Someone stands on a table and yells, “This is now occupied.” And that’s how it begins.

– Q. Libet, Pre-Occupied: The Logic of Occupation.

Introduction

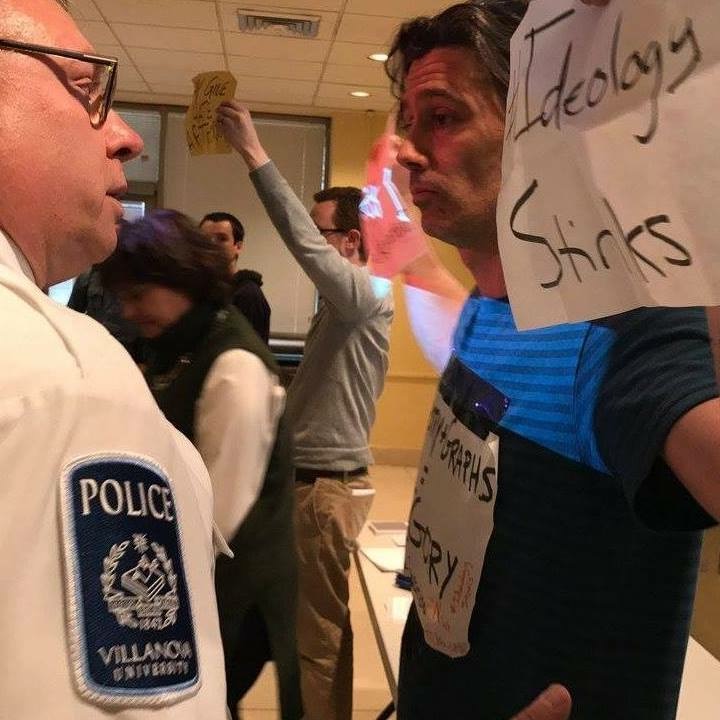

We know by now that fascists are targeting universities as recruiting sites and as places to make ideologies of racial, gender, and economic domination respectable (see this and this). Both liberals and conservatives are rushing to ensure that universities give fascists protected, well-funded platforms. What is the task of Antifa on college campuses? How can we be effective in combating the “fascist creep”?

Antifa’s powerful disruptions of fascist speakers help point the way. But that essential tactic has limits. It is often defensive, which leaves the university waiting for its next fascist cooption. What if the university could be more than a site to be defended? Can the struggle for campuses be not just reactive but transformative – wrenching universities out of the hands of fascists and liberals to make them sites of revolutionary power? We’ve seen glimpses of this possibility in the insurrections at the New School in 2008, at NYU in 2009, and throughout the wave of campus occupations in California in 2009 and 2010 -themselves reminders of the earthquake of student and worker struggle in May 68.

As a member of the Radical Education Department, part of the on-campus Antifa struggle, I offer the following: a strategy proposal for the experimental, insurrectionary seizing of campuses away from fascists and liberals. This insurrectionary approach could not only help create campuses entirely hostile to resurgent fascism; they could also help put powerful tools in the hands of radical left movements as they coordinate, expand, and develop, especially during key moments of social upheaval.

To make this proposal, I first frame it in the context of current American antiauthoritarian organizing. Then I analyze the crises shaking the university system, which reveal powerful possibilities and resources for radical action in and against that system. Finally, I chart some potential tactics by which to seize the means of intellectual production.

1. The University Struggle in Context

The horizontal, directly democratic struggles that surged after 2007 achieved important gains like reviving large-scale radical politics and producing a new generation of militant, antiauthoritarian organizers. The collapse of Occupy in the US, 15-M in Spain, and beyond in 2011 and 2012, however, reveals an important limit within the radical left today.

The kind of prefigurative organizing that stood at the heart of Occupy and related uprisings has been a crucial way of coping with the collapse of the revolutionary social movements of the 1960s and 1970s. In the absence of those larger, more powerful, and more coordinated struggles, prefigurative politics played an experimental role. Occupy’s emphasis on consensus, for example, made it possible to tentatively construct mass movements by not forcing any group to commit itself to a particular program, thus bringing together a wide range of groups and interests.

Despite its important role, larger prefigurative struggles are often unstable. Within Occupy’s coalitions, revolution-minded anarchists were constantly hounded by pious liberals wringing their hands in terror over the possibility of a broken window. After the state swept Occupy clear of the squares they were squatting, it was no surprise that the coalitions often scattered.

