of the program. The statement from a city official on record undermines the entire premise of closing the hotel due to a lack of funding and exposes a high level of willful incompetence at the Office of Homeless Services. Furthermore, Philadelphia Housing Action and ACTUP are able to confirm that the current facilities will not be eligible for FEMA funding due to their congregant nature.

from It’s Going Down

[This post only contains information relevant to Philadelphia and the surrounding area, to read the entire article follow the above link.]

Welcome to In Contempt, a new column based on the existing prison rebels birthday listing, but expanded into a more general look at repression and other relevant news from a prison abolitionist perspective. Here’s a few things that have been going on over the last month or so let’s dive in.

Everyone should support the defendants facing charges related to their alleged participation in the George Floyd uprising – this list of our imprisoned comrades needs to be getting shorter, not longer. The status of pre-trial defendants changes frequently, but to the best of my knowledge they currently include:

Lore-Elisabeth Blumenthal #70002-066

FDC Philadelphia

P.O. Box 562

Philadelphia, PA 19105

David Elmakayes #77782-066

FDC Philadelphia,

PO Box 562,

Philadelphia, PA 19105

Shawn Collins #69989-066

FDC Philadelphia,

PO Box 562,

Philadelphia, PA 19105

Steven Pennycooke #69988-066

FDC Philadelphia,

PO Box 562,

Philadelphia, PA 19105

When writing to pre-trial prisoners, do not write about their cases or say anything that you wouldn’t want to hear read out in court. If you have any updates, either about status changes meaning that people should be removed from this list, or about names that are missing and should be included, please reach out.

A few notable upcoming dates: there’s a call for mass clemency on Feb 1st as “national freedom day.” February 6th is observed as the international day of solidarity with Leonard Peltier. Further ahead, there’s a call for a day of actions focused on parole on April 3rd.

Deric Forney

A former Vaughn 17 defendant. While Deric was acquitted in court of all charges in relation to the uprising, he is facing continued retaliation, as he has been moved out of state to Pennsylvania, where many Vaughn defendants are being held on lockdown indefinitely (via placement on PA’s Restricted Release List) on vague and questionable grounds. Years after the uprising, these prisoners are still being abused for staying in solidarity with one another against the state.

Pennsylvania uses Connect Network/GTL, so you can contact him online by going to connectnetwork.com, selecting “Add a facility”, choosing “State: Pennsylvania, Facility: Pennsylvania Department of Corrections”, going into the “messaging” service, and then adding him as a contact by searching his name or “NS2698”.

Birthday: February 6

Address:

Smart Communications / PA DOC

Deric Forney – NS2698

SCI Coal Township

PO Box 33028

St. Petersburg, FL, 33733

Luis Sierra (Abdul-Haqq El-Qadeer)

A former Vaughn 17 defendant. While the state has now dropped its attempts to criminalize Abdul in relation to the uprising, Vaughn defendants continue to face retaliation. Abdul is also a contributor to “Live from the Trenches,” the Vaughn 17 zine.

Delaware appears not to have an inmate email system.

Birthday: February 19

Address:

Luis Sierra #00455723

James T. Vaughn Correctional Center

1181 Paddock Rd

Smyrna, DE 19977

from Dreaming Freedom Practicing Abolition

By Michael “Safear” Ness

(Written January 22, 2021)

The Pennsylvania Department of Corrections refuses to waste money on individual COVID-19 tests for the prisoner population, instead preferring to test each prison’s accumulated sewage for COVID levels.

An official PA DOC memo dated January 21, 2021 from Secretary of Corrections John E. Wetzel states, “Facilities will increase [prisoner cohort sizes] at different times, and in different amounts depending on their local infection rates, and the results of sewage testing.”

Recent sewage testing at SCI Fayette indicated increased COVID-19 levels, delaying an increase in prisoner cohort size until additional testing can be performed.

Prisoner cohorts, assigned groups for movement, are allegedly designed to limit the risk of exposure by reducing prisoner to prisoner contact. The theory is, if one person in the cohort is exposed to COVID-19, or tests positive, the entire cohort is quarantined to prevent spreading the virus.

In application, once a prisoner is exposed to, or tests positive for the virus, no other members of that cohort receive automatic COVID testing unless they register a fever. If a prisoner tests positive for the virus, their cellmate is not automatically tested, despite being forced to continue to live in close proximity to the infected person. Even if a prisoner is coughing or fatigued, they are not automatically tested.

