from Tubman-Brown Organization

By Tubman-Brown

On November 2nd, Philadelphia Councilwoman Cindy Bass introduced legislation to further regulate corner stores and restaurants — specifically to introduce new restrictions and reinforce existing restrictions on these stores. The bill has passed through City Council and has now been signed by Mayor Jim Kenney as of December 20th. The contents of the bill can be viewed on the city’s website, here.

News about this bill has been circulating around the internet. The articles are generally condemning the Councilwoman’s bill as an unfair imposition on business owner’s rights to operate as they please. The Conservative Tribune claims, in an article called “Big City Dem Wants Bulletproof Glass Banned for Being Racist“, that the bill is evidence that: “We now live in a world where almost anyone and everything can and will be labelled ‘racist.’ Some store owners in Philadelphia are the latest victims of the PC police.” But the liberal majority in the city government agrees that the bill would improve quality of life in the city and passed it unanimously. We would like to criticize both of these positions and provide our own view from the perspective of poor Philadelphia, and use this example to draw attention to larger problems in American politics, particularly how the interests of the poor and working class are never represented. A better source for this story is Philadelphia’s The Inquirer, who published a more balanced article called “Barrier windows in Philly beer delis: Symbols of safety or distrust?” that tries to present both arguments and provides good testimony from some stores owners, but as a piece of reporting it does not look at the wider situation.

Councilwoman Bass is a liberal and a Democratic Party politician, and a black woman from North Philadelphia. She told Fox29 News: “We want to make sure that there isn’t this sort of indignity, in my opinion, to serving food through a Plexiglas only in certain neighborhoods.” This is in reference to the statements of Yale sociology professor, Dr. Elijah Anderson, who describes the presence of bulletproof plexiglass as a “symbol of distrust”, a suggestion that the customers are not “…civil, honest people.”

Bass’s statement is strange. Why would the plexiglass barrier make us indignant? Is it because it shows that we live “…only in certain neighborhoods”? Well, those “certain neighborhoods” are poor neighborhoods. If you live in a poor neighborhood you know it, and your problems definitely have a lot more to do with affording your groceries than whether or not the cashier selling you them is behind glass and wire. What Dr. Anderson of Yale fails to recognize, or does not say clearly enough, is that if the glass and wire is ugly it’s ugly because it reminds us of our own desperation and the desperation we are surrounded by. If it were not a symbol of the reality of poverty and violence it would not be troublesome. The trendy coffee shops and restaurants of University City and the recently deceased neighborhood of Fishtown are often decorated like warehouses and factories, with exposed piping, steel, and gritty lighting to create an urban atmosphere — the people eating there are not reminded of the reality of hard labor and poverty because it is not a reality to them, it is an aesthetic choice. Dr. Anderson and Councilwoman Bass equate the presence of bulletproof plexiglass with an aesthetic choice meant only to impart a message and ignore the circumstances that created it. The most important factor, regardless of whether the plexiglass is necessary or not, is finding out why it is there in the first place.

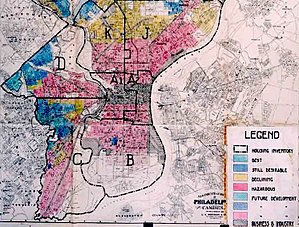

Poverty is violent. Most of the danger comes from the lack of jobs, healthcare, and education, but those threats sometimes spill over into robberies and shootings. Bulletproof glass is a sad reality in poor neighborhoods, a reminder of the interaction between one person robbing a store because they’re struggling and another person trying to run a little store. And these people running the stores are treated as the primary opposition to Councilwoman Bass’s bill. Bass claims that “…the bill has been mischaracterized by the people who run those stores – people who are exploiting a loophole in state law and hurting the neediest neighborhoods in Philadelphia.” The stores she is referring to are corner stores in poor neighborhoods in Philadelphia. These are redlined neighborhoods (Philadelphia is such a good example of redlining that a map of our extensive racial segregation is used for the Wikipedia picture describing redlining). In short, these are neighborhoods where there are none or fewer of the Wawas and Acmes and stores of similar reputation as are available in places like the Far Northeast, Chestnut Hill, or Center City. That’s because opening them in Strawberry Mansion, East Germantown, Kensington, and similar neighborhoods is considered a bad investment due to the high poverty and the crime that comes with that poverty. The owners of Acme and Wawa can afford higher rent in wealthier neighborhoods, or can place their stores strategically on the edges of poor areas.

