from Instagram

from Instagram

from Unicorn Riot

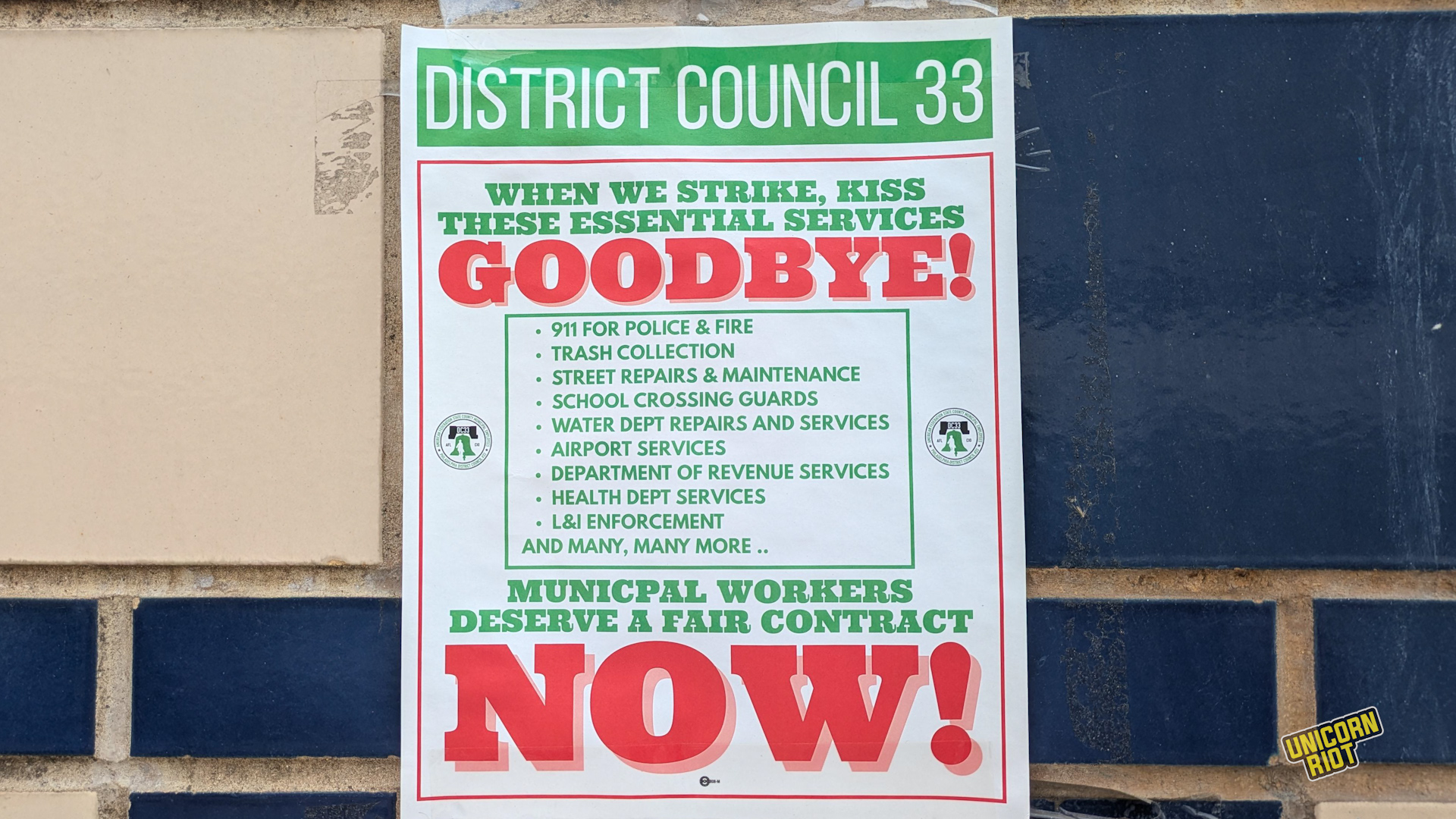

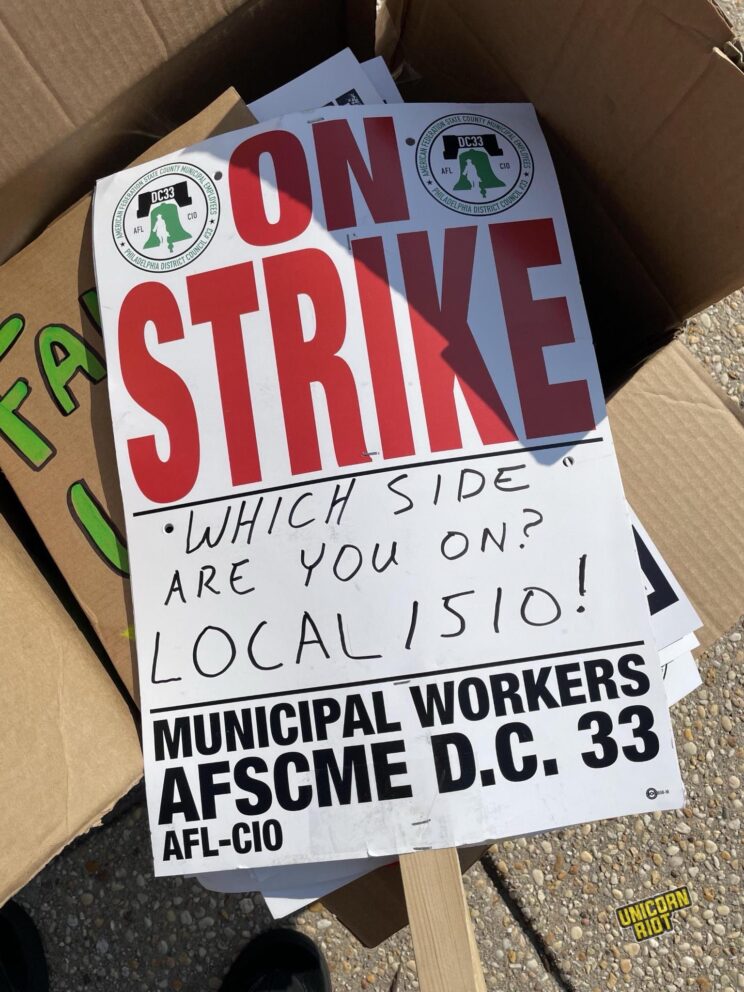

Philadelphia, PA — American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) District Council 33 (DC 33), the city’s largest blue-collar union, launched a historic strike earlier this month, halting sanitation services on a scale not seen since 1986. Despite the pro-union image Philadelphia Mayor Cherelle Parker wishes to project, legal injunctions were used to force many city employees back to work – creating pressure to end the strike.

“The city was trying to pick us apart with injunctions all over the place,” requiring water department employees, 911 dispatchers, and city medical examiners to return to work immediately, DC 33 President Greg Boulware explained in a recent interview.

