from Gathering Forces

“…the more alien wealth they [the workers] produce, and… the more the productivity of their labor increases, the more does their very function as means for the valorization of capital become precarious.”[1]

“…within the capitalist system all methods for raising the social productivity of labor are put into effect at the cost of the individual worker; …all means for the development of production undergo a dialectical inversion so that they become means of domination and exploitation of the producers…”[2]

The Theory of Immiseration

How are we to understand the contemporary economic situation of most people, who experience increasingly unstable conditions of employment and life?

This essay analyses the growth of poverty and income inequality within the context of a developed capitalist[3] economy, using Philadelphia as a case study. Some might think that this city is an extreme example; for many years now Philadelphia has ranked the poorest of the 10 largest metropolitan areas in the United States.[4] However, the basic thesis of this essay is that immiseration is not an exception but instead a normal outgrowth of the capitalist economy.

The concept of immiseration is usually associated with Karl Marx, who insisted that the nature of capitalist production resulted in the devaluation of labor, specifically the decline of wages relative to the total value created in the economy. For Marx, this meant that the proletariat class,[5] or working class, was fundamentally defined by precariousness, i.e. material instability, uncertainty, insecurity, and dependency. This theory stems from Marx’s analysis of the changing organic composition of capitalist production and the reduced demand for labor that emerges as technology develops and labor becomes more productive. With increasingly productive machines, less labor produces more commodities at a faster rate, leading to the gradual replacement of labor by machines. Marx observed that the realities of capitalist competition necessitated this tendency towards mechanization and rising productivity. If a factory in the South restructures production to raise its productivity—allowing it to sell more commodities, at a faster rate, and at a cheaper price, while employing less labor—while a rival factory in Philadelphia does not, then after a while the factory in the South will run the factory in Philadelphia out of business. In order to protect their market from more productive competitors, therefore, capitalists must reinvest part of their capital into increasing productivity, or perish in the long run.

As capitalists competed and became more productive, Marx noted that labor became more impoverished: “The growing competition among the bourgeois, and the resulting commercial crises, make the wages of the workers ever more fluctuating. The unceasing improvement of machinery, ever more rapidly developing, makes their livelihood more and more precarious.”[6] In other words, increases in capitalist productivity were uneven in their effects—they benefited the capitalists, not the workers. As capitalism became more productive and labor produced more capital in a given amount of time, economic output increased; but at the same time, real wages stabilized and even declined, because the input of human labor stayed the same or declined relative to the output of capital.

This constellation of ideas would later be referred to by Marxists as “the immiseration thesis.” However, this term is somewhat misleading since throughout his life Marx developed several theses about the absolute and relative immiseration of labor under different phases of capitalist development. Nonetheless, Marx always theorized the devaluation of labor relative to the self-valorization of capital, and in this sense, he did posit a general theory of immiseration.

An Uneven Economy

Even accounting for periodic crises and recessions, it seems that the US economy is strong and growing, locally and nationally, from the standpoint of those who rule it— the capitalist class.[7] It is still the largest national economy in the world;[8] the world’s largest producer of petroleum and gas[9]; the world’s largest internal market for goods and services[10]; and the world’s largest trading power,[11] with roughly a third of this trade based in the export and import of international commodities, while domestic trade between regions in the US generates even more capital, accounting for roughly two-thirds of US trade.[12]

The majority of this trade is concentrated in the 10 largest metropolitan areas of the US. Those ten metro areas, ordered by largest total trade volume, are: New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, Dallas, Philadelphia, Atlanta, Detroit, San Francisco, and Boston. All the commodities that move throughout the nation, in freight trains, trucks, and shipping containers, flow through a vast transportation infrastructure made up of rail lines, roads, and ports that link these ten metropolitan areas in an extensive network of “trade corridors.” New York and Philadelphia, Los Angeles and Riverside, and San Francisco and San Jose are among the largest corridors within the national network.[13] These regional trading networks also provide access to distant markets that allows US capitalists to take part in global commodity chains. Still, the largest single part of capitalist value in the US comes from domestic trade.

