from It’s Going Down

Following months of riots, building barricades, and stand-offs with police trying to evict encampments, in late September of 2020, Philadelphia Housing Action was able to claim victory, after the city of Philadelphia offered unsheltered families and individuals access to housing in formerly vacant buildings, a process which people had already begun in the months prior, as homes owned by Philadelphia Housing Authority were squatted. In the end, upwards of 75 homes were handed over by the city, which included many homes which had been previously squatted. Here Philadelphia Housing Action looks back at 2020 with analysis and a timeline on what all went down.

On Sept. 26, housing activists and organizers from Philadelphia Housing Action declared victory after the city agreed to allow 50 previously unhoused families who took over a number of buildings to live in vacant, city-owned housing through a community land trust.

Philadelphia Housing Action has actually been many years in the making; grounded in struggles around gentrification, displacement, homelessness, police violence, institutionalization, family separation, legalized discrimination and more. All of us had been in the city for years if not our entire lives. OccupyPHA had been sweating the Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA) for over five years around it’s rogue private police force and systematic displacement of neighborhoods through forced relocations under threat of eviction, selling of public land to developers, deliberate vacancy and eminent domain. In 2019 OccupyPHA had an encampment in front of the housing authority which lasted over 120 days focusing on these issues that laid a lot of the groundwork for what was to come. The issue of vacant public housing blighting neighborhoods and creating the pretext for eminent domain had long been a concern and the idea of occupying those houses as an act of protest and counter-gentrification had been discussed for at least a year.

Early on in 2020, the group of us who would go on to form Philadelphia Housing Action were finding each other in the same spaces as we challenged the city’s Office of Homeless Services around the ongoing policy of evicting homeless encampments. Like most places, nobody seemed to give a shit about homeless people and attempts to get media coverage or rally allies fell pretty flat. After a while, it became obvious that fighting the city on their terms wasn’t enough, we needed to take direct actions and force the issue; moving people into vacant publicly-owned houses seemed like the best way forward. Once COVID-19 rolled in and people were given stay at home orders, it just seemed like common sense for us to move ahead with take-overs, like a few other groups had already done around the country.

For several months as a small group we worked at that entirely under the radar and managed to occupy around 10 Housing Authority houses, primarily with families numbering a total of 50 people before the city erupted over the murder of George Floyd. Although Philadelphia Housing Action represented members from several groups, there were never more than 5 or 6 of us doing the work, none of us were getting paid and we got all the houses up and running with less than $1,500 from small donations or out of pocket. We had no legal or formal organizational support and relied entirely upon ourselves.

SOURCE: Philadelphia Housing Action

Within 10 days of the George Floyd uprising, we initiated a homeless protest encampment downtown and within the month we had made the announcement about the housing take-overs. Over the course of the summer hundreds of people became engaged in the encampments and the campaign while our group grew smaller, some members breaking away and one dying tragically of an overdose. We ended the year having housed 150-200 people, occupying 30 houses, continuing to fight the city for what we were promised and doing our best to weather the drama that comes after any upswing in mass movement activity inevitably tapers off and devolves into finger-pointing and competition amongst former allies.

We are proud that not a single occupied house was evicted and that there were no arrests in the largest organized and public housing takeover in the United States in more than a generation. We are gladdened that through the protest encampments and occupations the connections between homelessness, housing, and institutional/historical racism were put into much sharper focus while the racialised systems of domination, surveillance and control that permeate the homeless industrial complex, public housing, family court and more were successfully linked to the movement against police and state violence. We are hopeful that our demonstrated ability to link, cross-pollinate and grow movements for tenants rights, homelessness, public housing and foreclosures can be replicated by others across the country, for indeed they share a common enemy. Our campaign victory to win the transfer of vacant city-owned property to a community land trust for low-income housing was a big win for the national movements around housing and human rights and was built upon the shoulders of the many people and movements who came before us both here in Philly and abroad.

It is our assessment that in the year to come, we will see a great deal more in the struggles around housing as a mass eviction wave looms and the economy seems poised to fall off a cliff. We hope that in some small measure, we have done our part to set the stage for the fights to come and inspire others to take the bold and direct actions necessary to keep our communities safe and advance the struggle for universal housing.