By not testing these prisoners, the prison administration is allowed to keep the appearance of a low COVID-19 infection rate, choosing instead to test everyone’s feces collectively to see how many prisoners are actually sick.

from Instagram

FROM PHILLY TO MINSK – FUCK THE POLICE! Love to #foodnotbombsminsk ! They were arrested while serving, two days after they gave an interview where they spoke on anarchism and animal rights. Free them! Ay @fnb_minsk all love and solidarity ❤️????In other news-We made a good hot meal for our friends living outside, stirfry, pasta + sauce, apple bake, fruit salad and green salad. We also had a tent to give away and two sleeping bags ⛺️

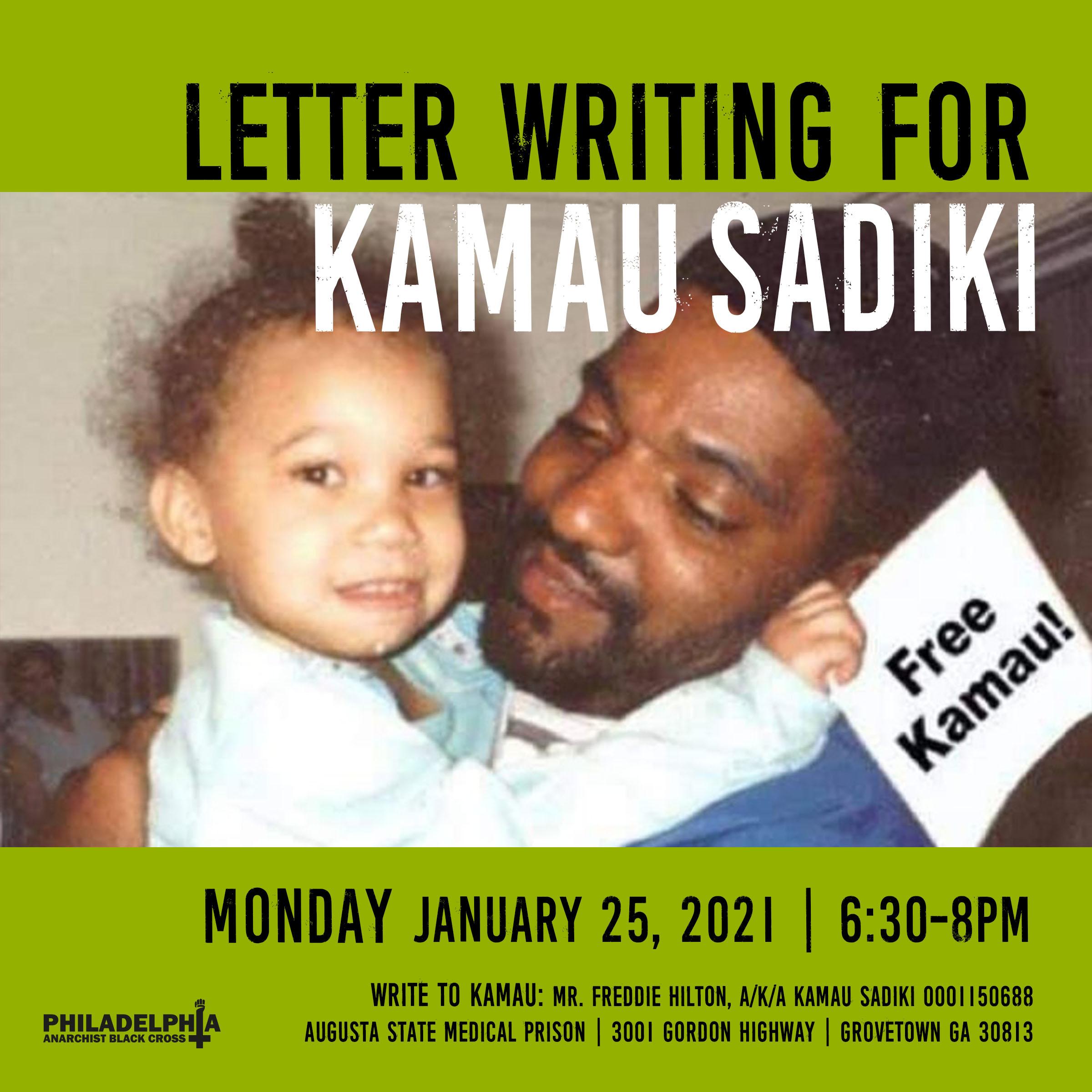

from Philly ABC

This month we are asking that folks write letters of support to former Black Panther, Kamau Sadiki. Kamau has been held in the Augusta State Medical Prison for years and suffered medical neglect. Right now, Kamau is in danger of needing his left foot amputated and needs to see a wound specialist. Before you join us next Monday to write a letter, please take a minute to tweet at @GovKemp & call the Augusta State Medical Prison at (706) 855-4700 to demand he be taken to the wound care clinic ASAP. At the letter-writing event, we will have an update about the medical campaign and send words of solidarity directly to Kamau so that he knows, and the prison knows, this situation is getting wider public attention.

