from The Tubman-Brown Organization

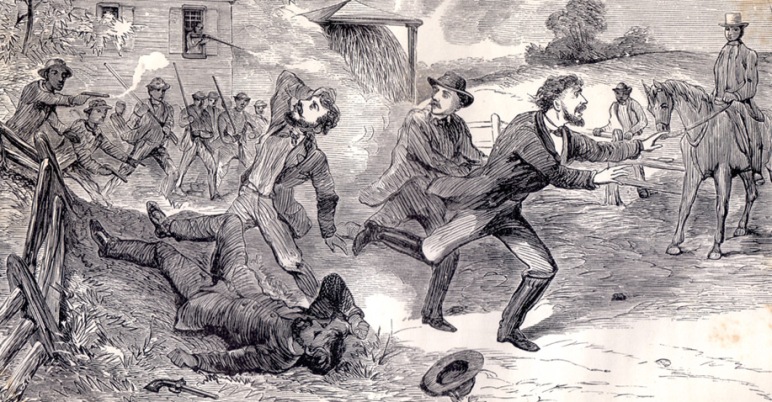

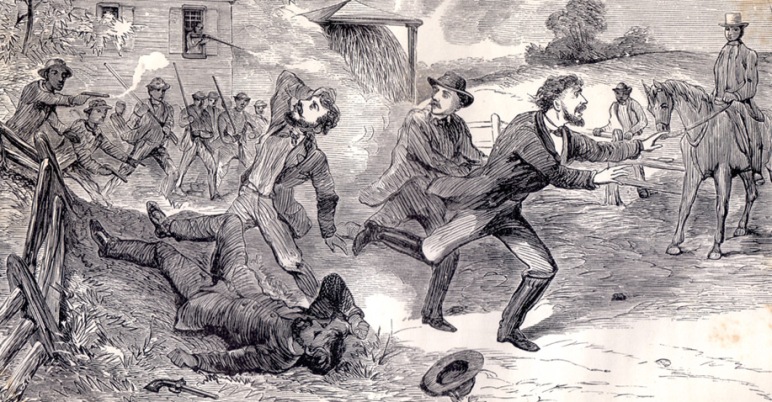

[The above image is a depiction of the 1851 Christiana Riot, near Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where a slave-owner was shot and killed when attempting to retrieve an alleged “fugitive slave.” The subsequent trial took place in Philadelphia.]

By Arturo Castillon

Edited by Madeleine Salvatore

I ask no monuments, proud and high,

To arrest the gaze of the passers-by;

All that my yearning spirit craves,

Is bury me not in a land of slaves.

“Bury Me in a Free Land,” Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

In the 1850s, the author of the above poem, Frances Harper, was part of a network of revolutionaries who made it their mission to abolish slavery in the United States. Known as Abolitionists, these partisans of freedom fought for the immediate emancipation of slaves, and developed a specific approach to Abolitionism known at as “immediatism.”[1] In the 1820s, the most radical Abolitionists in England and the United States began using this term, “immediatism,” to distinguish their strategy for abolition from the predominant, gradualist one.[2]

The Abolitionists that we are most familiar with today—Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, and John Brown—all fought for the immediate emancipation of slaves, a prospect that most people at the time, even most abolitionists, considered extreme and impractical. Yet, in the long term, the immediatist tendency proved to be the most practical and strategic. Instead of miring themselves in legislative strategies or insular sects, the immediatists built organizations to secretly assist thousands of people fleeing from slavery, who in taking the risk of freedom, deprived the southern planters of their primary source of labor—slave labor.