An in depth understanding of the economics of the city, especially the relationship between the legal and illegal economics of the city, is necessary to understand the situation. The crime and poverty endured by the people of the city is usually explained away as a result of “poor morals”, inter-generational gaps in leadership, or simply stating or implying that the inferiority of black and brown people is the primary cause. These excuses that obscure the actual situation are common enough that we feel it is necessary to explain in detail these economic circumstances — economic circumstances not referring to simply the “state of poverty”, but the exchange of products, labor, profits, and power that determines who is poor.

This crime and poverty that makes much of the city bad for investment is there because the people living there don’t have money to spend to make it worth investing in. What results is a cycle of poverty, which is normally described as functioning something like: “to be poor is to be unprofitable and to be unprofitable is to be poor, and to be a criminal is one of the few routes available.” But this is wrong, because the poverty of some is very profitable to others, and the poor need to remain poor for that profit to be made.

Some activities deemed criminal, such as selling marijuana, are in themselves an easy and harmless additional income, and one that is genuinely appreciated by the community. But nonetheless due to its illegality it can only operate on a black market in which the wealthier sellers with the supply are rarely at risk, because despite the highly decentralized and casual nature of (local) marijuana trade, profit is still made primarily off of the poor sellers who risk the most and make the least, risking imprisonment and murder to sell a few ounces. This creates an illegal job market mirroring the legal job market, in which “street level” employees and working managers produce profit for the administrative bosses. It reproduces the legal business model, but without any of the labor laws regulating the treatment of employees, and an overt legitimization of violence in which an employee can be killed with no repercussions for something such as switching companies for a better wage. And, most importantly, this black market is in reality not separate from the free market of law-abiding citizens. The demand for the marijuana supplied by dealers comes from everywhere in the United States, all the suburbs, and small towns branching out from the cities, which far outnumber the inner city population. These suburbs and towns are largely white and policed more sparsely by state troopers or local police forces, police that are more forgiving of drug crime in a well tended suburb where they are respected among peers than in a city neighborhood where their interests are opposed to the interests of the community. Which is not to say that within these communities there is not police abuse or class struggle, as the difference between even a modest working suburb and a trailer park cannot be overstated, but instead to emphasize that the illegal economy of the drug trade is part of the economic fabric of even the most idyllic middle-class American suburb, those huge portions of the population that would like the right to use marijuana “responsibly.” These people reject its criminalization, often on the grounds that to only be available through criminal channels taints the otherwise innocent nature of marijuana. Here we see the worker who provides the marijuana as dehumanized and made equivalent to the process in which the product is received. The logic of the customer as more important than the worker (“the customer is always right”) informs our understanding of criminality, so that though both parties in a transaction are doing something illegal, the person providing the service is associated with the entire process of the drug trade, whereas the customer is associated only with the purchase. There are of course those opposed to the entire process of illegal drug trade, purchase, distribution, and consumption. They are merely the other side of the coin that advocate for legal responsible use. The condemnation and criminalization of the entire drug trade is just as much a part of the economy as is the purchasing of drugs by otherwise “law-abiding” citizens. The mass imprisonment of those involved in the drug trade — 46.3% of all US prisoners are in prison for nonviolent drug offenses — is incredibly profitable. That almost half of all prisoners are in prison for drug offenses means that half of the labor available to the prison system and the state is coming from communities much like those in Philadelphia where the illegal drug trade is a major employer allowing for people to survive — an illegal trade that is serving to supply all of America with their recreational drugs, not just the poor city folk, and a trade that is extremely profitable even for those who oppose it as it provides plenty of free labor, as is allowed under the 13th Amendment that bans slavery except in cases of punishment for a crime.