Below is an incomplete and summarized timeline of our activities in 2020.

January 6th Philadelphia Housing Action protests encampment eviction at 18th and Vine St/5th and Wood streets along with members of North Philly Food Not Bombs (NPFNB),

February 12 Philadelphia Housing Action attends and contests meeting held by Office of Homeless Services about the coming planned eviction of the encampment at the convention center,

March 23 Philadelphia Housing Action and allies including NPFNB contest eviction of encampment at the convention center on the morning of City’s stay at home order, confronts David Holloman of Homeless Services with newly published CDC guidelines advising against evicting encampments. Later in the afternoon, Philadelphia Housing Action takes its first abandoned PHA property and opens it to the homeless community.

Throughout April and May Philadelphia Housing Action identifies and opens 10 more city owned houses for homeless families while city remains in lockdown.

April 10-17th Philadelphia Housing Action supports first protests/daily actions since lockdown led by no215jails coalition for the mass release of people from jails and prisons.

April 16th Philadelphia Housing Action supports action by No215Jails Coalition at CJC, chases Judge Coyle and her small dog who had denied every single case for release put before her down the street and blocked her exit from the parking garage.

April 17th Philadelphia Housing Action publishes Op-Ed in the Philadelphia Inquirer calling for the opening of empty hotels and dorms for the unhoused during the pandemic.

April 22nd Philadelphia Housing Action / ACTUP informs the City of Philadelphia about federal funding available that would pay for non-congregant housing in the form of Covid Prevention Spaces.

May 5th Philadelphia Housing Action contests encampment sweep on Ionic St w/ members of NPFNB. Delays sweep.

May 13th Philadelphia Housing Action supports ACTUP, ADAPT/DIA, Put People First, DecarceratePA, Philadelphia Community Bail Fund and March on Harrisburg pressing Managing Director Brian Abernathy to open non-congregant housing for people living in shelters, nursing homes and recently released prisoners. Demands universal testing in all congregant housing.

May 27th City of Philadelphia evicts homeless encampment from the international terminal baggage claim. Philadelphia Housing Action had visited the encampment several times throughout may and participated in advocacy work that delayed eviction for over a week due to legal action from Homeless Advocacy Project and attention from the press. First Covid-19 Prevention Hotel is opened in Philadelphia.

May 30th Philadelphia Housing Action joins the largest multi-racial uprising against police violence in the history of the United States in response to the killing of George Floyd. Uprising is city-wide and spills into the surrounding area with a week of street fighting, looting, riots and marches. The National Guard is mobilized to the city and occupies downtown, displacing the homeless population while people continue to loot and blow ATMs.

May 31st Philadelphia Housing Action / ACTUP / Put People First / Global Women’s Strike / March on Harrisburg demonstrate/hold funeral services at the home of Liz Hersh, Managing Director of the Office of Homeless Services.

June 6th OccupyPHA and Philly for REAL Justice lead a march of several hundred from PHA Police Department Headquarters to Temple Police Department Headquarters and back highlighting the impact of unaccountable private police departments on North Philadelphia and their connection to gentrification and displacement.

June 10th Philadelphia Housing Action and homeless activists initiate a protest encampment at 22nd and Benjamin Franklin Parkway under the banner of Housing Now. Encampment defies police orders, declares a no cop zone, bans homeless outreach, issues demands and expands rapidly. In the evening a small march blocks traffic and breaches the outer doors of Mayor Kenney’s apartment complex.

June 15th James Talib Dean, 34, co-founder of the parkway encampment, co-founder of Workers Revolutionary Collective and member of Philadelphia Housing Action dies at his home of an accidental drug overdose. Parkway encampment officially renamed Camp JTD.

June 22nd Marsha Cohen, executive director of Homeless Advocacy Project issues a public apology for her comments to the Philadelphia Inquirer about Philadelphia Housing Action being ‘insane’ and ‘using homeless people as pawns,’ amongst other vaguely classist/racist comments.

June 22nd Occupy PHA/Philadelphia Housing Action makes public announcement about its housing takeovers on independent media outlet Unicorn Riot.