After reports of alleged sabotage and confrontations with scabs (non-union workers hired to replace strikers), another court order demanded a stop to “unlawful activity” at picket lines, but included additional stipulations such as limiting pickets to 8 workers and requiring pickets to stay 10 feet away from entrances. With weaponized judicial pressure mounting, on the early morning of July 9, DC 33 reached a tentative three-year agreement with the city of Philadelphia that ended the eight-day strike.

“You can’t claim to be pro-labor, pro-union, pro-worker and then not make steps to do things that would change the economic status to do things,” said Boulware.

“The Mayor also tried to connect the housing initiative [a public benefit designed for ‘low-wage workers, under-employed or unemployed, municipal and union workers…’] to our membership, which had nothing to do with it at all. If you have a program in place try to get poor folks into housing, once they’re in that housing they have to afford to live in that housing…”

DC 33 President Greg Boulware

Sanitation workers in Philadelphia earn the lowest salary of any major city in the US. According to the MIT living wage calculator, the current average salary of a DC 33 member is more than $2,000 below the wage needed for a single adult without children to live in the city. For a family with one child, the living wage gap nearly doubles. One worker on the picket line said she couldn’t afford to buy diapers on her current salary. Depending on family size, the average city worker may be eligible for public assistance.

As garbage collection returns to its regular schedule this week, DC 33 members have until Sunday, July 20, to vote to accept the new agreement, or reject it – which may lead to a second strike authorization process. Many striking workers demanded no less than a 5% increase in their current pay, down from the 8% annual increase DC 33 initially proposed in negotiations. The tentative agreement only offers a 3% increase year-over-year, not far from the city’s original offer that led to the strike in the first place. The union vote will be announced on Monday, July 21.

Despite the anti-union tactics and lawfare by the city, many strikers stood true to their purpose of trying to win better economic treatment on the picket line. Unicorn Riot was able to speak with one DC 33 ‘Strike Captain,’ an unofficial point person informally designated by the union, about where things are potentially headed and how the strike went down. This interview was conducted on the condition of anonymity and represents their individual perspective and experience.

Unicorn Riot: How did DC 33 union members react to the announcement of the tentative agreement reached with Mayor Parker’s administration to end the strike, considering the terms were far below many of the strikers’ demands?

Anonymous DC 33 Worker: A lot of people are like, “What happened in there?” Because from a lot of picket lines it looked like we were doing OK. People could see the rotting trash getting worse and the understanding was that with more time, we had more leverage.

Even though people were missing paychecks, what I’ve heard from coworkers across the board is that if we were already striking, we should’ve waited longer. They don’t really understand what happened.

I don’t hear a lot of talk that [DC 33 President] Greg Boulware sold us out or anything. I have heard people say it’s suspicious that the AFSCME national President [Lee Saunders] sat down at the table with them the day that we folded.

I’ve heard that we should’ve struck for longer. People just don’t really understand how we went from guns blazing to folding immediately.

There’s a lot of questions about what a ‘No’ vote would look like. It’s hard, because the issue is that things are not really structurally coordinated, so even the idea that we would purposely try to track like, “OK, here’s our membership and let’s try to talk to everybody about whether they’re asking to vote ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ or just to get out the vote” is not intuitive, I’m finding, even though it’s like, to me, kind of what labor organizing is.

At this point, enough [DC 33 members] are individually pissed that the majority of the people who show up might vote ‘No.’ The majority of the people who show up probably won’t be a majority of the union. So if the issue is that people weren’t showing up to strike, having a majority of a minority vote ‘No’ doesn’t solve that problem. The way I’m talking about it with people is, you certainly should vote to show that people are engaged in the union on this.

I’m personally not in support of any kind of coordinated “Vote No” campaign unless it has an ask associated with it. If we wanna do a coordinated “vote ‘No’ until we see this very specific possibly winnable clause added,” then that would be one thing. But I’m wary of the idea of “just vote no,” because I think our leadership tried to get the best they could. Like, I do kind of believe that Greg Boulware got the best he could under the circumstances from where he was sitting and could see everything. So I hesitate to be like, yeah, vote no and that will suddenly mean we have all this leverage. If it wasn’t there, it wasn’t there.

There’s a lot of confusion and misunderstanding about what things trigger what actions. A lot of people saw the letter saying that the [DC 33] local Presidents, the executive board, had voted to send this Tentative Agreement to the membership. And they were like, “oh, do we not get to vote then?” And it’s like no, that’s who voted to end the strike, that’s not the vote [to ratify the tentative agreement].

UR: The tentative agreement (TA) isn’t ratified until you all vote, right?

DC 33 Worker: Yeah, but a lot of folks just saw that and thought, “oh, every local voted and so that’s done now.” So there’s a lot of talking to people about that. I’m not saying they don’t understand, but they are not receiving any information about how this stuff works.

UR: One thing that was somewhat unique about this strike was the amount of intersectional movement support that we don’t always see with Philly unions. For instance, the Sunrise Movement staging a sit-in at City Hall supporting the workers’ demands is not something we typically see in other municipal services or other strikes in Philadelphia. Why do you think that is?