Though it is perhaps easier to see how the sale of marijuana does not justify enslavement, the same is certainly as true for genuinely harmful drugs. Most opiate users become addicted with legal pain medication and eventually need more than can be legally given to treat the same symptoms, creating a demand for the illegal sale of an addictive and dangerous substance that was, in most cases, originally prescribed legally by doctors — “nearly 80 percent of opioid users reported that their first regular opioid was a prescription pain reliever.” And this demand comes from outside these neighborhoods, from the mostly white and mostly wealthier suburbs who have the need and the money to spend on it, while the supply of opiates comes in through the ports of Philadelphia and Baltimore. This gives these poor city neighborhoods deprived of work and wealth a resource to sell and a market to sell it to. All of it is highly illegal, and of course the drug trade itself is operated by its own exploitative system of hierarchy, so that the people selling pills and heroin on the street and interacting with their customers are nearly always the most poor and desperate, and it is these poor desperate people who are punished with prison, felonies, or assault and death from competition in the drug trade.

This is the desperate context the question of plexiglass bulletproof windows needs to be considered within. And these must be the people ivy league professor Dr. Elijah Anderson is referring to when he says “of course some people are bad,” in his advocating for removing the glass, putting those “bad” people up against his “civil, honest people”, which would seem to suggest that his bad people are uncivilized and dishonest — just irrational criminals.

Because of these conditions, especially the cheap property and the high demand for groceries and convenience stores, the owners of the corner stores in question are very different demographically than the owners of any stores outside of poor city neighborhoods. They are overwhelmingly immigrants or children of immigrants — after all, we call them papi stores because so many of them are owned by Latino immigrants or members of Latino communities founded by immigrants. In other parts of the city, cornerstores and grocery stores are owned by black African immigrants, or Asian immigrants. Having considered this let’s return to the Councilwoman’s statement: “…the bill has been mischaracterized by the people who run those stores – people who are exploiting a loophole in state law and hurting the neediest neighborhoods in Philadelphia.” The only people who have expressed their discontent about this bill in the news have been a number of Asian operated stores who were asked to comment by The Inquirer after the bill had already been introduced.

Here there emerges the issue of inter-community exploitation among people of color, in the United States particularly the relationship between Asian immigrants and black Americans. This is itself a peculiar issue in the context of American liberal dialogue — the standard claim among up-to-date liberals and many true leftists is that racism is only possible with the presence of institutional power based on race, along with the insistence that white people are the only people with institutional power based on race. In most of the world it is true that, as a result of centuries of slavery, genocide, and colonial domination, whiteness is a major determinant of social rank and institutional power. But in places such as India, the Philippines, and much of Latin-America, (among many other places) that institutional power of whiteness is often exercised by people who are not white by American standards. Places such as mainland China also have their own racial chauvinism with its own exploitative systems of powers — which we do not claim whatsoever to be evidence that white supremacy is any less destructive or pervasive than it is, but rather to make sure we do not simplify the world into powerful whites and the unified, fragile non-whites who are without difference and conflict. The implication of stating, universally and without qualification, that only white people can exercise institutional racial power, is that the only power that matters is the power that is exercised by white people. It is the liberal White Man’s Burden, disguised as pity and guilt.

But, even acknowledging the real possibility that Asian immigrants could be exploiting poor black neighborhoods, we find that in the United States the primary issue remains white supremacy. Though some non-white immigrants may profit from that environment created by white supremacy they certainly are not doing so to any greater extent than a black cop or councilwoman, and in most cases have much less institutional sway than either of them, which is obvious considering that their main offenses seem to be selling alcohol and protecting themselves from gunfire. The poverty and redlined racial ghettos that allow Asian as well as Latin-American and African immigrants to set up and operate viable businesses at all, were created by and are maintained by white supremacy. Anybody who has set up a store in a neighborhood where robberies and shootings are so frequent that bulletproof plexiglass is worth investing in does not have a lot of money to begin with. The fact that the majority of those who were in touch with the press concerning this were Asian-Americans and Asian immigrants, who are generally wealthier than black and Latino people who also own an equivalent number of stores throughout the city’s neighborhoods, suggests that this is not limited to Asian run businesses and more likely due to black and Latino business owners’ hesitance to contact the press or the press’s failure to contact them.