June 23rd Philadelphia Housing Action taps water fountain, runs 1000 feet of pip to install running water, hand wash stations and a shower at CampJTD.

June 26th Philadelphia Housing Action and representatives from Camp JTD meet with city officials in an abandoned storefront. City makes no offer of permanent housing, denies having power over the housing authority or ability to convey other vacant city-owned property.

June 28th Philadelphia Housing Action / OccupyPHA open second encampment on an empty lot across from Housing Authority headquarters on Ridge Ave. The lot, taken through eminent domain by the Housing Authority is slated for of 81 market rate and 17 ‘affordable’ units, along with a parking garage and ‘supermarket.’

June 30th Housing Authority attempts to fence in Ridge Ave encampment and post no trespassing signs. Encampment residents resist, blocking bulldozers and tearing fenceposts out the ground, led by Teddy Munson. Managing Director Abernathy orders Housing Authority to ‘stand down,’ proving that city has power over the Housing Authority. Supporters immediately erect barricades around the entire perimeter of Camp Teddy, working into the night.

July 7th Philadelphia Housing Action taps into city power at CampJTD, installs outlets to power fridges, etc.

July 9th Philadelphia Housing Action breaks off negotiations with the city after several weeks of talks. Cites city’s refusal to offer any actual housing and refusal to bring the Housing Authority to the table.

July 9th PHA Police attempt eviction of occupied house. OccupyPHA/Philadelphia Housing Action and loosely organized Eviction Defense Network rush to the scene and successfully force the police to withdraw before they can enter the building. The house is the first of only 4 to be discovered by the Housing Authority.

July 10th City posts eviction notices for both encampments, cutoff date set for July 17th.

July 13th Philadelphia Housing Action rallies hundreds of supporters at Camp JTD, vowing to resist eviction and demanding permanent housing. Support for the encampment ratchets up all week with allies calling for supporters to sleep over to defend the encampment the night before eviction.

July 13th-17th OccupyPHA and Camp Teddy residents protest at Philadelphia Housing Authority President/CEO Kelvin Jeremiah’s personal home every day.

July 15th City of Philadelphia pressures porta-potty rental company National Rentals to cancel contract with CampJTD. Philadelphia Housing Action supporters cut locks to city bathrooms at Von Colln Field in response.

July 16th City backs down from eviction. Managing Director Brian Abernathy resigns. Mayor Kenney says he will become personally involved in negotiations.

July 20th Philadelphia Housing Action meets in negotiation with Mayor Kenney, other high level city officials as well as the CEO/President of the Philadelphia Housing Authority, Kelvin Jeremiah. OccupyPHA vows to continue occupying houses. PHA carries out raid of long standing land occupation, the North Philadelphia Peace Park, in the middle of negotiations.

July 30th Final meeting with Mayor Kenney.

August 4th Both encampments weather Tropical Storm Isaias.

August 10th Philadelphia Housing Authority holds press event with employees posing as ‘community members’ speaking out against Camp Teddy. OccupyPHA and Camp Teddy residents counter-demonstrate, infiltrate event and get on the microphone.

August 11th Philadelphia Housing Authority announces the creation of a ‘Community Choice Registration Program’ in an effort to appear like it is meeting protest demands.

August 13th Deputy Managing Director Eva Gladstein breaks off negotiations with Philadelphia Housing Action in an email, saying protestors were not meeting the city halfway.

August 16th City posts 24 hour eviction notice for protest encampments.

August 17th Over 400 supporters turn out the morning of eviction to defend the encampments. City Council Members Gauthier and Brooks intervene and re-open talks between the city and the encampments Talks last for over 6 long hours. Lawyer Michael Huff files in Federal court for a restraining order and injunction against eviction, representing individuals from both encampments.

August 17th PHA Police attempt extrajudicial ejectment of occupied house late in the night. OccupyPHA arrives and forces PHA Police to leave mid-ejectment. OccupyPHA demonstrates at PHA CEO Kelvin Jeremiah’s home every day the rest of that week.

August 25th Federal judge rules in favor of the city, clearing the way for an eviction, but mandating 72 hours notice with protections and storage for residents property.