Primarily as a result on their complementary industries in energy, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and mixed freight, New York and Philadelphia are the largest trading partners in the national interstate network,[14] making the New York-Philadelphia trade corridor the most valuable in the nation.[15] Because it serves as a crucial node in the national trade network, Philadelphia is home to the 7th largest metropolitan economy in the nation,[16] generating the 4th highest gross domestic product in the nation, and the 9th highest among the cities of the world.[17]

The Philadelphia metropolitan economy, which includes Camden, Chester, Norristown, and other peripheral cities and towns, continues to generate massive profits for those who own it. Still, for most people—who are not capitalists, but workers—wages are low, jobs are increasingly insecure, and poverty continues to grow.[18] Despite regional economic growth, poverty has increased more rapidly in Philadelphia than any other major city since the 1970s. However, this trend is not isolated to Philadelphia; poverty has steadily increased throughout the nation since the 1970s.[19]

In the same time period that people became poorer, the national economy continued to grow and wealth continued to concentrate in fewer hands than ever before. After two decades of relative stability following World War Two, US income inequality once again began to grow starting in the early 1970s and continued to grow despite rising business cycles in the 1980s and 1990s.[20] By 2013, the top 1 percent of households received about 20 percent of all pre-tax income, in contrast to about 10 percent from 1950 to 1980.[21] By 2017, the income of the top 20% of households in Philadelphia was up by 13% since 2007, while the income of the bottom 60% of households was below 2007 levels.[22]

While a strong national economy in the late 1990s helped drive down the number of people living in poverty for the first time in decades, this trend was short-lived. Not long after the 2000s began, the bursting of the dot-com bubble sent the nation into a recession, a regular occurrence in capitalism. Millions of people lost their jobs and incomes during the early 2000s, and poverty continued to grow even as the economy recovered by the mid 2000s. The onset of the Great Recession of 2008-2009 only accelerated this trend, and the number of people living in poverty grew even faster. Even with the end of the Great Recession, poverty continued to grow throughout the nation, and Philadelphia registered declines in typical worker wages during the first five years of the recovery. By 2010-2014, 14 million people in Philadelphia lived in neighborhoods with poverty rates of 40 percent or more—5 million more than before the Great Recession and more than twice as many as in 2000.[23]

Although poverty increased among white Americans in the post-Recession period, for black Americans and Latino Americans poverty rose even more sharply, locally and nationally.[24] In particular, black Philadelphians today continue to experience record high levels of poverty[25] and low teen employment.[26] This racial disparity is the result of a longstanding pattern in which white workers, allied with capitalists (who are almost entirely white), exclude black and brown workers from the better paying, more secure jobs.

The De-Industrialization of Labor

How do we explain this disconnect, between growing wealth at the top, and deepening poverty at the bottom?

It’s obvious in retrospect that the rise of poverty in Philadelphia and other former industrial centers is the result of a shift in the capitalist mode of production—from manufacturing industries to service industries, and from city to suburbs. During most the 19th century Philadelphia was a center of craft-based industrial production, well-known for its diverse array of small and medium-sized manufacturing industries—textiles, metal products, paper, glass, furniture, shoes, hardware, etc. By 1900, manufacturing workers made up about one-half of the city’s entire labor force.[27] However, manufacturing jobs began to decline in Philadelphia in the 1920s, and by the 1970s, the service industries came to eclipse manufacturing entirely. Rather than manufacturing, most people now work in the service industries—food service, retail, health service, and logistics sub-industries such as warehousing, transportation, and delivery services. This “de-industrialization” of the economy and workforce resulted in a loss of income for most workers.[28]

