from Tubman-Brown Organization

By Bonny Wells

Right wing militias have been part of the US political landscape since at least the 1980s. The ideology that guides them, a combination of patriotism, capitalism, religious fervor, and white supremacy, has also been attributed to “lone wolf” attacks like the Oklahoma City bombing and the massacre in Waco, Texas (Kimmel and Ferber, 2000). There are more recent examples as well: In 2013, the town of Gilbertson, Pennsylvania was effectively seized by the police chief Mark Kessler, who also headed the Constitution Security Force[1]. In 2014, the armed standoff at the Bureau of Land Management by Cliven Bundy and his family put militias on the national stage again, as he was connected to the sovereign citizen movement and, by extension, the Oath Keepers Militia. Most recently, a standoff at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge from January 2nd-February 11th, 2016 returned the Bundy family to the public eye (Ammon Bundy was present at the Oregon Standoff). These movements are based on a particular narrative about control of land, which contributes to associated beliefs about the intrusiveness of the federal government and movements toward state sovereignty. While only one of the above incidents was directly carried out by a militia, the sentiments that inform right-wing militia activity undergird all of the conflicts: white settlers using any means necessary to control territory. At the same time, organizations on the political left have renewed their efforts to engage with right wing militias and find a common cause against the state. This paper will examine these efforts, as well as theoretical analyses of the position of white settlers, in order to assess these organizing efforts.

Understanding these narratives is useful at this moment in U.S. politics. In the months leading up to and following the election of Donald Trump, numerous articles[2] were written attempting to understand the mentality of the so-called “white working class”-rural, low income white people in areas that are economically depressed and have been neglected by politicians and institutions. Writers attributed Trump’s success to several factors, but racism and economic depression consistently topped the list[3]. In many cases, “economic anxiety” arguments were used to refute or complicate the notion that white rural voters were motivated by Trump’s racist, xenophobic and misogynistic platform. While responses to Trump’s election ranged from sympathetic to vindictive, they all pointed to the failure of existing institutions to redress economic exploitation and vulnerability. Neither major political party has the will nor the capacity to provide basic economic support for these people.