August 31st City issues ‘3rd and Final’ eviction notice set for September 9th.

September 1st Philadelphia Housing Action publishes Op-Ed in Philadelphia Inquirer detailing demand for the transfer of vacant city-owned properties to a land trust for permanent low-income housing. Philadelphia Housing Action meets again with the City despite eviction notice. City and Housing Authority finally admit to having the power to transfer properties to meet the demands, but claim they simply do not want to.

September 3rd Philadelphia Housing Action and encampment residents participate in blockading the reopening of eviction court. The courts are effectively closed down for the morning before protestors are cleared by riot police.

September 4th OccupyPHA and camp teddy occupy a many years vacant, but newly built PHA property around the corner from Camp Teddy. After holding the building for several hours, occupiers foolishly allow access to the PHA Police. PHA finally moves in tenants the same night. In an email, PHA informs OccupyPHA found Jen Bennetch they have requested a federal investigation of her and the housing takeovers under the Riot Act.

September 6th Philadelphia Housing Action, encampment residents and supporters rally and march to Mayor Kenney’s apartment building and hold intersection and rally for hours.

September 8th Whole Foods, Target and CVS board their windows in preparation of encampment eviction and possible riots. OccupyPHA and Camp Teddy visit the homes of senior managers of the Philadelphia Housing Authority.

September 9th In a repeat, roughly 600 supporters turn out to fight the eviction, barricades are massively expanded at Camp JTD, including the closure of N 22nd St next to the encampment. The street remains closed for the rest of the month. City attempts to send Clergy to both encampments in an attempt to persuade people to leave but they are shouted down and leave in humiliation. Although trash trucks and buses are staged on the parkway, police never appear. Both encampments remain in a state of heightened alert over the coming weeks. Police test response time and defenses several times but do not arrive in force.

September 10th supporting organizers at camp JTD invite Mayor Kenney to a brunch on September 14th, raise a banner facing the parkway with the invitation.

September 14th Mayor Kenney declines to attend brunch.

September 18th HUD Mid-Atlantic Regional Office formally confirms that the Philadelphia Housing Authority can legally transfer properties without the need for federal approval.

September 26th Philadelphia Housing Action announces that city has tentatively agreed to transferring 50 vacant houses to a community land trust in return for ending the encampments. City/PHA comments that the announcement of a deal is ‘entirely premature.’ In talks, City had confirmed with Philadelphia Housing Action that they were willing to transfer the houses and continue negotiations in exchange for removal of the 22nd st barricades, a decision ratified by popular assembly of Camp JTD residents after much canvassing and discussion over the next several days.

SOURCE: Twitter @PeoplesParty_US

October 1st Philadelphia Housing Authority proposes settlement with OccupyPHA for resolution of the Camp Teddy encampment. PHA offers 9 fully rehabbed houses, two empty lots, the transfer of any squats that have already been approved for disposition to the land trust, amnesty for all Philadelphia Housing Action squatters, an end to extrajudicial ejectments and evictions by PHA Police, jobs for encampment residents to rehab the houses, a 1 year moratorium on sales of PHA property and an independent study on the impact of PHA property sales, participation of PHA Police Department in City of Philadelphia reform initiatives and to fully implement the CCRP with up to 300 vacant properties.

October 2nd Camp Teddy residents ratify the agreement and OccupyPHA signs agreement to vacate by the night of Monday the 5th.

October 5th Camp Teddy vacates and clears encampment by deadline. PHA informs the City after the fact. City is reportedly furious.

October 8th OccupyPHA founder Jen Bennetch wins a PA Superior Court ruling setting a state precedent affirming the right to film DHS workers (Philly’s version of Child Protective Services) performing their duties. The case originated in 2019 when the Housing Authority and homeless service provider ProjectHOME brought a complaint against Ms Bennetch for having her children with her in the daytime during her 2019 124 day occupation of the PHA headquarters. Ms Bennetch denied DHS workers entry to her home and filmed them in front of her house. In the lower court ruling, the family court Judge Joseph Fernandes had ordered Ms Bennetch to delete and remove from social media all videos of the DHS workers and to never record them again. Ms Bennetch’s appeal to the Superior court was based on First Amendment grounds.

