from The Conversation

While New York City is commonly considered the birthplace of American punk rock, just 100 miles south of the famous CBGB club where the Ramones and other early punk bands got their start is Philadelphia, which has had its own vibrant punk rock scene since at least 1974 – and it has persisted through the present day.

I am a professor of sociology at Mercer County Community College in New Jersey, lead editor of a forthcoming edited volume titled “Being and Punk,” and author of the 2016 book “Ethics, Politics, and Anarcho-Punk Identifications: Punk and Anarchy in Philadelphia.”

I’ve been a fan of punk rock music since I was 15 years old and have been an active member of punk scenes in Philadelphia and Fargo, North Dakota. I still attend punk shows and participate in the scene whenever I can.

Though the “birth” of punk is always a contentious subject, it is fair to say that, with the Ramones forming in 1974 and releasing the “Blitzkrieg Bop” single in February 1976 in the U.S., and the Sex Pistols performing their first show in November 1975 in the U.K., punk is at least 50 years old.

Given this milestone, I believe it’s worth looking back at the heyday of the anarchist-inflected punk scene in Philly in the 1990s and 2000s, and how the political ideology and activism – encouraging opposition to capitalism, government, hierarchy and more – is still influential today.

‘Not your typical rebellion’

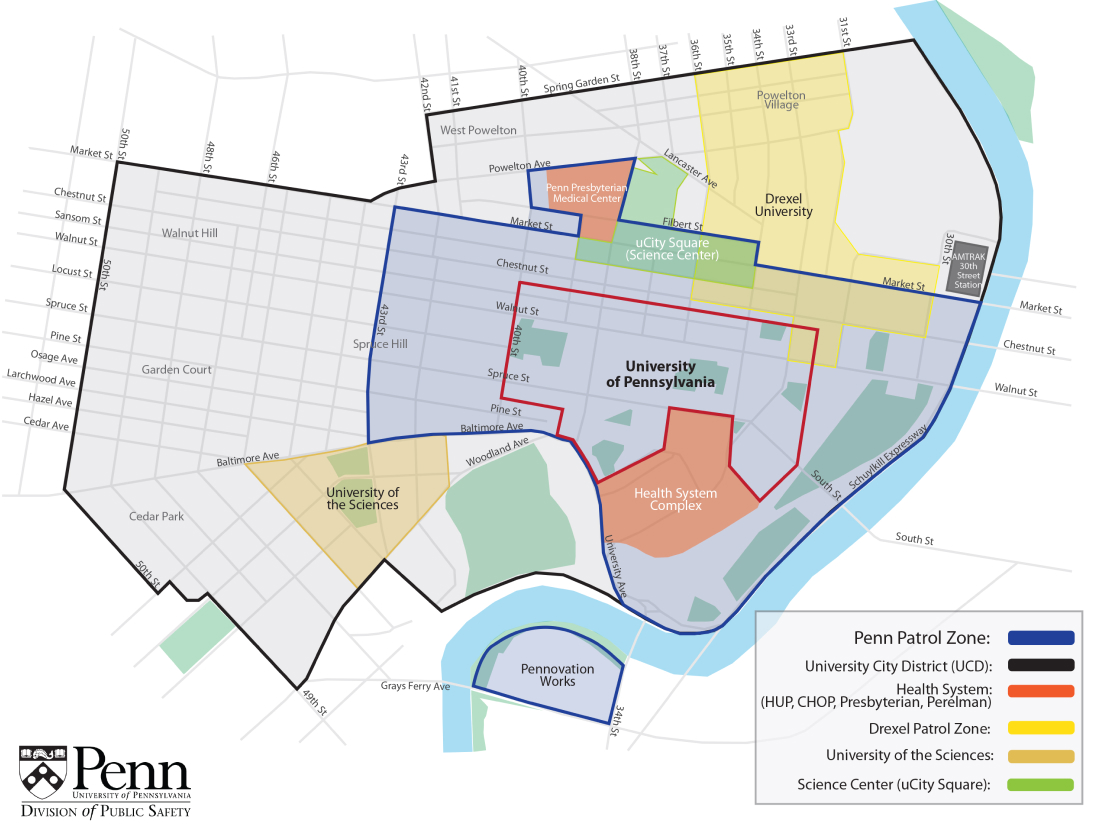

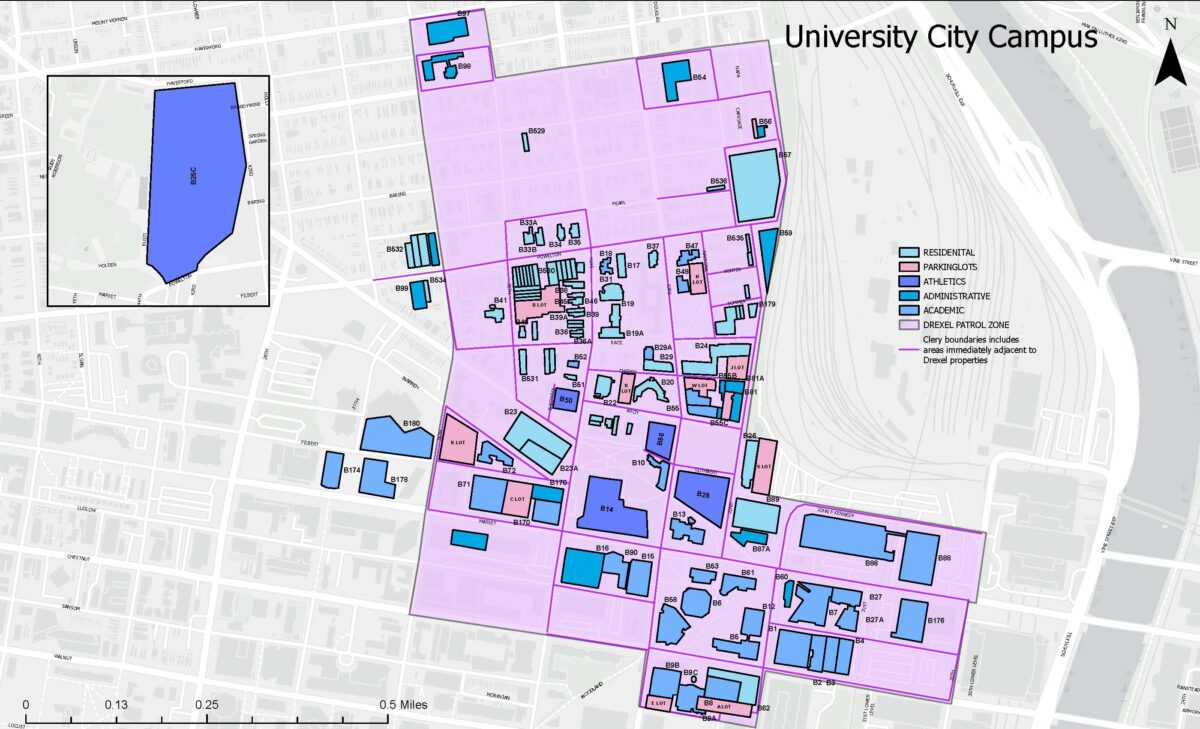

In Philadelphia, and especially in West Philly, a number of collectively organized squats, houses and venues hosted shows, political events and parties, along with serving as housing for punks, in the 1990s and 2000s. In some cases, the housing itself was a form of protest – squatting in abandoned buildings and living cooperatively was often seen as a political action.

There was the Cabbage Collective booking shows at the Calvary Church at 48th and Baltimore Avenue. Stalag 13 near 39th and Lancaster Avenue is where the famous Refused played one of their final shows, and The Killtime right next door is where Saves the Day played in 1999 before becoming famous. The First Unitarian Church, an actual church in Center City, still regularly puts on shows in its basement.

