Submission

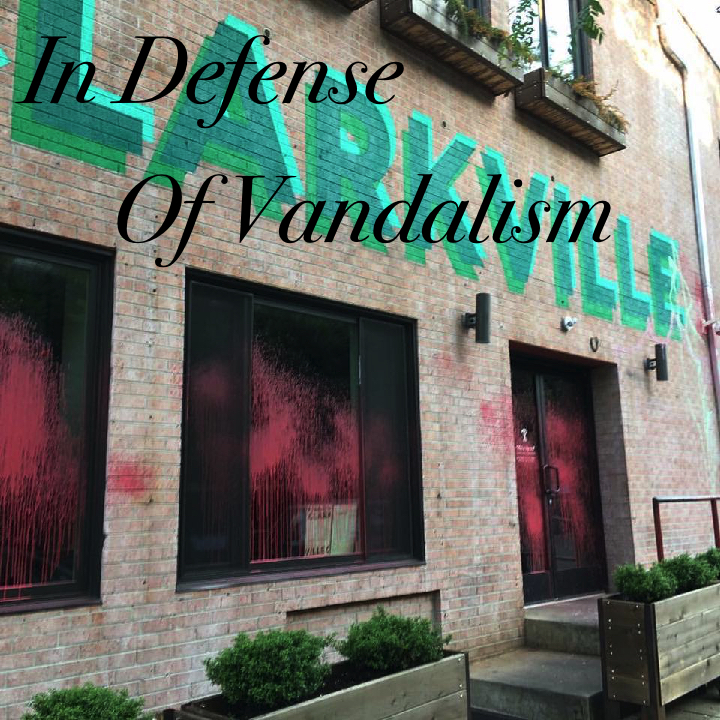

After the recent paint attack on Clarkville, a lot of criticism was directed at the vandals and their choice to vandalize the restaurant, and yet when looked at as part of a larger effort to stymie gentrification, vandalism is one of the only tactics currently being employed that materially affects the process in an unmediated way. Many of the critics have described the attack as juvenile, often simultaneously suggesting that dialogue, peaceful coexistence, long-term community organizing, and bureaucratic appeals are better and more effective ways of fighting. I’ll address the pitfalls of these approaches as well as the merits of vandalism as either a tactic or strategy.

A note on anti-gentrification: when talking about the struggle against gentrification, I mean the struggles to slow, stop, or reverse the encroachment of higher-end retailers and more expensive housing further into West Philly. This article comes from an anti-authoritarian perspective, after all, and I’m not interested in compromises with capitalists, be they multinational corporations or local business owners. I take for granted that gentrification should be addressed; I’m not going to engage perspectives that speculate whether or not gentrification should be confronted.

When dialogue is presented as an all encompassing strategy to end gentrification, I cannot help but imagine naivety on the part of its proponents. The processes that built Clarkville (for example) are systemic; there is not a single responsible individual that can be spoken to in order to clear up the problem of expensive dining in the area. Clarkville is a symptom of a larger problem, and that problem has tendrils in city government, NYC developers, UPenn, local business owners, and a myriad of other economic and political forces that shape and reshape Philadelphia.

That said, let’s assume for the sake of argument that either a single capitalist is responsible for the existence of Clarkville (or all higher-end restaurants in the neighborhood for that matter), or that there is a legion of willing individuals who have set aside time from work, school, family, and friends to speak with the various managers, realtors, owners, developers, politicians, etc that make Clarkville possible. Let’s also say, for the sake of argument, that the conversation(s) between these parties is both possible and agreed upon — now what? There’s no reason for someone interested in and relying on the expansion of a profitable economic venture (that in fact also acts as a stepping stone for an even more profitable economic venture) to simply stop after hearing that some concerned neighbors are upset that the economy won’t cater to them. Any such person is probably on their way to their boss’s office to get fired for wasting company time and losing company money if they have not been fired already. A dialogue might yield a small aesthetic change or something of the sort, but only in the interest of keeping the whole operation running smoothly. Even the beloved MLK has reminded us that power concedes nothing without a demand, which is to say without the possibility of a consequence beyond dialogue.

Class war: it isn’t my favorite term, but it is the phenomena that means that peaceful coexistence is not possible during gentrification. Class war is always already being waged (and will continue until class society itself is extinguished). It is the processes that keep the poor poor and allow the rich to continue accumulating wealth. Taxes, waged labor, rent, buying and selling commodities, and too many other mundane transactions and relations that make up daily life. Class war is the engine of the economy. For the sake of brevity, let’s stay focused on gentrification. It’s completely normal that the lower classes are continuously exploited, and this extends beyond the purely economic realm. Lower class culture itself is seen as a commodity to buy and sell; neighborhoods become attractive to people who would otherwise avoid them (business people, students, young professionals, etc), and the class war continues its rampage — this time via the physical dispossession of the poor by the middle class and the rich. When people call for the peaceful coexistence of the gentrifiers and the gentrified, they advocate resigning ourselves to the mechanisms of class war — the sometimes slow, sometimes fast removal of the poor through impersonal economic forces.