October 10th Managing Director Tumar Alexander approaches OccupyPHA with a ‘best and final’ offer for resolution of Camp JTD in exchange for 50 additional houses.

October 12th After multiple assemblies and extensive canvassing at Camp JTD, Philadelphia Housing Action signs agreement to vacate on a tight timeline in exchange for 50 additional houses. Over the coming weeks Philadelphia Housing Action, supporters, the Housing Authority and the City work to find people housing and clear the encampment.

October 21st A Camp JTD resident legally obtains a unit at the formerly occupied newly constructed vacant PHA property around the corner from Camp Teddy.

October 23rd Marsha Cohen officially resigns as executive director of Homeless Advocacy Project.

October 26th Camp JTD formally closes and is fenced in by the city. Upon closure Philadelphia Housing Action counted 30 occupied city-owned properties. In the final weeks, 35 residents were given rapid re-housing vouchers despite income requirements and 10 elders gained immediate access to PHA senior housing. Philadelphia Housing Action estimates that more than 200 people gained access to housing over the course of the encampment through housing occupations or various city/housing authority programs.

October 26th Philadelphia Police shoot and kill Walter Wallace Jr, sparking widespread riots.

October 29 November 1st OccupyPHA/Philadelphia Housing Action demonstrate nightly at Council President Darrell Clarke’s home forcing a meeting with OccupyPHA and allies on November 4th. The following week the Philadelphia Housing Authority confirms Clarke has dropped his opposition to Philadelphia Housing Action getting houses in North Philadelphia. By November 23rd Darrell Clarke procedurally kills his own initiative to give $14.5m to the Philadelphia Police Department and refuses to comment to the press.

November 11th Philadelphia Housing Action occupies lobby of 22nd district for several hours after receiving the MOU between Philadelphia Police Department and Temple Police Departments. MOU is read out loud clarifying the limits of Temple University Police jurisdiction and generally harassing the police working that night, a turkey was thrown across the lobby.

December 1st Philadelphia Housing Action visits Covid Prevention Site Hotels and occupies lobby, confronts security.

December 2nd Philadelphia Housing Action has call with Office of Homeless Services and hotel residents about impending closure of Covid Prevention Hotels on Dec 15th. Demands delay of closure and extension of program. Over the coming weeks it is revealed the city will be moving residents from the hotel into former halfway houses that do not have private rooms or bathrooms. Philadelphia Housing Action continues to organize with residents and other advocates for the permanent housing the city promised at the beginning of the program. Activity is ongoing.

December 23rd Philadelphia Housing Action successfully pressures PHA to get gas turned on to several properties that were being denied service by PGW. City moves first residents from prevention hotels to former halfway houses and Philadelphia Housing Action learns that the new facilities have no heat or hot water. Philadelphia Housing Action and supporters visit the home of Office of Homeless Services Director Liz Hersh at night, talking to neighbors and playing loud music to protest the closure of the Prevention Hotel and the placement of people with preexisting health conditions into congregant housing with no heat or hot water over the holiday.

December 28th Philadelphia Housing Action visits Walker Hall, the former halfway house owned by private prison contractor CoreCivic that is now housing residents from the Covid Prevention Hotels. Security denies access to the premises and calls the police. The location is in a remote industrial area and lacking services, transportation or access to food. Heat and Hot water are still not available to all residents, nor are they allowed to possess space heaters. Residents have windows in their doors and are not permitted to block them. Female residents complain about male guards looking into their rooms. No transportation was made available. Residents are searched upon entry and at least one resident, a disabled elder, has been expelled for possession of a marijuana cigarette.

January 1st Philadelphia Housing Action, pushing for corrections around the availability of federal funding in a Philadelphia Inquirer article on the closure of the Covid Prevention Hotels is able to confirm that the City of Philadelphia never applied to FEMA for funding that would pay 75% of the program costs of the program. The statement from a city official on record undermines the entire premise of closing the hotel due to a lack of funding and exposes a high level of willful incompetence at the Office of Homeless Services. Furthermore, Philadelphia Housing Action and ACTUP are able to confirm that the current facilities will not be eligible for FEMA funding due to their congregant nature.