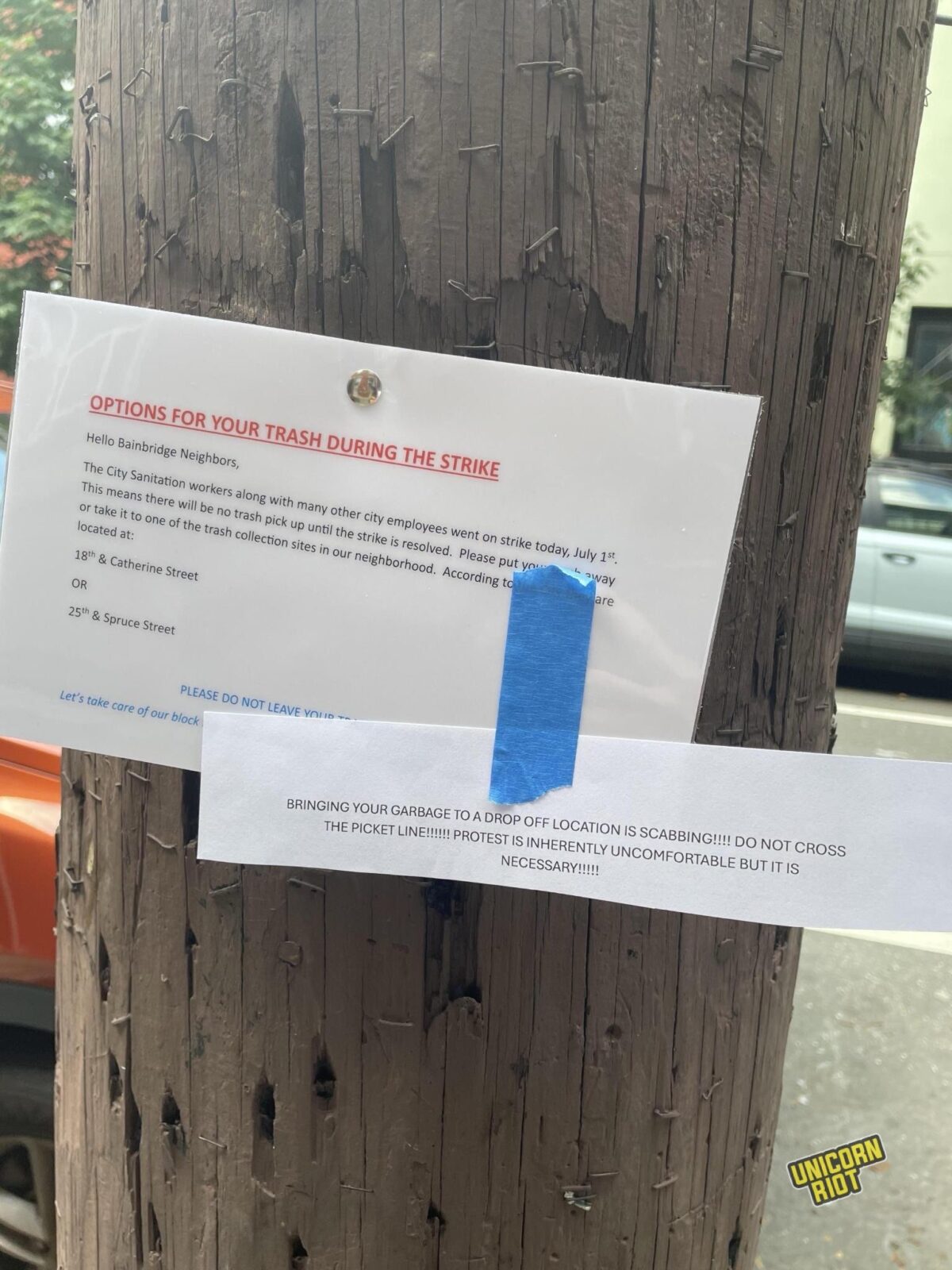

DC 33 Worker: Municipal strikes, and public sector strikes in general, depend upon public opinion. We could’ve done more with public opinion. Ideally there would’ve been more flyering, more encouraging people to co-worker-organize themselves by talking to their own social networks and getting their churches and community groups on board with the strike.

DC 33 Worker: I appreciate that community groups with less organic connections to us stepped up to do tactics that the union technically could not do. I can’t do certain behaviors without risking getting my own picket line and all the picket lines further injunctioned. But if the people of Philadelphia feel so inclined, then that’s their business.

UR: How do you see the DC 33 strike within the larger context of racial injustice, extreme poverty, and economic inequality in Philadelphia?

DC 33 Worker: One of the reasons we were able to come out with the force that we did – even while some chunks of the union did not have the same level of organization as others – is that historically DC 33 workers don’t make enough money to send their kids to college, and so the best jobs they can get are in DC 33, so there are these tight inter-generational networks within DC 33.

DC 33 Worker: It’s hard to live in Philly for more than a few years and not know somebody in DC 33, or be related to someone in DC 33 in some way. That’s one of the reasons there was such a staunch “we do not cross picket lines” feeling inside the union and in the city going into this.

I see a lot of people online saying, “oh, they folded because people are running out of money.” But people in a tough financial situation are often still sharp enough in their political development to understand when something is worth their while even if it’s going to cost something in the short term. I didn’t hear of anybody crossing [a picket line] because they were running out of money and thought that they financially needed to scab.

UR: Other than the injunctions and the city bringing in scabs (non-union workers) to do strikers’ jobs, what challenges did you see facing the strike?

DC 33 Worker: The biggest thing would be the chunk of [union] people who decided to stay home instead of show up and picket, we’re more concerned about that than people who potentially crossed [a picket line]. But that’s a question of, like, how do you build power in unions in between strikes? That was never gonna just come together.

UR: Moving forward, what you said about, if people decide to vote ‘No’ there should be a specific demand, what do you see happening? Does it sound like people would overwhelmingly vote ‘No,’ or does it sound mixed?

DC 33 Worker: I haven’t talked to anybody who is thrilled about this and wants to vote ‘Yes.’ I hear people who are not convinced a ‘No’ vote would do anything and so may not show up or may show up and vote ‘Yes’. I’m not hearing people who feel good about this or are excited about this.

DC 33 Worker: I don’t think – short of having a second historic strike – that we’re gonna come out with a drastically different contract than we have now, even with a ‘No’ vote. If there’s any internal organizing that happens, I would hope that it would be responsible about inoculating people about what is and isn’t possible from here, so that people don’t get even more disappointed with things. More than anything, we don’t want people to swear off union politics for good. That’s not going to get us the contract that we want next time.

So I’m concerned about that when people talk about ‘No’ campaigns. But when it comes to individuals voting, I’m gonna vote ‘No’ because I was very specific with myself and my coworkers about what our red lines were, what contract am I out here fighting for? I personally really wanted to see the lower wage classes abolished. Out of the things in our original proposal, that was something that was financially not that expensive to do and would have raised the bottom, which is what I was out there for.

DC 33 Worker: But I do think that long-term, that kind of “every individual decide to show up and vote if you want to” attitude is not gonna be sufficient for building rank-and-file power that can win a strike like this. I’m not confident that the number of people who show up and vote at all – ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ – will be any kind of majority of the union. If you get a minority of the union to show up and vote ‘No’ and that ‘No’ vote wins, that doesn’t mean that the power is there to execute a second strike.

There’s a good chance that the people who decide to show up in person to the union hall and vote at all will be the kind of people who want to vote ‘No.’ But I’m not sure what that will mean for the negotiation table that Greg Boulware and the [DC 33 Executive Board] will be returning to.

UR: Does a ‘No’ vote automatically mean the strike is back on?

DC 33 Worker: No. Just because there’s a ‘No’ vote, it doesn’t mean we go back on strike. Our strike vote that authorized the strike we just had is still in play. We wouldn’t have to re-authorize a strike. But just because we say no to this contract doesn’t automatically mean we will be on strike, in the same way that anytime they’re in the negotiating room, it doesn’t mean we are automatically on strike.

The union [leadership] would still have to authorize the second strike. [If they did], that forces everyone back to the negotiating table. And maybe the threat of striking again is something that’s in play. Certainly the membership would have a couple more paychecks to get us through – I’m at work right now getting paid – and by then I don’t think the entire backlog of problems on the streets, with all the streetlights out, will be cleaned up.

DC 33 Worker: So it’s not like we’ll be starting from scratch. It really depends on who shows up to vote, but if a low enough percentage of people show up to vote, that goes to show that people are probably not gonna be ready to strike a second time.

That’s all hypothetical. I personally think what will happen is a smaller percentage of the union will show up to vote, and those folks will be close to a ‘No’ if not definitely a ‘No.’ And that’ll be that and they’ll have to go back [to the table], but the leverage in that situation is a little unclear compared to the last time, other than the Mayor having the option to say, “OK, I have to give DC 33 something that the membership will ratify.” It’s not clear what those concessions would look like.

We might have gotten all that we can get. I personally think we could’ve struck longer and it would be a different situation.

UR: You said that DC 33 President Greg Boulware probably got the best deal possible given the circumstances. Philadelphia Mayor Cherelle Parker used the judiciary to essentially nullify workers’ right to strike by asking judges to order the water department and the 911 dispatchers back to work really quickly. And then after 8 days, bringing the sanitation workers back with an injunction, or the threat of it, seemed to act as leverage for the city to use to stop the strike, which is a pretty stark contrast to the last strike in 1986 where it took 20 days for the city to bring that injunction.