Michelle Tran, who owns the Wayne Junction Deli on Windrim Avenue, said to The Inquirer: “I would love it if it were Center City, I could sell $8 burgers and $10 beers,” as opposed to $1.25 beers, said Tran. “But it’s a solid working-class neighborhood.” Mouy Chheng, the first to speak against, said her 19-year-old son was fatally shot by two armed robbers at the family’s South Philly convenience store in 2003 when it did not have a bullet-resistant window. Peter Ly, a West Philly beer deli owner who made news after he was shot three times in December 2011 when he went to deposit money at a Cheltenham bank, told Council of another incident a decade ago when he was shot six times during a gunpoint robbery at a beer deli he then owned on Lehigh Avenue in North Philadelphia with no bullet-resistant window. He has a partition in his current business. Bill Chow said a customer who claimed Chow shortchanged him threw bleach at him through an opening in the window even after he showed the man the surveillance video disproving his claim. Jeff Liu, owner of Kenny’s Seafood & Steak, put plexiglass up in his shop because a man he had asked to stop selling drugs outside of his store returned firing a rifle at cars parked outside. Also reported by The Inquirer: “Sae Kim, who owns Broad Deli on Broad Street near Susquehanna Avenue in North Philadelphia, said his business has been threatened numerous times but never robbed at gunpoint, crediting the bullet-resistant window as a deterrence…Before his family took over the business 20 years ago, the prior owner’s son was fatally shot when there was no partition. About 15 years ago, Kim said, a man with a knife tried to rape his mother-in-law but she was able to escape to safety behind the partition and lock the door.”

Councilwoman Cindy Bass and Dr. Elijah Anderson do not even acknowledge that the majority of these stores are owned by poor people of color, and in doing so ultimately avoid actually confronting the issue of white supremacy or poverty at all, instead trying to restrict the lives of the poor even further because some practical element that is part of our survival is also incidentally a reminder that surviving while impoverished is a struggle, a reminder that you live in “those neighborhoods.” Only someone who doesn’t live there could forget.

The Councilwoman’s dismissal of the detractors as “people…hurting the neediest neighborhoods in Philadelphia,” is particularly disgusting in light of the rampant gentrification that is exploiting the “neediest” areas, gentrification that is not only condoned but encouraged by the majority Democrat Philadelphia city government as a means of “developing” the city. It says enough that she takes issue with the owners of small, community cornerstores protecting themselves from the very real danger of gun violence, but does not object to encouraging the robbery and destruction of peoples homes that occurs when landlords sell entire blocks and apartment buildings to a condo baron like Allan Domb. Councilwoman Bass and her liberal friends are trying to beautify the city, and they’re framing it with progressive language. The conservatives against this bill, such as those in the Conservative Tribune mentioned above, think that by opposing such a restriction they are advocating for free business practices. What they don’t understand is that successful businesses, such as those run by Allan Domb, never advocate for free business practice unless that particular freedom interests them. Such as the tax abatement that real estate companies insisted be passed to help kick start their development. The city passed it under the guise that it would help homeowners, but the $690 dollars saved on your rowhome property tax doesn’t mean much at all when Allan Domb saves a million from it and buys your entire block to build a new apartment building for Temple University students. The freedom to take homes more effectively is something a successful business advocates. But the government run beautification of the city is also necessary to protect their investment and raise property values higher, and the further restriction of the lives of the poor, merchants or otherwise, is necessary for that. Successful businessmen don’t support free trade, they invest in the police that protect their trendy colonist tenants from the people who used to live there, the poor people trying to make a living on a market outside of government regulation and who are getting arrested and killed for it. The bulletproof plexiglass is one part of this supposed beautification process. The question of bulletproof plexiglass is not a question of business interests against progressive policies — they are one and the same, as businesses expect the city government to clean up the streets to make sure their investments are secure, and the city government is able to act as if it is concerned with the well being of the populace through strategic “reforms” such as this. (And individuals in the city government may very well be concerned with the well being of the populace, but as long as the city government is dependent on corporate development for their individual campaign funding and the wealth of the city, they will be acting against the health of the city.)