In Philadelphia, black abolitionists like Frances Harper, William Still, and Robert Purvis would rise to the forefront of the immediatist struggle against slavery. Because of the city’s proximity to the South, it was a crucial junction point on the Underground Railroad, a secret network of routes and safe houses that people followed northward when fleeing from slavery. Undeterred by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which legally guaranteed a slaveholder’s right to recover an escaped slave, hundreds of escapees made their way to Philadelphia every year, most coming from nearby Virginia and Maryland. With the Compromise of 1850, the Southern slaveholders strengthened the Fugitive Slave Act, which now required the governments and citizens of free states, like Pennsylvania, to enforce the capture and return of “fugitive slaves.” This compromise between the Southern slaveholders and the Northern free states defused a four-year political crisis over the status of territories colonized during the Mexican-American war (1846-1848). For the immediatist wing of the Abolitionist movement in Philadelphia, the implications of the new Fugitive Slave Law were clear: it had to be disobeyed and disrupted, even if that meant engaging in illegal activities to assist fugitives.[3]

By the early 1830s, the Abolitionist movement in Pennsylvania was starting to radicalize, reflecting developments on the national scene, such as David Walker’s 1829 Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World, and the 1831 Nat Turner slave insurrection. The older, mostly white Quakers, who had led the movement for decades, favored legal, non-violent measures for gradually abolishing slavery, while a growing tendency of mostly black abolitionists demanded the immediate abolition of slavery.[4] This growing dichotomy, between the gradualists and the immediatists, reflected the essential difference between reformist and revolutionary politics in the Abolitionist movement.

As the abolitionist movement became more immediatist in the 1830s, the Vigilance Committee, as it came to be known, emerged as the principal organizational form for assisting fugitives as well as victims of kidnapping. After black Abolitionist David Ruggles founded the first Vigilance Committee in New York City in 1835, Robert Purvis and James Forten formed the “Vigilant Association of Philadelphia” in 1837. Abolitionists in the rural counties surrounding these cities soon followed suit, becoming part of a regional network between Philadelphia, New York City, and other nearby cities, like Boston. The Vigilance Committees raised money, and provided transportation, food, housing, clothing, medical care, legal counsel, and tactical support for people escaping from slavery.[5]

The committee in Philadelphia was a racially integrated group that also included a (predominantly black) women’s auxiliary unit, the “Female Vigilant Association.” This degree of inter-racial and inter-gender organization was unheard of at the time, even in the Abolitionist movement.[6] The committee also included ex-slaves. Amy Hester Reckless, for example, was a fugitive who went on to become a leading member of the committee in the 1840s.[7]

While providing strategic resources to fugitives, the committee also carried out bold interventions. Members of the committee orchestrated two of the most notorious slave escapes of the 1840s: 1) that of William and Ellen Craft from Georgia, who used improbable disguises to make their way to Philadelphia in 1848, and 2) that of Henry “Box” Brown from Virginia, who arranged to have himself mailed in a wooden crate to Philadelphia in 1849. These daring escapes were widely publicized in the antislavery movement, and these fugitives appeared in public lectures in order to rally support to the Abolitionist cause. [8]

However, by the early 1850s, several waves of repression had left the committee disorganized. These included a string of crippling lawsuits against those who defied the Fugitive Slave Law, including participants in the Christiana Riot of 1851, wherein a slave-owner was shot and killed after attempting to capture a “fugitive.” A new organization was needed, so in 1852 William Still and other abolitionists established a new Vigilance Committee to fill the void left by the older, scattered one.[9]

Led by William Still, who had escaped from slavery as a child with his mother, the new Vigilance Committee was even more effective than its predecessor, assisting hundreds of fugitives every year in their quests for freedom. By the mid-1850s, Abolitionists had transformed Philadelphia into a crucial nerve center of the Underground Railroad, by then a massive network that spanned the U.S. and extended into Canada. The most prominent “conductors” of the Underground Railroad, people like Harriet Tubman and Thomas Garrett, directed hundreds of fugitives to the Vigilance Committee every year.[10]