The de-industrialization of Philadelphia, and the corresponding rise in poverty throughout the region, began earlier than most other cities in the North American Rust-Belt, shortly after the economic upturn that came with World War One (1914-1918), which resulted in growing mechanization, automation, and standardization of production on a national and global scale. In contrast, Philadelphia’s manufacturing businesses for the most part continued employing the labor of highly skilled craftsmen who worked in small and medium-sized firms, known as “workshops,” which produced custom goods for niche markets. The “Workshop of the World,” as Philadelphia was still known in the 1920s, could not compete with mass industrial production, for mass marketed consumption, by means of the unskilled and disposable mass assembly line workers of the factories in Northern cities like Detroit, Chicago, and New York. The new system of mass industrial production signaled the end of the highly specialized manufacturing processes which characterized most of industrial Philadelphia before World War Two.[29]

With the national economic downturn of 1929, major sections of the city’s craft-manufacturing base began to collapse. By the 1930s, the only manufacturing businesses that remained in Philadelphia were the few that developed mass production methods—factories along the peripheries of the city in Manayunk, Germantown, Kensington, etc. These were the only manufacturing businesses in the city that could actually compete on a national level.

Eventually, the demand for manufacturing in Philadelphia would pick up as a result of the revival of the national economy during World War Two (1939-1945), when federally funded factories hired over 27,000 new workers.[30] The wartime economy opened new possibilities for black workers to join the industrial workforce; while only 15,000 African-Americans worked in manufacturing jobs in the city in 1940, their representation rose to 55,000 by 1943. Although this represented an increase in wages and jobs for black workers, more than half of these jobs were in unskilled positions that offered the lowest wages.[31]

Despite a boost in production during World War Two, Philadelphia’s manufacturing industries began a steep decline during the peacetime transition. Industrial capitalists continued to face the challenge of superior competition, and this time the competition was increasingly global. International trade grew in the decades after the war, as European and Japanese manufacturers began to compete with US manufacturers. In this context, most factories in Philadelphia either went out of business or left the city. By 1955, fewer than 1,000 workers were employed in the city’s formerly expansive textile industries.[32]

Black industrial workers hired during World War Two were particularly affected by the loss of manufacturing jobs. A big factor in this process was the seniority system embodied in most union contracts, which meant that when recession, closure, or layoffs happened, those with the least seniority were the first to go. Since black workers were usually the last hired, they were also usually the first fired.

By the early 1970s, when other major cities throughout the North and Midwest were beginning to experience de-industrialization, most of the manufacturing businesses in Philadelphia had already shut down or relocated to the suburbs, as well as to cities in the South and West of the country. The few industrial firms that remained in Philadelphia were those that invested heavily in automation and raised their standard of productivity.[33]

In the 1980s and 1990s the pattern of de-industrialization became international, as it began to hit most nations in Europe, as well as Japan, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada. Since the beginning of the 21th century, the Southern and Western cities of the US that once drew manufacturers from the older cities have also struggled with the loss of manufacturing jobs. After the economic crisis of 2008, the effects of de-industrialization only intensified on a global scale, especially in underdeveloped nations in the global South.[34]

In conclusion, the de-industrialization of Philadelphia, and the concomitant rise in poverty, was mostly the result of capitalist market competition. Industrial Philadelphia was mostly composed of craft-based manufacturers; these could not compete with highly mechanized and increasingly automated factories elsewhere. The manufacturers that kept up their profits in the face of competitors stayed in business by investing in technology that increased productivity. Some also relocated their businesses to cheaper, less regulated labor markets. In the process, these transformations led to the devaluation and displacement of labor.