These largely underground venues became central to the Philadelphia punk scene, which had previously lacked midsized spaces for lesser known bands.

Many Philly punks during this era mixed music subculture with social activism. As one anarcho-punk – a subgenre of punk rock that emphasizes leftist, anarchist and socialist ideals – I interviewed for my book told me:

“My mom … said, ‘I thought you were going to grow out of it. I didn’t understand it, and your dad and I were like, ‘What are we doing? She’s going out to these shows! She’s drinking beer!’ But then we’d be like, ‘She’s waking up the next morning to help deliver groceries to old people and organize feminist film screenings!’ We don’t know what to do, we don’t know how to deal with this; it’s not your typical rebellion.’”

This quote captures the complex and ambiguous rebellion at the heart of anarcho-punk. On the one hand, it is a form of rebellion, often beginning in one’s teenage years, that contains the familiar trappings of youth subcultures: drug and alcohol consumption, loud music and unusual clothing, hairstyles, tattoos and piercings.

However, unlike other forms of teenage rebellion, anarcho-punks also seek to change the world through both personal and political activities. On the personal level, and as I showed in my book, many become vegan or vegetarian and seek to avoid corporate consumerism.

“I do pride myself on trying to not buy from sweatshops, trying to keep my support of corporations to a minimum, though I’ve loosened up over the years,” another interviewee, who was also vegan, said. “You’ll drive yourself crazy if you try to avoid it entirely, unless you … go live with [British punk band] Crass on an anarcho-commune.”

Love and rage in the war against war

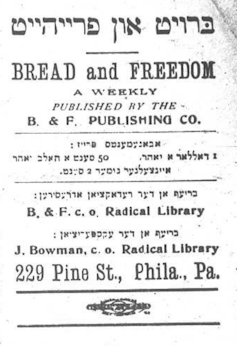

Philly’s punk activists of that era spread their anarchist ideals through word and deed.

Bands like R.A.M.B.O., Mischief Brew, Flag of Democracy, Dissucks, Kill the Man Who Questions, Limp Wrist, Paint it Black, Ink and Dagger, Kid Dynamite, Affirmative Action Jackson and The Great Clearing Off, The Sound of Failure, and countless others, sang about war, capitalism, racism and police violence.

For example, on its 2006 single “War-Coma,” Witch Hunt reflected on the ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, laying blame on voters, government and religion:

24 years old went away to war / High expectations of what the future holds / Wore the uniform with pride a rifle at hand / Bringing democracy to a far away land / Pregnant wife at home awaiting his return / Dependent on faith, will she ever learn? / Ignore the consequences have faith in the Lord / Ignorance is bliss until reality sets in / Never wake up again

During live performances, bands would commonly discuss what the songs were about. And at merchandise tables, they sold T-shirts and records along with zines, books, patches and pins, all of which commonly contained political images or slogans.

Some bands became meta-critics of the punk scene itself, encouraging listeners to recognize that punk is about more than music.

In “Preaching to the Converted,” Kill The Man Who Questions critiqued the complaints bands would receive for becoming too preachy at shows:

“Unity” the battle cry / Youth enraged but don’t ask why / They just want it fast and loud, with nothing real to talk about / 18 hours in a dying van / Proud to be your background band.

In West Philadelphia, punks also staffed the local food cooperative and organized activist spaces – like the former A-Space on Baltimore Avenue and LAVA Zone on Lancaster Avenue where groups such as Food Not Bombs and Books Through Bars, among others, would operate. I personally organized a weekend gathering of the Northeastern Anarchist Network at LAVA in 2010.