Although the original Vigilance Committee was a clandestine organization, its reincarnation operated both publicly and in secret. Some of the members of the committee were lawyers who defended fugitives in the Pennsylvania courts, while others assisted fugitives using methods that were unequivocally prohibited by those same courts. Some even published their names and addresses in the Pennsylvania Freeman newspaper and in flyers so that fugitives could easily find them. In order to generate public support for their cause, they used the antislavery press and public lecture circuit to broadcast the success of their illegal activities—without revealing specific incriminating details and only after the fugitives were safe. Carefully documenting the daily operations of the committee, William Still wrote extensively about the hidden stories of slave resistance and the inner workings of their secret network. When he finally published The Underground Railroad Records in 1872, it would be the first historical account of the Underground Railroad. [11]

This delicate balance between secret operations and public activity was dramatically demonstrated in the summer of 1855, when William Still and others organized the escape of Jane Johnson and her children from their owner, John Wheeler, as they were en route to New York, docked in Philadelphia. During the escape, Passmore Williamson, one of the only white members of the Vigilance Committee, physically held back Wheeler, a well-known southern Congressman, while Still led Johnson and her children away to a nearby safe house. [12]

In the legal proceedings that ensued, a federal judge charged Williamson with riot, forcible abduction, and assault. The judge in the case rejected an affidavit from Johnson affirming that she had left on her own free will and that there had been no abduction, and Williamson spent 100 days in Moyamensing prison. The case became a national news story, as Abolitionists used the media to trumpet the success of the Johnson rescue, and to expose the southern slaveholders’ domination of the federal court system, which the Abolitionists called a “Slave Power Conspiracy.” Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, and other abolitionist leaders visited Williamson during his confinement, and wrote admirably of his actions in the antislavery press.[13]

The Philadelphia immediatists were fully aware of their strategic role in the national struggle against slavery. At a mass meeting in Philadelphia in August 1860, leader of the immediatist wing, William Still, explained that because they were “in such close proximity to slavery” and their “movements and actions” were “daily watched” by pro-slavery forces, they could do, “by wise and determined effort, what the freed colored people of no other State could possibly do to weaken slavery.”[14] By openly defying the Fugitive Slave Law in a border city, the immediatists in Philadelphia exacerbated the growing conflict between the free states of the North and the slave states of the South to a degree that few other Abolitionists could.

Through ups and downs, for nearly three decades, the Vigilance Committee acted as the organizational nucleus of the Underground Railroad in Philadelphia, a city that was publicly very hostile to Abolitionism. Most white workers opposed Abolitionism on racist ideological grounds, while the merchant elites and early industrialists of the city had close economic ties to slaveholders in the South and throughout the Atlantic. There where numerous anti-black and anti-abolitionists riots throughout the 1830s and 1840s in Philadelphia.[15] Even though they were persecuted for their cause, by subverting the Fugitive Slave Law in this border city, the immediatists—a radical minority within a minority—antagonized the slaveholders and their allies—a much larger and well-established enemy.

As the overall antislavery movement continued to grow throughout the North, the southern slaveholders went on the defensive. With the John Brown insurrection in Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1859, and the 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln, who campaigned against the expansion of slavery, the slaveholders in the South became more entrenched and alienated from the rest of the United States. In February 1861 the Lower South region of the U.S seceded, creating a separate country called the Confederate States of America, also known as the Confederacy. The U.S. national government, known as the Union, refused to recognize the Confederacy as a legal government. The Civil War officially began in April 1861, when Confederate soldiers attacked Fort Sumter, a Union fort in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. As the war took its course, Philadelphia Abolitionists, like Octavius Catto, shifted their strategy to radicalizing the Unionist cause from within. Catto and others organized the enlistment of black troops and advocating for a coordinated military assault on slavery in the South, for which they were strongly condemned by white Philadelphians.[16]

Before the war, and during its initial years, much of white Philadelphia was sympathetic to the Southern slaveholder’s grievances. But with the deepening of the conflict between North and South, most Philadelphians came to support the Union and the war against the Confederacy. A turning point came in 1863, when the city was threatened with Confederate occupation. Entrenchments were built and people fought to defend the city, defeating the Confederate Army at the Battle of Gettysburg.[17]