I do not have a lot to say about long-term community organizing other than that those who are willing to undergo it should be prepared to dig in their heels and hope for the best. That it is possible for large numbers of people to organize themselves and disrupt the economy that aims to push them out of neighborhoods I don’t doubt; whether it will happen or not is another question. Community organizing assumes a set of shared interests and commitments across a wide swath of people. I have little faith that such a group already exists and that, if one were to exist, that it would not just as quickly be divided and weakened by recuperation, repression, or the possibility of selling out. If anyone decides to attempt this long, arduous, and often fruitless path I wish them the best and hope they don’t condemn others who choose to struggle differently.

Legitimate channels exist for political and economic change; why not use those to escape our plight? Many have tried to make themselves heard through the democratic processes that surround development, neighborhood regulation, city planning and other spaces that surround gentrification, and they have achieved just that — they were heard. Their dissent was received, noted, and filed away with the rest of the meeting minutes. The assumption is that by participating in the various meetings, conversations, and public forums one can actually influence whether one’s neighborhood gentrifies or not. The reality of the matter is much more bleak; these channels are a safe way to funnel the frustration and creativity of various objectors into dead ends. These channels were never meant to prevent or even slow down the development taking place.

Vandalism, on the other hand, is always a direct and unmediated approach to dealing with gentrification. It can work as part of a larger strategy to bring attention to gentrification or put pressure on an establishment, or it can work on its own as a financial and often visual attack. From an anti-gentrification perspective, vandalism makes sense; if convincing a restaurant (in this case) to leave or completely overhaul its menu and demeanor to cater to a different clientele is not a feasible option and that restaurant’s very presence attracts the “right kind of people” to a neighborhood, why wouldn’t people opposed to gentrification take to simply doing as much damage as they can? A business that ends up costing more to keep clean and reputable than it can afford is bound to leave if enough people take the initiative.

There’s also something to be said about civility and how people are choosing to struggle. The most vocal critics of the painting of Clarkville have articulated other more civil and gentle ways of challenging gentrification (if they aren’t supporting gentrification). The notion that someone would want to literally fight against the expansion of higher-end businesses and expensive housing seems unimaginable to many. At this point, it should be obvious that at least some people have taken it upon themselves forgo civility in favor of hostility. Although the activist and leftist discourse about “fighting” against this or that injustice tends to refer to holding signs or meetings, it seems that some people have taken the word “fight” out of the quotation marks that usually surround it. Some people have nothing nice to say to gentrifiers, or anything to say to them at all; some people have forgone dialogue and begun expressing their contempt in more palpable ways. The honest expression of disgust and enmity behind such action is a real expression of how some people feel about gentrification.

For the more movement-oriented amongst the readers, it is possible for vandalism to fit nicely within a larger campaign against the arrival of the gentry. Although in the past there has been friction between the more and less civil actors* in the campaigns against the intensification of gentrification, it is possible for these two elements to more or less draw from each others tactics and energies. An act of vandalism draws attention to an issue that may otherwise pass under most people’s radars. Likewise, dialogue and social condemnation make targeted vandalism more understandable and more likely to be taken up by others and spread.

Whether as a solitary act or embedded within a larger context, every act of vandalism is costly. Vandals are bad for business, literally. Vandalism leaves an ugly scar on an establishment that is expensive to repair and expensive to ignore. When some place is vandalized, there are only two options for the owners: lose money cleaning and repairing, or lose business and reputation as the storefront sits covered in paint or shattered glass. Vandals hit where it hurts, right in the pocketbook. The process of gentrification is an economic one; it only makes sense that some would approach it on economic terms. This is what separates vandalism and other forms of attacking directly from other approaches: whether they are popular or unsupported, individually carried out or done by a group, they materially affect business in a way that cannot be ignored and always requires money in order to recover.

At the end of the day, regardless of the various qualms some may have with vandalism, it is no less a means of fighting gentrification. The painting of Clarkville is just another attempt by some to push out gentrification. No one person’s method will be perfect or the most effective, but vandalism certainly carries a directness and flair that other approaches have lacked. No other tactic has received nearly as much critique, not to mention insult. I’d love to see the same intensity of dialogue and critique that surrounds the attack on Clarkville accompany any and all forms of struggle against gentrification. A honest evaluation of all the tools and strategies available is the only way that the struggle can continue to adapt and develop. The possible strategies, tactics, and methods are only limited by one’s creativity and all of them should be scrutinized, refined, and continuously experimented with.

—

*In August of 2013 a group called the Point Breeze Organizing Committee was organizing a campaign against realtor and developer Ori Feibush and his company OCF Realty. As the campaign gained steam and PBOC prepared for a march through Point Breeze, the windows of an OCF cafe were smashed in the early morning preceding the march. PBOC failed to use the attention garnered by the attack to connect it with the neighborhood frustration surrounding Ori Feibush or to discuss his role in gentrification. The PBOC instead chose to not only condemn the smashing but also to vocally support a police investigation of the incident. If this isn’t throwing someone under the bus I do not know what is.

anyone feel like making a zine pdf?