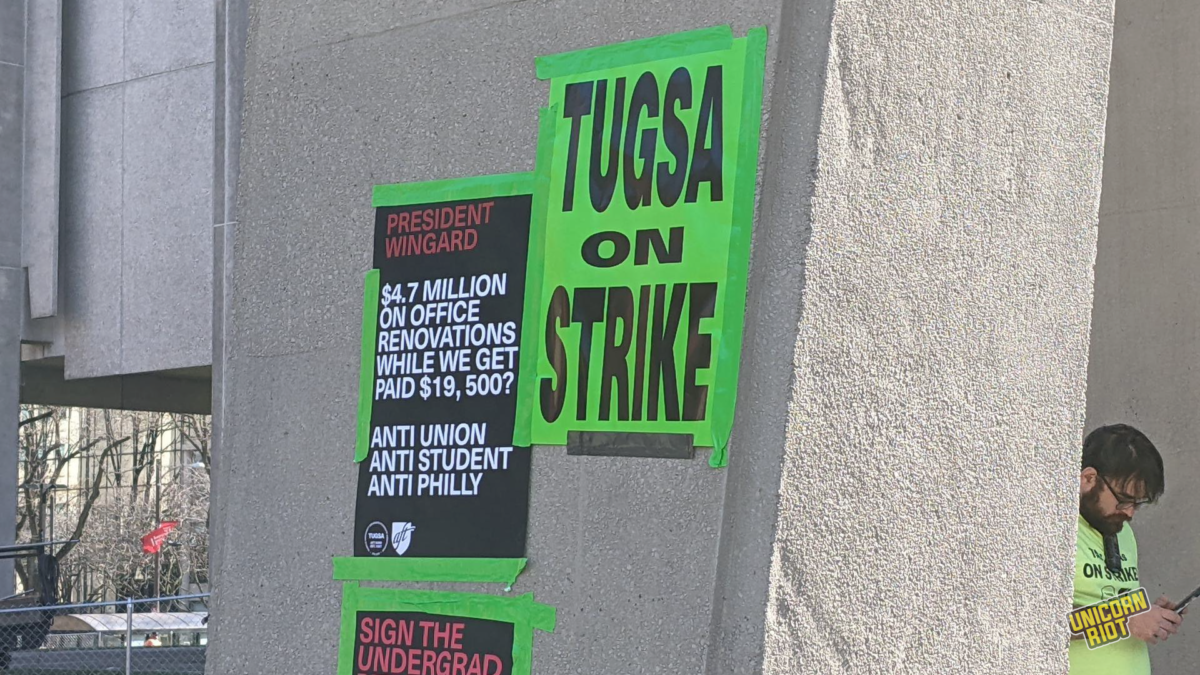

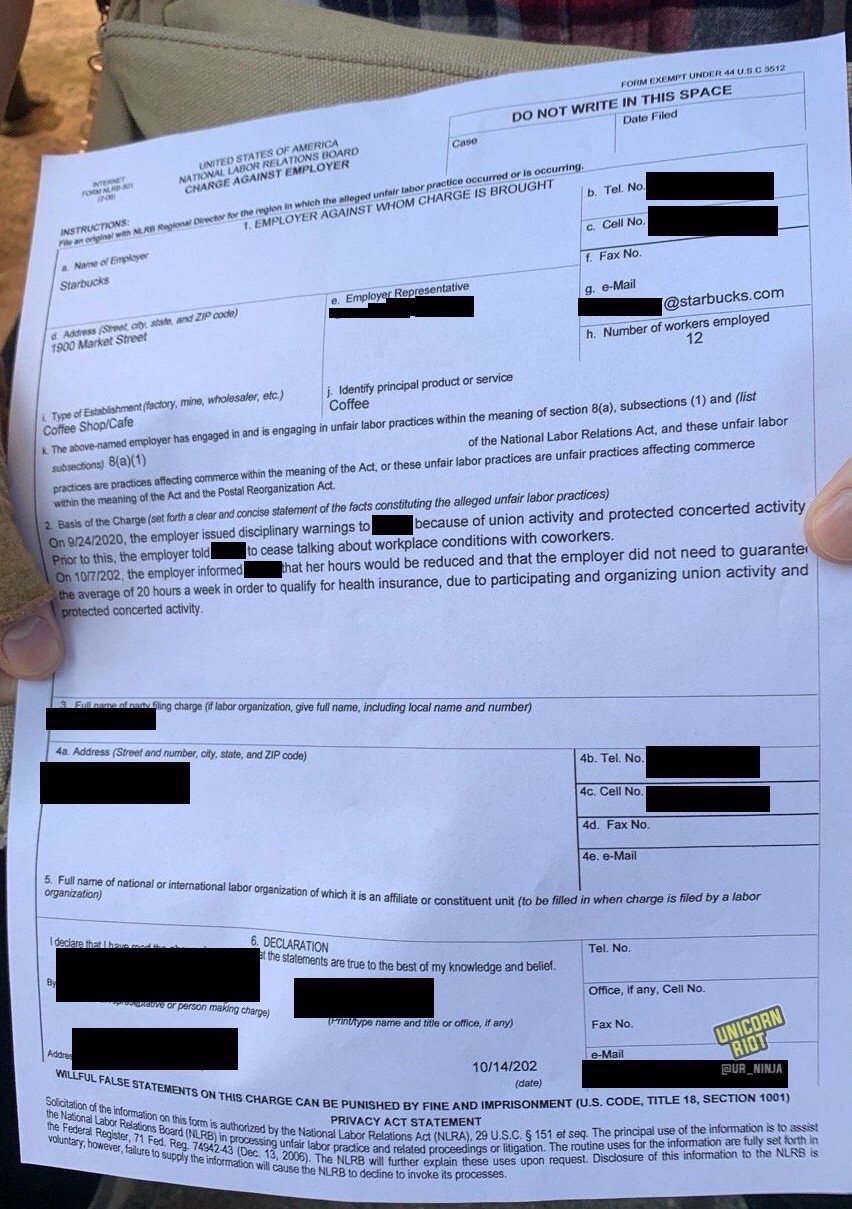

Besides the pressures of market competition, another important factor influencing de-industrialization was the militant resistance of the workers who carried out mass strikes and secured higher wages, pensions, health benefits, and better working conditions during the 1930s and 1940s. With the help of the leadership of the major industrial unions (the American Federation of Labor and the Congress of Industrial Organizations), the capitalist class responded to the workers movement by shutting down or relocating their facilities to the non-unionized South and West in the 1950s. In this way, de-industrialization undermined the power of the unionized working class, and took back the wages and benefits that the capitalists conceded to the workers in previous decades of struggle.

The Growth of Inequality

As capitalism reorganized itself, the service industries came to supersede manufacturing as the primary source of working class employment. Today, the number of industrial jobs in Philadelphia represents only 5 percent of the total workforce of the city, while service jobs represent 40 percent of total employment, making the service industries the largest sector of the city’s workforce.[35] Even within the few manufacturing businesses that remain in the region, they employ increasingly fewer workers, and those they do employ are increasingly part-time, part-year and paid less.[36]

The social composition of the service industries is much more diverse than that of the manufacturing industries, which are highly unionized and still dominated by white men. Women make up over half of all service workers, while black workers form a higher than average concentration in lower-paying service jobs. While service jobs have grown by 56 percent since the 1970s, the overwhelming majority of these jobs are part-time, part-year, require few skills, pay low wages, and offer few to no benefits. At the same time, the number of high salary professional and managerial jobs has grown by 85 percent since the 1970s.[37] This means that de-industrialization has improved the earnings of those in the top-tier of the workforce, while most workers have seen their incomes shrink or stagnate since the 1970s.