However, even with the shifting of opinion against the South, most white Philadelphians still believed that the Civil War had nothing to do with slavery. Many white Americans continued to believe that the Civil War was a “white man’s war” to preserve the Union and nothing more. Abolitionists and black Philadelphians continued to be the targets of mob violence, and some white Philadelphians even blamed the Abolitionists for the war.[18]

Having proclaimed the need to end slavery from the very beginning, Abolitionists identified the structural contradictions that tore the nation apart. But rather than wait for the gradual disintegration of slavery, the immediatists worked to hasten its destruction. In a society that was for the most part hostile to their cause, the immediatist wing of the abolitionist movement performed the historic duty of following through, with long-term consistency, those revolutionary tactics that alone could save the Union and drive the Civil War to a decisive conclusion. More and more slaves escaping from plantations, the enlistment of black troops into the Union army, the immediate emancipation of slaves throughout the South—these tactics were indeed the only ways out of the difficulties into which the Civil War had descended.

The Civil War had stemmed from a breakdown of a structural compromise that developed between two distinct modes of production—one based on northern industrial wage labor, and the other southern slave labor. The development of the antislavery movement over time made this “unholy alliance” impossible to maintain in the long run. In this, the Civil War confirmed the basic lesson of every revolution: either the revolutionary movement acts to accelerate strategic contradictions over time, breaking down all barriers to the attainment of its objectives, or it soon stagnates and is suppressed by repression and counter-revolution. This lesson stands the logic of gradualism on its head: revolution doesn’t advance with small increments, with legislative preconditions, but with prompt, uncompromising actions that destabilize the structural limits of the existing system.

The will for revolution can only be satisfied in this way—with strategic, revolutionary action. Yet the masses of people can only acquire and strengthen the will for revolution in the course of the day-to-day struggle against the existing class order—in other words, within the limits of the existing system. Thus, we run into a contradiction. On the one hand, we have the masses of people in their everyday struggles within a social system; on the other, we have the goal of immediate social revolution, located outside of the existing system. Such are the paradoxical terms of the historical dialectic through which any revolutionary movement makes its way. The immediatists overcame this contradiction by adapting themselves to the mass self-activity of the slaves, who in their day-to-day resistance to the slave system offered the abolitionists a means to realize their revolutionary objectives.

For over three decades, through ebbs and flows, victories and defeats, the immediatists consistently engaged with the everyday struggles of the slave class. They constructed multi-racial, multi-gender organizations that operated both legally and illegally, in order to help people emancipate themselves from slavery, to help them stay free, and to help them gain basic democratic rights. In doing so, they fostered the development of a revolutionary movement that precipitated the U.S. Civil War and culminated in one of the greatest social revolutions of world history—the emancipation and enfranchisement of million of slaves and workers in the South during the Reconstruction Era.

By the end of the Civil War, a once persecuted minority of fanatical Abolitionists were now national leaders. Today we see them as good-hearted activists, or even as moderates. But there should be no mistake about it—all Abolitionists were considered extremists. Few people believed that the slave system would fall. The Abolitionists certainly did not believe their revolutionary goal would one day become official government policy. In the end, the Abolitionists recognized the social and historical crisis in front of them, and the immediatists adapted to it better than any other Abolitionist tendency of their time.

“Lines,” Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

Though her cheek was pale and anxious,

Yet, with look and brow sublime,

By the pale and trembling Future

Stood the Crisis of our time.

And from many a throbbing bosom

Came the words in fear and gloom,

Tell us, Oh! thou coming Crisis,

What shall be our country’s doom?

Shall the wings of dark destruction

Brood and hover o’er our land,

Till we trace the steps of ruin

By their blight, from strand to strand?