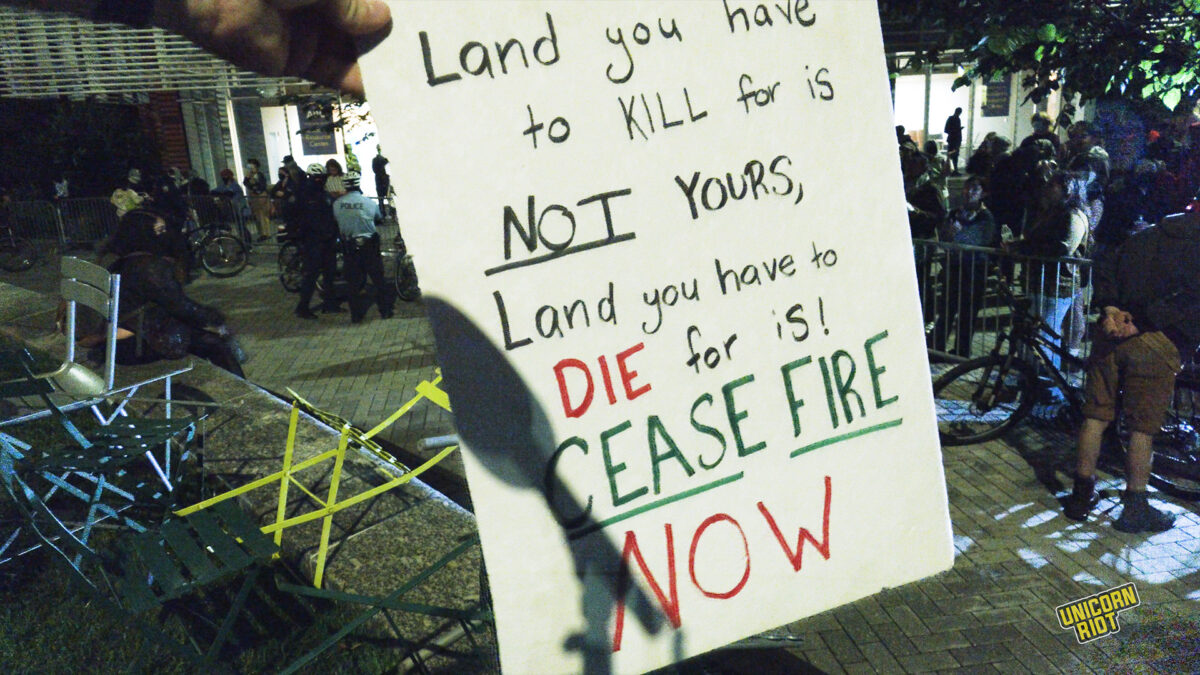

Punks raised money for charities and showed up to local protests against capitalist globalization and countless other causes. At the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia in the summer of 2000, black-clad punks whose faces were hidden behind masks marched in the streets along with an enormous cadre of local community organizations.

Punk not dead in Philly

Since punk’s earliest days, people have bemoaned that “punk is dead.”

In Philadelphia, I’ve seen how the anarcho-punk scene of the 1990s and 2000s has changed, but also how it continues to influence local bands and the values of punk rock broadly.

Many former and current members of the Philly anarcho-punk scene are still activists in various personal and professional ways. Among those I interviewed between 2006 and 2012 were social workers, labor organizers, teachers and professors, and school and drug counselors. For many, their professional lives were influenced by the anarchist ethics they had developed within the punk rock scene.

And many local punks showed up at the Occupy Philly camp and protests outside City Hall in 2011, and later marched in the streets during Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd and killing of Breonna Taylor in 2020. They also participated in the homeless encampment on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, also in 2020. And local punks I know continue to participate in grassroots campaigns like Decarcerate PA.

Anarchism and punk rock open up avenues for disaffected youth – in Philadelphia or anywhere else – to dream of a world without capitalism, coercive authorities, police and all forms of injustice.

In the words of R.A.M.B.O., one of the better known hardcore punk bands of the era and who released their latest Defy Extinction album in 2022: “If I can dream it, then why should I try for anything else?”