UR: Can the union use the law to defend the right to strike? It seemed like they were stuck between a rock and a hard place, overpowered by the local judiciary. Do you have any insight into all that?

DC 33 Worker:

I don’t think that there is a legal framework to have rebuffed those [injunctions] in the course they ended up in, but I don’t understand why they didn’t have more of a plan for preempting and responding to those injunctions when they happened.

It’s true that once we strike, the injunctions are coming. It’s also true that, well, it’s not like I show up to work having been injunctioned ready to pick up maggots off the street doing my best job with a historically gigantic backlog, you know. Even injunctioned workers can do work slowdowns. There’s still all these levers that are available. Even if certain people get injunctioned, there’s still plenty of ways to continue to strike. Most unions that strike at this point are not doing true work stoppage strikes the way that we did, so there is a whole playbook there.

I think the fact that they were not prepared with a game plan for those injunctions speaks to how ill-prepared they were to strike.

Given the circumstances, they maybe did get the best contract they could. But the circumstances were that they started planning for that strike a week before it happened. I know this as a rank-and-file member who was ready to step up and strike. I had been asking for six months, “can we please start making a plan for these pickets in case we need them?” and I did not get the go-ahead or the assignment that I even would be a strike captain, or where my location would be, until the Thursday before the Tuesday that we struck.

So if there’s a criticism of the union, I hesitate to locate it in the negotiation room. A lot of newer folks have found it really difficult to get any information or to participate at all. I’ve been really blocked in a lot of ways in my local.

I think it means something that the Presidents on the [DC 33 Executive Board] who did try to vote ‘No’ on this contract are the Presidents of the locals that have larger participation and have been planning for this for months and were ready to go last year when we almost struck. It’s not a coincidence that the [DC 33 local] Presidents who voted to stop the strike were the ones who didn’t prep for it in any meaningful way.

That’s why I feel that under the circumstances, it was an excellent strike for having been kinda seat of the pants. I’m not sure that they could’ve gotten more given the circumstances.

UR: I did see in an interview with DC 33 President Greg Boulware that he said the Water Department injunction came out like 30 seconds after the call to strike. It seemed that the Mayor’s administration was already prepared and aligned, coordinated with the local judiciary to get that out right away?

DC 33 Worker: Yeah, and [DC 33] should’ve internally had a contingency plan for that. When we started talking about striking a year ago, there should’ve been a plan for “OK, when the injunction happens, how do we behave?” If you had a base of strikers trying to strike, who understood how to respond to those situations that were basically inevitable (even in ’86 they did get an injunction eventually), you have to have a plan for what to do when that happens. It’s obvious that there’s gonna be some injunction at some point. The plan couldn’t have been to just fold as soon as it happened and let the Mayor dictate the timeline for that.

UR: Another union member shared an image from the city that seemed to say shouting at scabs wasn’t allowed, as part of the injunction?

DC 33 Worker: Yeah, I saw that image too. They sent it out, but I simply disagree, and luckily I am in a union. So if they try any kind of disciplinary action towards the strikers, I mean, I know a girl who threw a hot bowl of soup at her boss and she didn’t get fired. Obviously striking is different and there’s political reasons to come after us, but I’m pretty confident I’ll be OK.

DC 33 is really good at this 1980s to early 2000s union mindset of “holding onto what we’ve got.” That includes not letting anybody get fired – we will not let ANYONE get fired. They’re very good at holding onto shops that are organized, but they’re not necessarily noticing when things get contracted out to nonprofits or whatever.

That post-Reagan defensive mindset was necessary to survive the general dismantling of organized labor in this country. One new thing we’ve learned in the last months is that now there is energy for a more offensive approach.

UR: It seemed that, at least in the beginning, there were a lot of things outside the scope of what would be legally tolerated in a strike, people kind of pushing the envelope on their own, not under union guidance, working to hold the line at pickets in whatever way they could.

DC 33 Worker: Totally. And I think that’s a really beautiful thing about this strike. Even though it has gone the way it has gone, what we need in the labor movement is these big swings for the fences. And even if it means that when we threaten to strike next contract, both sides have a clear idea of what kind of power was available this time, there is something nice about knowing just what that looks like when we make decisions going forward. I hope that it doesn’t cause us to be more conservative in the future towards striking.

UR: There’s a lot of militancy in the origin story of the AFSCME chapter in Philadelphia starting with 222 and then eventually, after the huge garbage riots in 1938, DC 33 later became formalized. Do you see any parallels between past and present Philly garbage strikes?

DC 33 Worker: It’s complex. I wish it was a little bit simpler. I also wish that [union leadership] would’ve communicated to us that it was hitting the fan [in negotiations with the city] the night before it did.

There are plenty of escalations that members would’ve been willing to take on as it was hitting the fan, had they communicated that to us in any way. Not that we wanted them to come out and say “hey, it’s going really badly” and demoralize everybody. But there’s a way to say, “hey, here’s how it’s going in there, let’s ramp up a little.”

DC 33 Worker: This is my last thought about all this: when we had our strike captains meeting a couple weeks before the strike, they brought in a guy and they said this guy was working for DC 33 last time that we struck, in ’86, and he’s been holding out on retiring because he knows we’re due for a strike again.

He was so cool to hear from. It really did ground the whole room in what we were about to do. And if in the next 10 years they wanna strike again, they now have thousands and thousands of people who can play the role that that man played. The fact that people know what it’s like and know how to do it and know what brand of megaphone they wanna have and how to set up a tent in two minutes flat, that’s the kind of stuff that you only learn by doing it. That’s why I hope that this doesn’t cause a pendulum to swing where they’re much less likely to strike for another 50 years, because it’s so rare to have a union that has this many people with eight days’ strike experience.

He said something along the lines of, “I didn’t retire until this moment because I wanted to strike again” and that he had a positive experience of it. This meant we were all going into it not feeling like, “aw man, now we have to strike…” but rather, “hey, now is this moment that you get to exert power that you hold every day, but you very rarely get to make visible.” It amped people up that he had struck and had a positive attitude towards the idea of doing it again. I feel excited that there are now thousands of people who have that same experience.

from Instagram

Please join us in celebrating Local 8’s legacy of militant unionism and build connections with our local IWW branch.

**Date:** June 21st

**Time:** Noon

**Location:** Spruce Street Harbor Park

We must remember Local 8 and Ben Fletcher because he is a hero the Philadelphian working class created and his memory is still a threat to power, oppression, racism, and greed. As politicians and the owning class continue to ignore our needs and attack our right to organize, it’s important to understand the origins of racial segregation and systemic racism as part of the system that is still with us and that we must actively combat.

As an international, multi-racial, and gender inclusive union that has been around for over a hundred years, our struggle continues today. We organize workplaces to improve our material conditions and help others trying to build democracy in their workplaces too.