Movements like Occupy, then, highlight a central question for the antiauthoritarian left. How are we to create revolutionary, mass, and durable movements capable of eventually overthrowing capitalism and social domination?

In this context, the question of the university becomes: how can campus struggles add to the construction of those kinds of movements? In particular, how can we help lay the infrastructure for mass, federated action during the next wave of revolutionary struggle?

2. Crisis and Possibility in the University

The university is undergoing a series of fundamental crises within which we can spot possibilities for revolutionary struggle. What follows is only a brief sketch of those crises and possibilities.

A. Crisis of “Expert Knowledge”

Because it is the place where society’s experts and managers are trained, the university plays an important role in determining what counts as “real” knowledge – which is why the media often turn to professors to comment on current events. Strangely, the university is rejecting this role. Professors and administrators are not only refusing to judge the fascist ideology of racial and gender inferiority as right or wrong; they are also asserting that fascists have a right to free university endorsement, massive funds for protection and promotion, and highly publicized platforms to spread their ideologies.

But Antifa’s challenge to fascists on campus reveals an important opportunity. The struggle over university platforms suggests that they could increasingly become the conscious target of seizure and control by radicals. Those platforms are ready-made bullhorns by which to cultivate revolutionary theory and culture able to reach far greater numbers than many other outlets. One can imagine, for example, anarchists increasingly and actively (rather than reactively) seizing podiums at high-profile university events – hijacking and subverting media coverage with minimal effort.

B. Crisis of the Disillusioned Student

Traditionally, the university has been seen as a basic tool for social mobility – and so a justification for capital’s brutal inequalities. But the possibility of social climbing now looks increasingly ridiculous in light of ballooning of student debt and an economy geared towards “flexible,” part-time labor.

We have already seen some of the effects of this disillusionment: the underemployed recent graduate is often the engine driving movements like the Global Justice Movement, 15-M, and Occupy. The question was already asked by Research and Destroy in 2009: what is the point of college, other than disciplining us to manage a failing society?

The university, then, contains a highly disillusioned group – precisely what lures fascists on campus – and yet one that clearly can be radicalized for antiauthoritarian struggle. In this university crisis, the left could accelerate disillusionment and radicalization.

C. Crisis of the Disillusioned Worker

The vast majority of classes are now taught by contingent faculty – teachers without job security who often also lack benefits and receive poverty wages. Drives to unionize contingent faculty have begun, but a more radical possibility can be found here.

The precarious teacher is facing plummeting job prospects; the hope for tenure is now almost completely gone for most. But their precarity organically connects these teachers to the other disillusioned workers at the heart of so many recent uprisings, positioning it to bridge on-campus and off-campus struggles.

The college campus, then, is home to extremely volatile ingredients – disillusioned teachers students, alongside also exploited cooks, servers, and janitors. And those ingredients are combined in a place that also offers the potential for a platform through which to spread radical political organizations and ideas. If these could be properly combined, they could make the campus a thoroughly radical, even explosive, center.

3. Further Possibilities

But a college campus also has particular kinds of resources that, even beyond its volatile elements, make it an important target for radical seizure.

Communication

If a central job for radicals is assembling mass, revolutionary struggles, then one key element will be access to technological hubs for coordination and federation. We saw the importance of these kinds of hubs in N30. The radical overtaking of Seattle in 1999 was coordinated via Independent Media Centers – websites that communicated tactics and ideas. But in Seattle, activists managed those sites through physical IMCs – rooms full of computers and other resources (food, water, shelter) that made coordination and communication much easier and faster and that strengthened the sense of community and solidarity. We saw the importance of these centers in Seattle from the fact that police targeted them to choke off the uprising.

College campuses offer massive, free access to computers and the internet that could be communication hubs for radical struggles on and off campus. One valid ID and password could given an entire movement that access. More than this, some grad students and faculty are given unlimited free printing privileges – and again, only one person with that privilege could print an entire movement’s flyers, posters, zines, and papers for distribution.

But colleges also have libraries – and within them, mountains of information on past movements’ tactics, strategies, and ideas. College libraries are waiting to become part of a radical research center for ideas and histories that could feed directly into movements.