Further exacerbating the livelihood of the urban proletariat, jobs have increasingly shifted towards the suburban peripheries of the city, after the pattern of large cities throughout the Northeast and Midwest. This transformation was facilitated by the massive construction of interstate highways in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. While low-income populations in the region concentrate in Philadelphia, Camden, and a number of older urban centers, most jobs are now in the suburbs, often in areas accessible only by automobile, and distant from housing that is affordable to these workers. If city residents do manage to find a job in the suburbs, their wages are effectively lowered because of substantial traveling expenses; if they decide to move to the suburbs, wages are effectively lowered because of higher rent.[38]

The decline of manufacturing jobs was particularly devastating for black workers, who concentrated in unskilled manufacturing jobs and in service jobs within the city, but were almost completely excluded from professional/managerial jobs and skilled trades. As a result of the loss of manufacturing jobs, coupled with the suburbanization of the rapidly expanding service industries, black workers have seen their incomes and jobs decline dramatically since the early 1970s. Although employment rates declined for both white and black men since the 1970s, the black decline was twice that of whites. Furthermore, while there was an increase of employment for white women in Philadelphia since the 1970s, the employment rate for black women hardly changed at all.[39] In this way, de-industrialization eroded the gains made by black workers in the industrial sector in the decades after World War Two.

The Immiseration of Labor

As I’ve shown, the transformation of the Philadelphia economy—from manufacturing to services, and from city to suburbs—has resulted in a deepening of poverty and inequality for most workers in this city. The question remains, why does capitalism develop itself in such a way that results in the immiseration of labor? This much is clear from the outset: nature does not produce, on the one hand, fewer and fewer rich people, and on the other hand, a growing army of workers who own nothing but their labor, which they must sell for an increasingly lower wage. The immiseration of labor results from the contradictions of what Marx called the “capitalist mode of production.”

In brief, Marx argued that capitalism was distinct from all other modes of production in its unique aim: the creation of capital. Whereas other modes of production might find their purpose in producing useful things to satisfy human needs (communal production), or in producing a surplus of luxuries to satisfy a class of nobles (feudalism), capitalism, in contrast, produces the abstraction known as capital. Capital is not produced for the private consumption of its owner, the capitalist. If this were the case the aim of capitalist production wouldn’t be the creation of capital but the consumption of things (or what Marx called “use-values”). Under capitalism, however, capital is not produced for use or consumption; capital functions as an end in itself—it is the starting and finishing point of production.[40]

Beginning with the industrial revolution in the late eighteenth century, capitalists made labor more productive by investing a greater part of capital into the instruments of production, introducing newer, more efficient, and more expensive machines. Such an accelerated development of the forces of production did not exist in any other mode of production before capitalism. Theoretically, this heightened level of productivity could raise people’s standard of life while reducing the amount of time that they have to labor for others. However, Marx was quick to point out that “[capitalist] production is only production for capital and not the reverse, i.e. the means of production are not simply means for a steadily expanding pattern of life for the society of the producers.”[41] Under capitalism, labor is only an instrument for the valorization of capital, i.e. capital accumulation, and nothing else. Instead of serving the needs of society as a whole, capitalist production serves the specific needs of capital accumulation, which requires the devaluing of labor in order for capital to expand. The immiseration of labor, therefore, is not an aberration, but a fundamental feature of the capitalist mode of production.[42] Thus, Marx concluded: “On the basis of capitalism, a system in which the worker does not employ the means of production, but the means of production employ the worker, the law by which a constantly increasing quantity of means of production may be set in motion by a progressively diminishing expenditure of human power, thanks to the advance in the productivity of social labor, undergoes a complete inversion, and is expressed thus: the higher the productivity of labor, the greater is the pressure of the workers on the means of employment, the more precarious therefore becomes the condition for their existence, namely the sale of their own labor-power for the increase of alien wealth, or in other words the self-valorization of capital.”[43] This is a fundamental contradiction of capitalist development: as capitalism becomes more productive, and the means of production become more extensive and technically more efficient, the labor that works up those means of production becomes increasingly devalued and unnecessary.