Let this historical marker stand as a commemoration to Fellow Workers, both past and present, and a reaffirmation of our need to organize as a working class to abolish the wage system. We reject electoral politics and vote begging as a means of improving our material conditions and instead, we recognize that the solution to our suffering lies with each other. We welcome all who want to organize and strengthen the labor movement, so we can grip industries through militant working class solidarity and win demands.

Thank you and shout out to @gemolteni for the poster designs!

from Making Worlds Books

How do we solve the housing crisis? Two L.A. Tenants Union co-founders wrote Abolish Rent to answer that question, guided by the expertise of LATU members, who are organizing to take back control of their housing, their neighborhoods, and their lives. At Making Worlds, we’ll bring together author Tracy Rosenthal and organizer and scholar Sterling Johnson to reflect on their struggles in their building and citywide, and talk about how our work right now shows us the future of the tenant movement, moderated by Max Fox and co-presented by Pinko Magazine.

Advance registration is appreciated.

SPEAKERS:

Tracy Rosenthal is a cofounder of the L.A. Tenants Union, a frequent contributor to the New Republic, and the author, with Leonardo Vilchis, of Abolish Rent, published by Haymarket Books. They organize with Writers Against the War on Gaza and are now on rent strike in New York City.

twitter & IG: @tracyrosenthal_

Max Fox is a writer, translator, and founding editor of Pinko Magazine.

Sterling Johnson is a doctoral candidate in Geography and Urban Studies at Temple University and organizes with Philadelphia Housing Action.

from Unicorn Riot

Philadelphia, PA — The unionized workforce that handles concessions at the South Philadelphia Sports Complex started to strike on Monday, September 23. Hundreds of Aramark stadium workers that bargain with the UNITE HERE Philly Local 274 union are demanding new contracts.

Unicorn Riot was told that Aramark, which is headquartered in Center City Philadelphia with a market capitalization value of $9.8 billion, has tried to prevent the unionized workers from qualifying for healthcare plans by dividing their hours between the three stadiums – Citizens Bank Park, Lincoln Financial Field and the Wells Fargo Center. (In a statement to NBC10 Aramark claimed it has now offered to count all stadium hours towards health coverage in a new contract.)

“Our contracts have all expired in all three buildings so we’re trying to consolidate the work. So, three different buildings doing the same job, you get different pay rates now. We want it to be the same pay rate. So if you’re a cook, a cook, a cook [at those locations] you get the same pay. It’s not like that. We want the hours to count from all three buildings to qualify people for health care. Right now they keep the hours separate.”

Kathy Hazel, Aramark concessions worker at Wells Fargo Center for 24+ years

“We might have worked all three buildings in a week, we still get one check from Aramark. But we get three different wages, that’s the issue here. […] They don’t want to agree to benefits like PTO. I understand it’s a ‘part time’ in one building, but when you’re in all three buildings you’re working like full time, you’re getting full time hours… but they’re still trying to treat us as if we are part time.”

Tarell ‘Doe’ Martin, Aramark concessions worker

On Sept. 24, outside a Phillies baseball game, union members called on fans to avoid purchasing food, drink and clothing inside the stadium, to pressure the company to negotiate a better deal. Aramark touts that “total income inclusive of wages and tips for this group of employees have risen 61% over the past five years,” while we heard from the workers that this is disingenuous because the tips have come from the public, not their employer. For an hourly cost of living increase, Aramark offered fifty cents a year, then another ten cents on top of that a year,

Many of the Aramark workers are not tipped at all, so they want to improve their base pay and benefits. “I noticed that they did not thank the Philadelphia fans for helping pay the salaries of their workers,” said picketing union member Kathy Hazel. “They don’t get any credit for any money I get from tips. […] There’s a lot of workers that are not tipped workers. And we’re here to support them, so that the hourly workers get an increase. They’re not getting tips, and we stick together.”

Down the street, independent vendors offered pretzels with notes on their carts saying that Aramark was on strike. Anthony Oliver with the striking Aramark workers pointed out that once again the ‘Counter Terrorism’ unit of the Philadelphia Police has turned up at Aramark labor protests. Forty-five Aramark workers were arrested in June by a force that included the same type of police we saw outside the recent presidential debate with ‘Counter Terrorism’ markings. Outside a Biden fundraiser last December, one officer on that team told Unicorn Riot that they are always deployed to protests but declined to name the specific policy which enables this.

UNITE HERE Philly Local 274 represents about 4000 private sector hotel and food service workers throughout the Philadelphia region, according to their website.

Prison labor is “remarkably common within the food system,” according to the Hunter College New York City Food Policy Center, and Aramark is at the heart of this game: it is notorious for its role in the food side of the prison-industrial complex. Its subsidiary Aramark Correctional Services provides services to hundreds of U.S. prisons and jails, privatized Immigration and Customs Enforcement jails operated by CoreCivic, along with contracts in at least 35 states, according to an investigation by American Friends Service Committee. It has long been notorious for substandard, contaminated and undercooked food.

Aramark investors benefit from prison labor used to prepare and package food in some prisons under the In2Work program. Students at Barnard College, New York University and Ireland’s Trinity College successfully got Aramark campus contracts cancelled. Georgetown University has been another site of pressure against Aramark both because of its prison labor and over on-campus workers’ contract in March.

In its corrections FAQ, Aramark says it’s in this business because “all people deserve healthy, nutritious meals.” A September 2023 Prison Journalism Project report by Justin Slavinski, “Meet the Company Getting Rich Off My Prison’s Awful Food,” described how the “100-or-so” residents in a Florida penitentiary who cook and clean are “wholly unpaid,” slashing Aramark’s labor costs to a small fraction of what legal employees would cost. Jail inmates have pushed for wages, and a prison strike protested Aramark.

This isn’t the only major political issue with the stadiums and sports construction in the city. The 76ers professional basketball team is seeking to move away from the Sports Complex and into Center City in 2031, by demolishing part of the Fashion District mall and building a $1.55 billion new sports arena site called “76Place” which is said to include 395 residential units.

This plan is opposed by many people involved with the Chinatown neighborhood a block away. “Save Chinatown” supporters argue that the 76Place project will displace and damage their neighborhood. Nonetheless, on September 18 first-term mayor Cherelle Parker announced her administration reached an agreement to move the Center City arena forward. On Sept. 25, the mayor announced more details in a community meeting, while further protests are expected.

Earlier this month, we heard from local activists trying to “ban artificial turf installation on city property including parks and recreation centers,” specifically in a huge set of proposed soccer fields at the large FDR Park which is directly west of the Sports Complex. (The FDR Park construction project has attracted opposition and protests since 2022.)

Another corporate giant in the city, Comcast, has its own designs on the Sports Complex. In February, Comcast Spectacor unveiled a $2.5 billion multi-phase master plan. Some observers suspect that Comcast will once again fleece the public coffers and obtain a development subsidy, like the tens of millions it obtained for the construction of their Center City skyscraper, along with tax breaks.