The rest of the bill includes a minimum of required seating and prohibits the sale of alcohol by dramatically heightening the requirements for a store to be considered a restaurant with grounds to claim a liquor license. This is again done under the guise of humanitarian concern for the people in these neighborhoods, with Councilwoman Bass saying, “Would you feel safe with an illegal liquor store next door to you, selling shots of cheap booze at 10 a.m. to loitering alcoholics?” Certainly alcoholism and harassment are a problem, but Bass completely neglects to mention that the social life of these communities often heavily involves these places. And those “loitering alcoholics” aren’t bogeymen, they’re members of that community, someone’s parent, someone’s child, someone’s friend. People hang outside the stores and talk and drink and listen to music and dance and flirt and argue. The culture of this social life often finds itself revolving around unhealthy coping mechanisms like alcoholism and lean. But removing the community coping mechanism does not solve the problem, it only kills the community social life and isolates its members, as has happened in the suburbs where each building and store is neatly sorted by its purpose, each family neatly sorted into their home, and each family member into their room. These people are not any healthier. Opiate addiction and suicide afflict suburbanites from various wealth brackets just as much as they affect the urban poor, but once you leave the city you will be hard pressed to find any kind of flourishing social life until you get to the trailer parks or the rare town that doesn’t exist only as the residential section of a stripmall. The suburbs and the wealthy neighborhoods in cities and rural areas might have better access to healthcare to treat addiction, as well as access to other potentially less destructive diversions that allow them to cope, but it is clear that the need to cope is just as present there as it is in the poor areas. And what about gentrification? Why do young middle class and wealthy people flee to cities en masse?

Gentrification has always been related to a fascination with and fetishization of poverty and ghettos. Genuineness, culture, and danger are all associated with the poor in a similar way they are associated with “primitive” tribes and peoples. But the genuineness and the culture isn’t some special feature of poverty — it is a result of people who are not tied so tightly to an exploitative economy of wage labor because they are barely allowed to participate in it at all. From the neglect, there is some space for creative human flourishing, real culture growing in the gaps of what is measured and regulated. Never in a suburb do multiple generations hang out on the street on a Friday night and yell and laugh with each other the way people do in the ghetto. Never do you see everyone pouring down the street celebrating a wedding or mourning a death. Of course, the conditions in those gaps of regulation aren’t something to be desired and everyone living in poverty wants out of it. But the wealthy and suburbanite mystifications of the social life of the poor shouldn’t stop the poor and the working class from realizing our unique position. The whole economic system of neoliberal capitalism depends entirely on our labor and obedience. But to have reliably cheap labor it needs to keep so much of the population on the margins of the world it creates — and from our place on the margins, we can see that another world is possible. Gentrification tries to reduce social life to a commodity, investors try to buy a community and find themselves with only sanitized neighborhoods and the same alienation in a different costume. Capitalist liberalism is the humanitarian face of this process, and its the face we see the most of in the government of cities. We should never forget, when we consider the city government’s intentions when it frames impositions on our social life as public service response to complaints, that in 1985 when the city bombed the MOVE house, they claimed it was a response to neighbors’ complaints about the smell of the compost and the announcements on the airhorn. Then the city government burnt those neighbors’ houses down and left them homeless. They burnt down a neighborhood by claiming that the specific, situational, and legitimate complaints of community members gave them the right to enforce a transcendent will of the city however they saw fit.

Liberalism can and should be leveraged for limited reforms. Prison reform and welfare expansions can be made for capitalism to sustain a believable humanitarian face, and can genuinely improve peoples’ lives. But ultimately it must always be insisted on that liberalism is dependent on the prison system, on poverty, and on the exploitation of workers. It is dependent on the reactionary attitudes it produces and is produced by, dependent on a cycle of false choices that serve the same interests. So stand up to save your neighborhood, fuck the city’s ruling elites, and burn down the establishments that only cater to the wealthy.