According to Marx, the drive to accumulate capital at the expense of labor is not based on greed or any other negative psychological trait on the part of the capitalist. If a capitalist does not accumulate capital, if profits are not continually transformed into a further increment of value, then that capitalist is unable to keep up with competitors and eventually goes out of business.[44] This is what Marx refers to as the coercive law of capitalist competition. Workers lose their jobs and their incomes not because of the ill will of particular capitalists, but because the sole aim of capitalism is the valorization of capital, which depends on the maximum extraction of value from labor. In the face of obstacles like market competition and (to a lesser degree) labor struggles, capitalists perpetuate the accumulation of capital by reducing jobs/wages/hours, mechanizing and automating production, and relocating to cheaper, less regulated labor markets.

Marx provided us with the analytical tools for thinking about this internal contradiction of capitalist development—the contradiction between the declining value of labor and rising surplus value, i.e. the basis of capital formation. As capitalist production becomes more productive, the working class can only become more precarious, since the increasing accumulation of capital requires an increasing devaluation of labor. This contradiction is inherent to capitalism—it arises independently of the level of class struggle, fluctuations in wages, state interventions in the economy, or economic crises. At the same time, the relative intensity of the immiseration of labor can rise or drop with the limits set by the accumulation process, depending on the degree of control that workers as a class exert over the economy and the state. At different times in history workers have asserted their interests over and against the drive for capital accumulation, and as a result, have been able to gain a larger share of the total value that their labor produces. Still, for Marx, even if wages and standards of living rise for a time, this does not end the immiseration of labor. That would require the end of capitalism.

Implications for the Future

The story of the immiseration of labor in Philadelphia is particular but not exceptional; it can serve as the basis for general observations on the dynamics of labor-capital relations within a developed capitalist economy. Capitalists in Philadelphia adapted to the challenges of market competition and labor struggle in much the same way that capitalists did in most mid to large-sized manufacturing centers—by shutting down, relocating, and/or automating production. Over time, the bulk of jobs in most US cities shifted to the services sector and to the suburbs. In every city that these changes took place the results where the same: the decline of wages and regular employment for the urban poor.

After having analyzed the antagonistic nature of capitalist production, we can see that the immiseration of labor is the natural result of capitalist development. Therefore, there is no prospect for a return to a so-called “golden-age” of capitalism characterized by moderate wages, benefits, and full-time employment. The easing of income inequality in the developed nations immediately after World War Two was an exception, not the rule, in the history of capitalism. Outside of this brief period in the 1950s and 1960s, capitalism has not delivered on its promise of upward class mobility for most workers, and this promise can only continue to fade as capitalism continues to develop.

Today, most people find themselves within the throes of a drawn-out process of immiseration that shows no signs of reversing itself. Incomes have declined since the 1970s to allow for a greater acceleration of capital formation and accumulation. Even as total economic output continues to increase, and even as the job market continues to grow, working class incomes continue to decline, since most jobs are now in the unskilled, unprotected, low-wage service industries. Under these circumstances, the instability that a developed capitalist system subjects the employment and working conditions of the workers becomes a normal state of affairs.[45] The production process reaches a point of no return, continually reproducing a permanently marginalized mass of low-paid laborers with no hope of a professional career.

Rather than functioning as a site for upward mobility and income growth, the late capitalist megalopolis increasingly functions as a warehouse for low-wage service workers. Over the past fifty years, these structural trends have steadily asserted themselves on global level, especially in the global South.[46] As Mike Davis painstakingly details in his devastating book, Planet of Slums, poverty and occupational marginality are especially prevalent in the cities of underdeveloped nations, where urban existence is increasingly disconnected from mass employment. With unprecedented barriers to large-scale emigration to developed nations, slum populations continue to grow at an unprecedented rate in the global South. For Mike Davis, this is the real crisis of world capitalism: the crisis of the reproduction of labor and the inability of capitalism to stabilize (yet alone improve) the livelihood of the proletariat.