Philadelphia will be hosting six games at an upcoming FIFA World Cup in the Lincoln Financial Center, which runs during June-July 2026. FIFA scandals may have affected Philadelphia’s earlier bid in 2015. The push for this bid started in 2016. The city got up to $10 million in aid for the FIFA event from the state legislature via House Bill 1300 which was signed by Democratic Governor Josh Shapiro on December. In 2021 the city pitched using FDR Park for practice fields; however, as we heard at the PFAS protest, FIFA does not host World Cup games on artificial turf, so all 2026 matches will need to be on natural grass.

Coworkers, comrades, and fellow labor activists—wishing you a restful Labor Day weekend!

In keeping with our radical political traditions, we put our activist energies into May Day, not Labor Day. This doesn’t mean that we haven’t been craving a rest from the bone-aching grind of our labor. In our WSA branch, we are furniture movers, home workers, pink collar assistants, and healthcare workers. We all need a rest from exhaustion. This three day weekend is needed to recover.

Labor Day was fought for and won by workers. But we also know that this is far from enough. It’s a drop in the bucket.

Labor Day, with its parades and picnics, took the shape of a more capitalism-friendly alternative to the more radical May Day that was characterized by street protests and strikes.

While we focus our eyes on May Day, you will still see us with friends at local Labor Day events, re-affirming the community aspects of our work lives. We need to recuperate in preparation for amplifying workplace voices and building relationships. As we know, building relationships is the heart of organizing. So, strike up the grill. But tomorrow, we build the General Strike !

From Philly Metro WSA

“We are committed to building a future rooted in a classless and stateless society, where we, as working people, create workplace and community democracies that prioritize human needs over profits for the few. Our vision is a world free from the social oppressions of racism, sexism, and queerphobia. Through our revolutionary unions, we will transform the nature of work, paving the way to our collective liberation.”

From Greater Chicago WSA

from Making Worlds Books

Advance registration required. Please sign up here.

Please join us for a discussion of the Indian farmers’ protest, a movement that has created a worldwide audience and rekindled the hope for mass mobilization t to bring about progressive change in the agrarian sector in India. Farmers hailed victorious in December of 2020 after protesting at the borders of the national capital for more than a year, resisting three farm laws passed by the Indian government. The aesthetic and strategy this movement displayed was unique and captured the attention of media both nationally and globally. Mobile trolley homes, free medical camps, 24-hour langars (a Sikh tradition to provide free meals to everyone), libraries at every kilometer, film screenings, musical evenings, open discussion sessions were all part of the movement. People across caste, class, gender, region and religion boundaries participated in this resistance effort and the Indian diaspora played an important role in making this movement global.

The recent Indian farmers protest has been hailed as the largest peoples movement in the history of the country. After the right-wing BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party) government passed three pro-corporate farm laws, many farmers of Punjab camped out at the borders of the national capital for more than a year in protest. In solidarity with trade unions and workers, the farmers articulated various demands and successfully forced the government to rescind the laws in December 2021. This historic protest created a worldwide audience and rekindled the hope for mass movements to bring about meaningful change in the Indian agrarian sector. The protests have shined a light on the intersections between corporate agriculture in India and global capitalism. Crucially, women were at the forefront of the movement. Their involvement expanded the scope of the movement and brought questions of gender, patriarchy, and the caste system to the fore.

Navkiran Natt joined this movement from day one, witnessing and participating in all of the movement up-close. In this talk, she will share the story of this historic movement. Navkiran Natt is a student-youth activist and film/media researcher who works between Punjab and Delhi, India. She is trained as a dentist and later completed her Masters in Film Studies from Ambedkar University, Delhi. She works on transnational Panjabi migration and its reflections in Punjabi popular culture and media. Her primary areas of interest are media and politics, visual culture of new media, transnational migration, popular culture, caste and gender. She did a podcast series on the Green Revolution’s health implications in Punjab with the Goethe Institute, New Delhi. Currently, she is co-editor of Trolley Times, a newsletter that started from India’s ongoing farmers’ movement.

Event cosponsored by Philly Socialists and Philly DSA.

[March 18 7pm – 8:30pm at Making Worlds Books 410 South 45th Street]

from Philly IWW

We, the Philadelphia General Membership Branch of the Industrial Workers of the World, condemn the eventual closing of Hahnemann Hospital in Center City, Philadelphia, as well as the safety and environmental negligence that led to the explosion at the Energy Solutions Refinery in South Philadelphia on June 21st.

The assets of Hahnemann Hospital have been gradually stripped away by a private equity firm, which did not seek any improvements or reinvestments in the hospital. Patients in the United States continue to deal with private insurance companies that do not cover the total costs of their clients’ health care. Real estate developer Joel Freedman bought the hospital and has plans to sell the building for the development of high-cost real estate. Hahnemann Hospital provides care for many low-income and unhoused patients; these patients are to be moved to other area hospitals, which may burden and disrupt Philadelphia’s healthcare networks and the working class people they serve. Hahnemann employs doctors, nurses, cleaning staff, record keepers, security guards and other workers to maintain the hospital and provide care for patients; these workers will lose their jobs and livelihoods in the event of a closure. We support the efforts of unions such as the Pennsylvania Association of Staff Nurses and Allied Professionals, or PASNAP, along with other unions and supporters in taking action against the closing of the hospital. The Philadelphia GMB, however, is wary of politicians that promise to stop the closure, or who use the cause to strengthen their campaigns. This is only one of many hospital closures in urban and rural areas in the United States for similar reasons.

The explosion at the Energy Solutions refinery in Southwest Philadelphia was partially caused by the company’s neglect of basic safety and environmental standards. The company should compensate both the community members affected by the explosion and the hazardous chemicals that were released, and the workers who will be made jobless due to the destruction of the plant. The Philadelphia IWW GMB calls for the company to liquidate itself to pay for these damages, and rejects calls for the plant to return to the hazardous fossil fuel industry. The workers in these industries, including those who formerly worked for the Energy Solutions Refinery, should be retrained to work in less hazardous industries.

Both of these closures represent a glaring failure and the inability of the capitalist system to meet the needs of the people and workers. The price of healthcare necessities has risen unchecked and basic safety precautions in a potentially deadly plant are phased out as too costly, all while CEOs and the stock market make record profits. These are not isolated incidents: this is the logical outcome of a system that demands continuous growth. This system must be stopped and the workers themselves, not politicians or NGOs, are the only ones with the power to do so. We must organize now for the abolition of wage slavery and the preservation of what is left of our environment.

from It’s Going Down

In April, the union of teachers and staff at the Community College of Philadelphia won an important victory: a contract fighting off many of the years-long attacks from the administration.

Administrators had been pushing aggressively for higher workloads for teachers while at the same time attacking healthcare for all employees at the college. The Faculty and Staff Federation (AFT Local 2026) mobilized and pushed back, ultimately preparing for a strike. In response, the administration threatened to cut health insurance for all employees -an attack on the most vulnerable workers at the college and a transparent attempt to divide and conquer.

But the impending strike brought admins back to the table, and a new contract was signed. In the compromise that followed, the union won a workload reduction and the administration backed off a number of threatened healthcare cost increases, as well as agreeing to a pay increase for staff. But the union victory was partial. For example, Yusefa Smith notes in the union’s press release:

We didn’t win on class-size. I’m still teaching 36 students per class … At Montco and Bucks [other Philadelphia area community colleges], it’s 27-28 students per class. But we did win some workload reductions, which is a victory for our students. But we will keep fighting on class size.