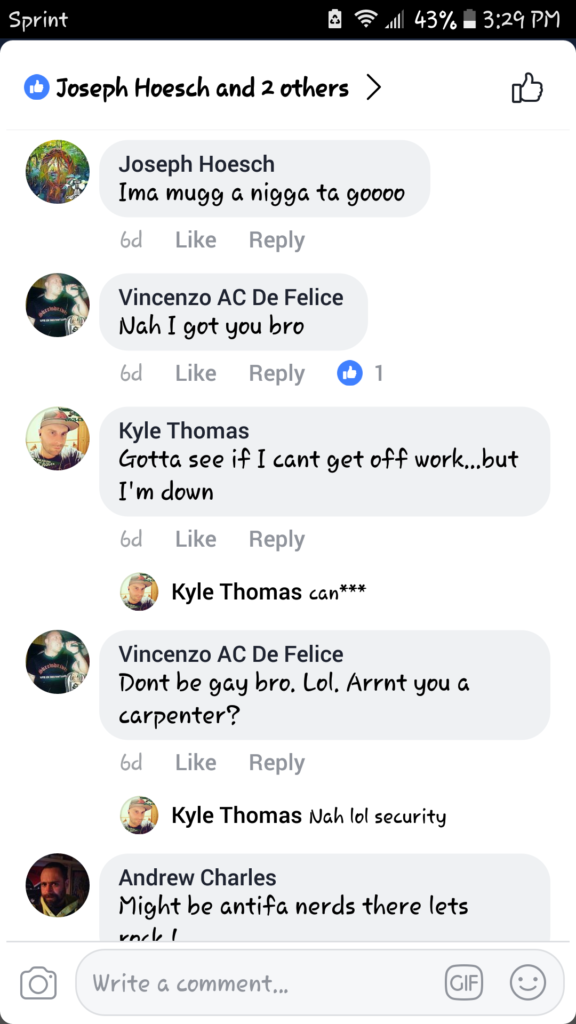

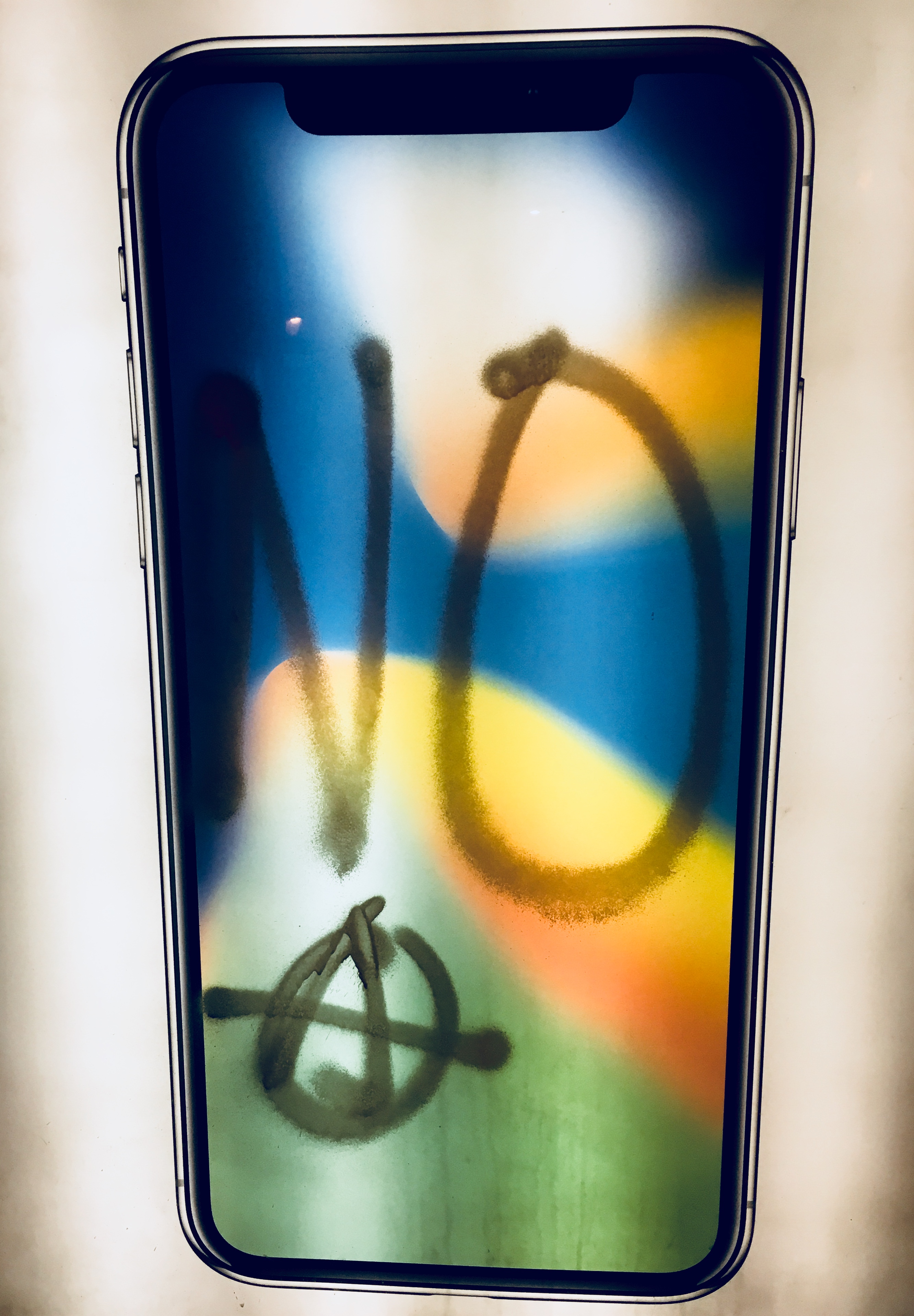

The framing of Trump voters as uniquely racist shifts the responsibility for white supremacy from white progressives, who prefer to see themselves as “good” or “antiracist” white people, to people comfortable with the most vulgar display of a set of values that is for the most part shared by white people across the political spectrum. This is further complicated by even more deeply assured white communists, socialists, and anarchists, who frequently deride white liberals for evading their role in white supremacy while insisting that the violent racial resentment of a prototypical Trump supporter would be best addressed by a combination of radical economic redistribution and stringent social conditioning (by which I refer to the militant “no platform”, direct physical confrontation approach favored by antifascist organizations).

A program of radical wealth redistribution is a significant improvement over liberals’ approach to racism as an individual attitude problem to be repaired through endless discussion and recognition, without any effort to address systematic racism or violent capitalist exploitation. However, anarchist and communist responses often fall short of directly confronting the white relationship to land and wealth in the United States. These tendencies argue that working class white people have been conditioned by wealthy white people to fight with working class people of color to fight for the scraps of unequally distributed wealth. In its less sophisticated forms, this argument states that poor white people have been manipulated by their wealthy counterparts to “work against their own class interests”-wealth redistribution that would benefit working people of all races equally.

Communists and anarchists have identified this political moment as an opportunity to radicalize poor white people and engage them in anti-capitalist and anti-racist activism. One such group is Redneck Revolt, a nationwide group formed specifically to bring poor white people to the radical left. Some chapters also form armed self-defense groups under the banner of the “John Brown Gun Club”. The objectives of Redneck Revolt are multifaceted[4], but a key component is the effort to converse with and educate poor white people and to offer an alternative to white nationalist groups, who have also consciously incorporated anti-capitalist rhetoric in their platform[5]. While they are one of the most notable examples, Redneck Revolt is part of a broader radical fascination with the aesthetics and popular culture of poor white people.

This type of organizing leads to strange bedfellows, or at least attempted alliances that other groups on the left might not consider. Recently, Redneck Revolt has been encouraged by the testimony of Peter, a former member of the III% militia who wrote a powerful reflective essay about a car ride that forced him to rethink some of his deeply held racist and Islamophobic prejudices. While Peter stated on no uncertain terms that he would not compromise his former militia members, his essay signaled that it is possible to encourage anti-racist and anti-capitalist consciousness in people who have been considered longtime enemies of the radical left[6].