The growing division of the workforce into 1) a small, privileged core of professionals and managers that can expect continuous, high-paying employment, and 2) a large periphery of precarious “floaters,” to which capitalists provide little more than a low wage, for as long or as short a time as capitalists require these workers—this division will only widen as capitalism continues to develop. To the extent that most workers have access to increasingly irregular employment and smaller wages, the trend toward racial and class inequalities will persist, globally and locally. Black workers will continue to be the “last hired, first fired.” White workers will continue to act as labor aristocracy, allying themselves with capitalists to monopolize the professional and managerial jobs, while relegating workers of color—especially black workers—to the worst paying, least secure, lowest status jobs.

The housing market will continue to reflect the uneven distribution of income and jobs. The white workers who hold the managerial and professional jobs will continue to predominate in the suburbs, or in some comfortable, tree-lined areas of the city like Chestnut Hill, and in the gentrifying neighborhoods close to center city. In contrast, low-income workers will remain in the vast stretches of row houses in Philadelphia and Camden and in the older suburbs like Chester or Norristown.

The Struggle For a Classless Society

Capital seeks to gain their greatest return on its investment in labor and means of production. In pursuing this end, capital has reorganized the production process and with it the realities of working class existence. This raises strategic questions from the standpoint of class struggle: what forms of struggle are developing today that point to a different future? If industrial production created a particular conception of class struggle, what do the service industries mean for the future of class struggle? What does working class power look like in the context of a service economy?

These are complex questions that must be explored via further research of the class composition and dynamics of class struggle in specific regions. Unfortunately, this is beyond the scope of this essay, which at the most serves as the groundwork for such an investigation. Still, on a general level, this research makes this much clear: as long as capitalism continues as the dominant state of affairs, the contradiction between capital and labor can only become more pronounced. Therefore, it is not enough to reform capitalism or morally condemn capitalists—we must develop a plan to overthrow the structure of capitalism in its entirety.

Of course, the design and implementation of such a plan would take different forms depending on the conditions of working class existence in different regions. Nonetheless, at its core, this plan must entail the abolition of private property in the mode of production and the organization of a system of production that is no longer carried out with the goal of capital accumulation, but instead in a way that is systematically regulated by society—not the capitalists, not the market, not the state, but society as a whole. The members of such a society would have to reorganize the production process in such a way that frees their labor from the constraints of capital—an external, independent force standing above society.

However, given the contemporary circumstances of late capitalism, it is unclear whether workplace-centered struggle is the primary organizational form for building this social project. Even though capital continues to accumulate in industrial production, employment has shifted from the sphere of direct commodity production (agriculture, manufacturing) to the sphere of circulation (services). In such an economy, workplace struggles pose little to no threat to capitalism. Even if workers took over every McDonalds or Walmart, the economy would continue to operate in highly automated essential sectors like agriculture, construction, manufacturing, and logistics. If a proletarian revolution were to occur in such a context, the communization of production would not entail proletarian control of workplaces—as conceived by the traditional approach to labor struggle—so much as proletarian expropriation and elimination of workplaces, most of which are nonessential (i.e. most of the services industries) and serve no useful purpose outside of the context of capital accumulation.

The critical period in US mass industrial relations, which began about a century ago and saw a rapid growth in the power of industrial workers’ unions in the 1930s and 1940s, was followed by capitalist counter-organization and restructuring. By the early 1980s it was clear that the New Deal order of relatively strong labor unions was over in the US. Today, the material basis for workplace oriented struggles has fallen apart, shattered by capitalist automation, deindustrialization, and decentralization.

Despite these difficulties, there is still no logical argument for why a classless society is impossible. Even when such a society can only be achieved with difficulty and struggle—in light of rising poverty and racial inequality; in light of constant imperialist wars; in light of the ecological destruction brought about by capitalism—in light of all that, there are still good reasons to fight for a world beyond capitalism, where production is carried out by an association of free people who collectively regulate their own labor. To be victorious, however, we must build organizations that correspond to the present circumstances, instead of simply inheriting the idealized and ready-made organizational forms of the past.