The following is an interview with a union activist member of the full-time faculty at CCP. They wished to remain anonymous. We asked what lessons other campus workers can learn from the union struggle at CCP.

Can you summarize some of the important background regarding the recent CCP union struggle?

Sure thing. Before we get started, though, I should say upfront that I’m not an official union (or college) spokesperson, and the views I’m expressing here are solely my own.

Our union represents about 1,200 workers at Community College of Philadelphia and is composed of three bargaining units: the full-time faculty unit, the part-time and visiting lecturer faculty unit, and the classified employees unit, which includes many of the non-faculty workers at the college.

The collective bargaining agreement at CCP has historically been a pretty good one thanks to the work of our union going back to the 1970s. In recent years, the upper administration of the college and the board of trustees have sought to chip away at it. The most recent contract negotiations, which began around 2016, represented a continuation of that trend.

The college administration began negotiations by proposing that we accept several deeply concessionary proposals which would have negatively affected educational quality and made it more difficult to attract and retain a diverse faculty, among other things. The administration’s demands were wide-ranging and would have affected workload, joint governance, pay, and benefits. The admin basically wanted us to give up significant past victories in all those areas and more. The admin’s opening proposals would have meant some of the lowest paid workers at the college would have remained woefully underpaid. They also would have seriously undermined shared governance at the college, to the detriment of our students and everyone who works at the college. We were able to fend off many of these proposed changes but unfortunately not all of them.

In the last few years, teacher strikes have been kicking off, with an important rank-and-file power making itself felt within them. How do you see faculty/staff struggles at colleges fitting into that bigger picture of teacher strikes? What can we learn? Why is it important to struggle for worker rights on campuses?

This is a great and complex question, and I’m not sure I know the full answer. But there are some things I see in common when I look at labor action by education workers, whether they are early childhood educators, K-12, or higher ed workers.

First, I think it’s important to recognize that “education workers” means more than just teachers. At CCP our union represents faculty members, but it also represents the non-faculty workers who help the college run. This is one of the things I like best about our union.

Second, I think the struggles of education workers are inextricably tied up with the struggles of our students. We want schools that are good places to work and to teach, and our students deserve schools that are good places to learn.

Third, I think victories for education unions are important for the economy as a whole. Each one helps shape the labor market we all work in, and the labor market our students work in or will work in.

On a related note, I think the struggle we’re seeing between education workers and those who would try to control us is related to the question of the purpose of our schools. Are our schools going to be places where students learn the bare minimum of the basic skills they need to serve corporations and governments? Or are our schools going to be places where students are able to really develop themselves as whole people, meaningfully reflect on history and the present, and begin to develop solutions to the problems that are important to them? If it’s the latter (and I think the future health of our society depends on it being the latter), that’s going to take resources, and I think, unfortunately, it’s fallen to education workers, students, and community allies to have to fight for those resources.

I think the root cause of a lot of the strikes and other discontent I’m seeing among education workers is the result of government underinvestment in public education as a result of neoliberal austerity and the related rise of the notion that “schools should be run like businesses.” This is particularly salient and pernicious in institutions that are supposed to serve historically underserved populations.

I think the response is for education workers, students, parents, and community members to demand full and fair funding of all of our systems of public education. I would like to see education workers’ unions at the forefront of that.

What strategies did you see the administration using against the workers/union in recent months/years? What were some of the more effective ways campus workers responded?

Even people who had been at the college for a long time said this was the most inflexible and unreasonable they’ve seen a CCP administration be in negotiations. The administration’s tactics ranged from the sort of typical corporate anti-union crap you’d expect, to the sometimes bizarrely petty, to the really despicable threat they made to cut off the health insurance of everyone who went on strike.

The threat against the health insurance of anyone who went on strike I found especially odious. The administration made it against people who, in some cases, were making less than $15 an hour and who qualify for public assistance for food. We have union members who are on chemotherapy or who have family members on chemotherapy. We have members with high-risk pregnancies. We have members whose children have disabilities that require ongoing treatment. For the administration to threaten to suspend these people’s health insurance in retaliation for striking I found to be really disgraceful. I’m not sure what the college administration’s plan is now to try to come back from that and credibly claim to be leaders of the college, other than in an authoritarian way.

Our union’s response to this threat was to help our members understand how they could remain insured through COBRA or by purchasing their own health insurance. But I think this also underscores the importance to future labor struggle of universal government-provided health insurance.

For the years these negotiations were going on the administration spent I can only imagine how much of the college’s money on an outside law firm to represent and advise them. They also did strange things like order our union posters taken down from college bulletin boards. While we couldn’t outspend the administration on lawyers, since, you know, we were spending our own dues money instead of taxpayer and student dollars, the union does have a negotiations and strike fund and a lawyer of our own. As far as the posters being taken down: Well, there are more of us than there are of them, so we just put them back up.

The administration did other things, too. My understanding is that there was an agreement to keep the exact content of negotiation sessions mostly private, but the administration seemed to not fully abide by that. They’d cherry pick what they thought were the best parts of their proposals and put them out in public and email them to all the students. They’d use this to try to further their narrative that the union was being unreasonable. I think a good response to this for next time would be to have open bargaining.

Another thing the administration tried to do was to drive wedges between our bargaining units. Like I mentioned, two of our bargaining units represent faculty members, while the third one represents non-faculty workers at the college. I think the administration tried to take advantage of this in several ways. One thing they did was focus very intensely on proposals they had for increased workload for faculty. Faculty fought back against this, and I think the administration then tried to say, or at least imply, to the non-faculty workers something along the lines of, “See, the faculty are holding up your contract by fighting us over workload.” I can’t speak for everyone, but I think this sort of “divide and rule” tactic was pretty transparent, and in the end we stuck together and signed three contracts together, as we traditionally have. I think maintaining and increasing solidarity, communication, and camaraderie between and within the three bargaining units is going to be important for our union going forward. I think an important part of that is going to be committing to making our union a more actively anti-racist union, as there are different racial demographics in the different bargaining units.

What worked best in your struggle? What do you think were the most effective strategies and tactics?

I think the foundation of the most successful elements of our campaign were organizing conversations. These are conversations where union members volunteer to talk to other union members about what they’re thinking and feeling and what they’d like to see happen with our union. I think these are important for so many reasons. They build trust and relationships, and they allow union leadership to understand what members want in an in-depth way and make decisions accordingly.

Another important part of our effort was making it clear how what we were fighting for would be beneficial for students and the larger community. The Bargaining for the Common Good Network does a great job of describing this method of campaigning, and we used a lot from their framework in organizing our own efforts.

We received some political support from some members of state and local government, but when it came down to it, it was our demonstrated willingness to strike if needed that caused real change at the bargaining table.

What role did students play in the strike? How crucial are students as a support system for education workers struggling on a college campus?

From my perspective, students played a huge role.