Spatial infrastructure

At the same time, radicals need centralized, reliable spaces for meeting, relaxing, sharing ideas, planning actions, and so on. This often means renting or squatting spaces across an entire city-scape, and those spaces are often available only on a temporary or unpredictable basis.

A college campus has a glut of unoccupied spaces ready to be used: halls, dorm lounges, library rooms or floors, theaters, and so on. On urban campuses, those spaces are not only relatively concentrated within one (often fairly central) part of a city, but also can be available more predictably.

4. Seize the Means: A Tactical Sketch

So what does it mean to seize the university through insurrection – to take hold of these possibilities and resources?

First, seizing the university means building radical, antiauthoritarian campus “cultures.” On the one hand, this entails what RED calls “guerilla education” – radical forms of education outside, beyond, and against the classroom that spread militancy and push a campus’s “common sense” far left. On the other hand, this means creating, multiplying, and federating radical groups on campus that are intolerant to fascism and willing to act in solidarity with radical struggles on and off campus. The Filler Collective, the Radical Education Department, anti-racist organizing, the Campus Antifascist Network, and radical struggles in solidarity with Palestine are examples of this work. The aim is to become a kind of disease, infecting other groups with leftist ideas while recruiting their most radical members. This is to “solidify” the radical left, as a pamphlet from the 2008 New School occupation puts it, creating zones of radical antiauthoritarianism on campus that spread and connect.

But it is not enough to aim for a radical leftist culture. Those cultures can become simply alternative spaces that leave the college basically untouched. What’s needed, I suggest, is an emphasis on direct, radical action. The Filler Collective, discussing a Pitt occupation, writes:

I sure as hell wasn’t radicalized after hitting up some student group’s meeting. I’m here because I’m still chasing the high from that first punk show in a squat house basement, that first queer potluck, that first renegade warehouse party, that first unpermitted protest, that first smashed Starbucks window. […]

Last November, a student-led march ended with a brief occupation of the Litchfield Towers dormitory lobby […] That night ended with radical questions circulating beyond our countercultural bubble for the first time in recent memory: Do the Pitt Police really have the right to beat the students they’re supposed to protect? Wait, don’t we pay to use that building? Well shit, do the police even have the right to dictate how students use our campus in the first place?

Insurrectionary actions reveal undreamt-of revolutionary possibilities. Without them, potential radicals remain stuck in a world with no alternatives.

In this way, overt tactics should be rooted in central, covert, insurrectionary tactics that take Antifa as a model. What I have in mind here, however, is not defensive but offensive, essentially devoid of protest: experimental seizures of resources and of symbolic spaces that show that the university can–and must–be in the autonomous control of radical leftist movements.

Occupations are a key example. In 2008 New School students overtook the cafeteria and study center; in 2013, students seized the president’s office at Cooper Union; at the National Autonomous University in Mexico, a building has been occupied by radicals for 17 years; and in the recent past, “in hundreds of universities across central and eastern Europe–students gather in the auditoriums of occupied buildings, holding general assemblies, discussing modalities of self-determination.” Such occupations are often reactions–to tuition hikes, e.g. – but they could become powerful offensive weapons.

Occupations should not be the limit of our imagination. Reclaim the Streets was genius in its guerilla actions, temporarily but radically overtaking and transforming roads, highways, and intersections. The same tactic could apply in a president’s office or at a campus event–perhaps making them unpredictable places to issue revolutionary communiques.

By creating offensive, radical campuses, we could create schools where no one would dream of inviting a fascist ideologue. More than this, campus insurrections are practice for the next revolutionary moments, when we’ll be ready to take hold of the university’s and society’s resources in order to put them at the service of broader struggles. In the words of Research and Destroy, “We seek to push the university struggle to its limits. […] [W]e seek to channel the anger of the dispossessed students and workers into a declaration of war.”

The insurrectionary campus: not just defending against fascism, but making the university a tool of social revolution.

This is particularly important because both of these camps are defenders of imperial capitalism, and the major difference is in their public relations campaigns. If liberals want to keep the gloves on and conservatives take them off, they both agree that the world should continue to be unremittingly pummeled by top-down global class warfare.

This is particularly important because both of these camps are defenders of imperial capitalism, and the major difference is in their public relations campaigns. If liberals want to keep the gloves on and conservatives take them off, they both agree that the world should continue to be unremittingly pummeled by top-down global class warfare.