This month we are asking that folks write letters of support to former Black Panther, Kamau Sadiki. Kamau has been held in the Augusta State Medical Prison for years and suffered medical neglect. Right now, Kamau is in danger of needing his left foot amputated and needs to see a wound specialist. Before you join us next Monday to write a letter, please take a minute to tweet at @GovKemp & call the Augusta State Medical Prison at (706) 855-4700 to demand he be taken to the wound care clinic ASAP. At the letter-writing event, we will have an update about the medical campaign and send words of solidarity directly to Kamau so that he knows, and the prison knows, this situation is getting wider public attention.

At age 17, Kamau dedicated his life to the service of his people working out of the Jamaica office of the Black Panther Party. Kamau worked in the Free Breakfast Program each morning and then went out into the community to sell the BPP newspaper later in the day. At nineteen, Kamau was a member of the Black Liberation Army (BLA). Several members of the BLA, including Kamau, left New York City and lived in the Atlanta area for a short period of time. On the night of November 3rd 1971, witnesses observed three black males run from a van where a police officer was murdered at a gas station in downtown Atlanta. The witnesses failed to identify Kamau from a photographic line-up and there was no physical evidence that implicated him. In 1971, the Atlanta police department closed the case as unsolved.

In 1999, the FBI in pursuit of collaboration in their attempts to recapture Assata Shakur (the mother of one of Kamau’s daughters), a political exile in Cuba, threatened him with life in prison if he did not assist them. When he did not comply, the FBI convinced Atlanta police to re-open the case and charge Kamau. He was arrested in 2002 in Brooklyn, New York some thirty-one years later after the murder. In 2003, he was sentenced to life imprisonment for murder and ten years to run consecutively for armed robbery. Much of his sentence has been spent in a medical prison because he suffers from Hepatitis C, Cirrhosis of the Liver, and Sarcoidosis. February 19th will be his 68th birthday so send him some birthday love as well!

This event will be held on Jitsi – we’ll post the meet link on social media the day of. You can also message us to get the link beforehand.

If you can’t join us on Monday, send him a message of hope and healing at:

Freddie Hilton #0001150688

Augusta State Medical Prison

3001 Gordon Highway

Grovetown, GA 30813

We also encourage sending birthday cards to political prisoners with February birthdays: Veronza Bowers (the 4th) and Oso Blanco (the 26th).

from Anathema

Volume 7 Issue 1 (PDF for reading 8.5 x 11)

Volume 7 Issue 1 (PDF for printing 11 x 17)

In this issue:

from Instagram

A second antifascist was visited by the FBI in Philadelphia yesterday. Well, sort of. The weird thing is the FBI wasn’t even looking in the right ‘state’ as the person they were seeking out lives in New Jersey. That’s some real Grade A police work! Anyway. The state is up to something – possibly in collaboration with far right conspiracy theories that ‘antifa’ had something to do with the right wing violence on January 6th. News flash: ‘antifa’ had nothing to do with that whole shitshow, that scene was a wholly white supremacist riot. Be safe friends, MAKE SECURITY CULTURE YOUR #1 PRIORITY. They are only trying to intimidate us – don’t let them – be brave!

from Twitter

If the FBI visits your home asking to identify far right perps in DC, remember you don’t have to answer any questions. Our networks say this is a pattern all over the country. You do not know what they’re actually looking for. Ask for their business card and contact us

Not in Philly? Contact your local anti repression network or a lawyer familiar with federal cases. Your lawyer will be able to contact them safely. Do not answer any questions without a lawyer present.

[Up Against The Law contact information:

(484) 758-0388

upagainsthelawlc@gmail.com

upagainstthelaw.org]

from Twitter

[This afternoon, January 15 2021, an anti-fascist comrade was visited by two FBI agents at their home in Philadelphia.

The agents said they had questions about the recent events at the Capitol. The comrade refused to answer questions & immediately got in touch with legal & anti-repression support. We don’t rely on the state to address fascist threats. The FBI has roots in repressing anarchist and Black liberation movements. We do not trust that they are only investigating the events at the Capitol. We challenge their attempts at repression with our collective refusal to speak to law enforcement.

If you are contacted by the FBI or other law enforcement, contact Up Against The Law or Philly Anti-Repression.

Up Against The Law: 484-758-0388

Philly Anti-Repression: 267-460-1886]