First, on a personal note, I was deeply touched by how supportive my students were when I told them we might go on strike. I was worried they might see a potential strike as a betrayal on the part of their teachers, but almost none of my students seemed to think about it that way. Obviously, we all wanted to avoid a strike if we could, but my students were really clear that they’d be in support of me and the union if it came to a strike. I can’t fully describe how much that meant to me, just on a personal level.

Secondly, the possibility of a strike meant there was a lot of discussion on campus about strikes and unions. Some of this was between union members and students. Some of it was students talking to other students. Some of this was in class. Some of it was outside of class. But, all in all, I’d say the possibility of a strike led to a greater awareness among the students about unions and their power and importance. I remember one of my students saying something in one of our class discussions like, “Wait, so you can just say ‘no’ to what your bosses want to do? We gotta get a union at my work.”

Some students became actively involved in support of our contract campaign, contacting local politicians, the college president, and the college board of trustees. Some showed up at our demonstrations. Some talked about running for student government and trying to address the same issues with the college that the union wants addressed regarding things like funding, resources for students, and class sizes. It was really inspiring and touching for me to see our students become aware and active around these issues like many of them did. I think this may have been one of the best aspects of the contract campaign for me.

What main lessons do you think other education workers struggling in Philly and beyond could learn from what’s been happening at CCP recently?

So much happened. I think I am still processing and learning from everything that happened. But right now, these are the things that stand out as lessons I learned:

The importance of ongoing one-on-one organizing conversations between members as an organizing strategy that builds solidarity, camaradiere, and communication.

The importance of using a Bargaining For The Common Good framework where the union makes clear how what the union is fighting for will benefit the greater community. In our case, this was things like fighting for full funding for the college, smaller class sizes, more resources for students, and a more diverse faculty at the college.

Start organizing and preparing to strike early. Like years early. Our current contract ends in three years, and we have already begun our campaign for the next one.

Don’t underestimate how much work it is. I didn’t formally count, but I am sure our contract campaign required literally thousands of work hours.

At least in our situation, the negotiating at the bargaining table seemed to be more about power than debate. It didn’t seem to really matter whether we had reason, logic, evidence, and well-crafted arguments for our proposals. It seemed to come down to whether we could demonstrate enough power to force the other side to have to change their position. As an academic observing negotiations at an academic institution, I found this particularly disappointing, but I guess here we are in late capitalism.

Political allies are nice, but it’s the threat of a strike that is the source of your power.

I hope this is all helpful information.

from Facebook

from Anarchadelphia

I’m curious why I don’t see more outright solidarity from the self-proclaimed “reds” in the city with local striking workers. I’ve seen them attending every possible kind of demonstration, but never supporting strikes (like some west coast anarchists have done in recent years in the ports), taking actions against scab sites and employers (like some of the union members with some sort of teeth), or reaching out to the frustrated at more reformist rallies (the way the insurrecto-oriented have been doing against prisons and the police, locally).

I don’t find any promise in the possibility of the (ever-dwindling) working class uniting and rising up to overthrow anyone, let alone even pursuing a non-hierarchal society —and even if I did, I don’t believe unions would be the medium to achieve this. But, red anarchists purport to believe just that, suggesting it would be in their interest to participate in such a way. Yet, they seem more likely to be organizing with college kids and liberals at a $15 & a union rally — or so it seems to me.

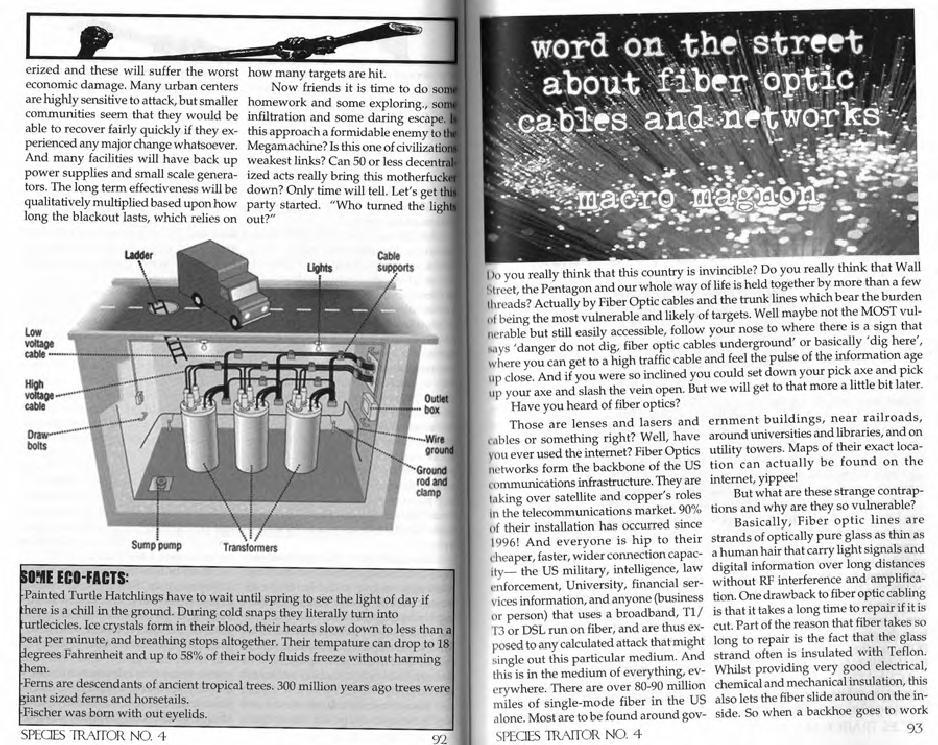

This crosses my mind with the passing of May Day, as I remember picketing workers infiltrating a car show and trashing it at the convention center, as I watch the CWA striking against verizon again, and further reports of sabotage unsanctioned by said union against Verizon’s fiber optic infrastructure circulate. Whether the CWA does not, in fact, condone the sabotage or is trying to keep its hands clean begins to illustrate its limitations, and the complete absence of radical unions like the IWW from anything substantial since the first red scare illustrates theirs. The last local news of note we’ve had from the IWW, in fact, includes an absolute failure around organizing a South Street Workers’ Strike (was that in the ’90’s?), to scandals resulting in the booting of certain “esteemed” local anarchists over financial discrepancies, to an article in support of striking Santander Bank employees in Spain. This is hardly the stuff of a restless, growing, anticapitalist mass.

The Prison General Strike this September, as called for by some Texan prisoner wobblies, could bring about the first functional endeavor of the IWW in almost a century, however, and I’m excited to see it happen. Maybe this is the long overdue tactical transition the reds have been searching for in response to the recuperation of workers as increasingly comfortable consumers?

I would love to be proven wrong in such a way. I don’t agree with many red anarchist goals or tactics, but please make a go of it and prove me wrong; show me why these things are a good idea. Don’t tell me, I cut my anarchist teeth on Berkman and Goldman and abandoned a union that proved useless to my needs, but try to make these things happen if that’s what you actually believe in.

And sometimes I wonder what it would look like for such ideas to come to fruition. For red anarchists acting in kind with striking workers against fiber optics developing a temporary, tangible, action-oriented affinity with green anarchists, for instance. What other avenues might we find intersections on?