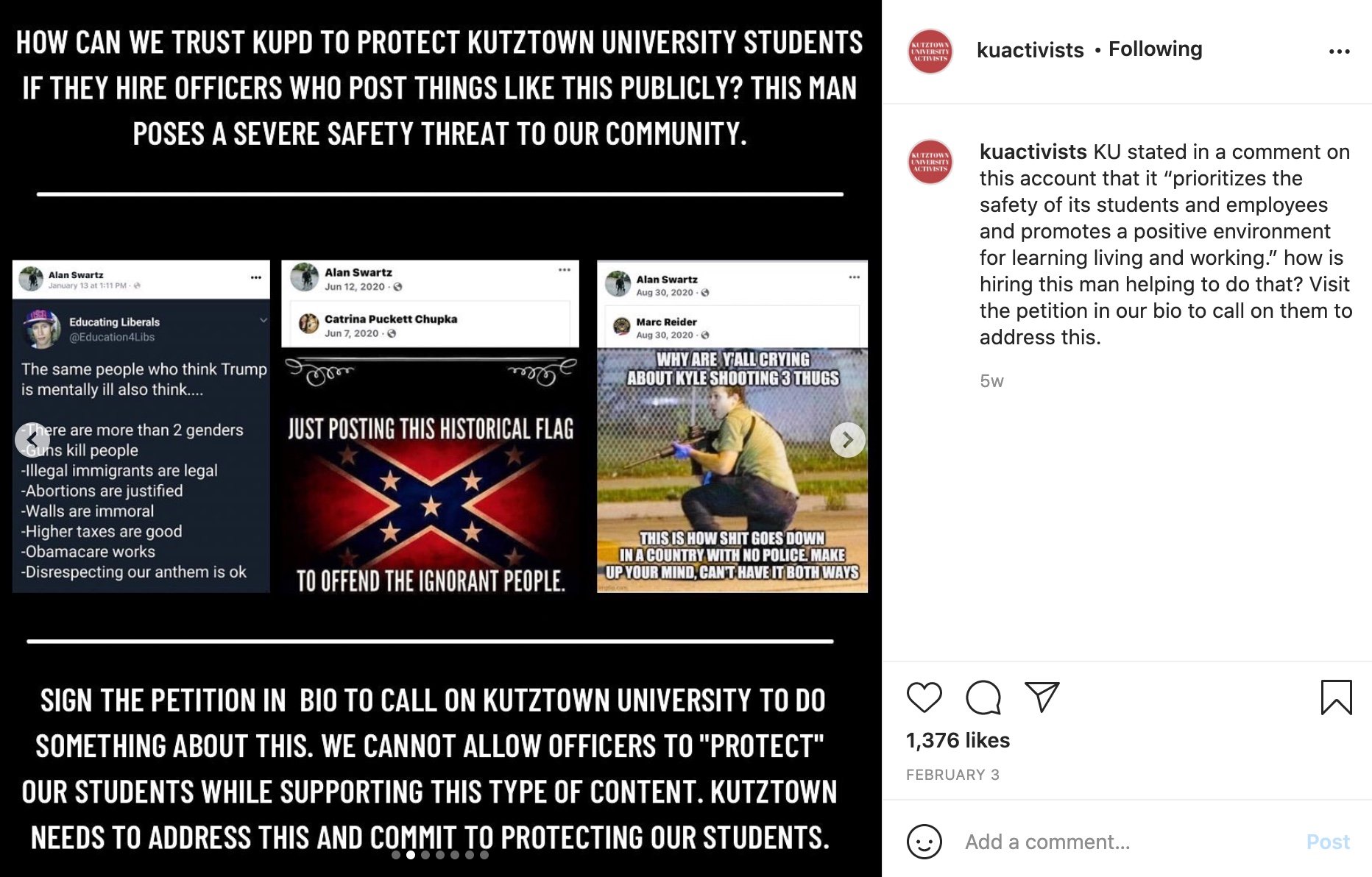

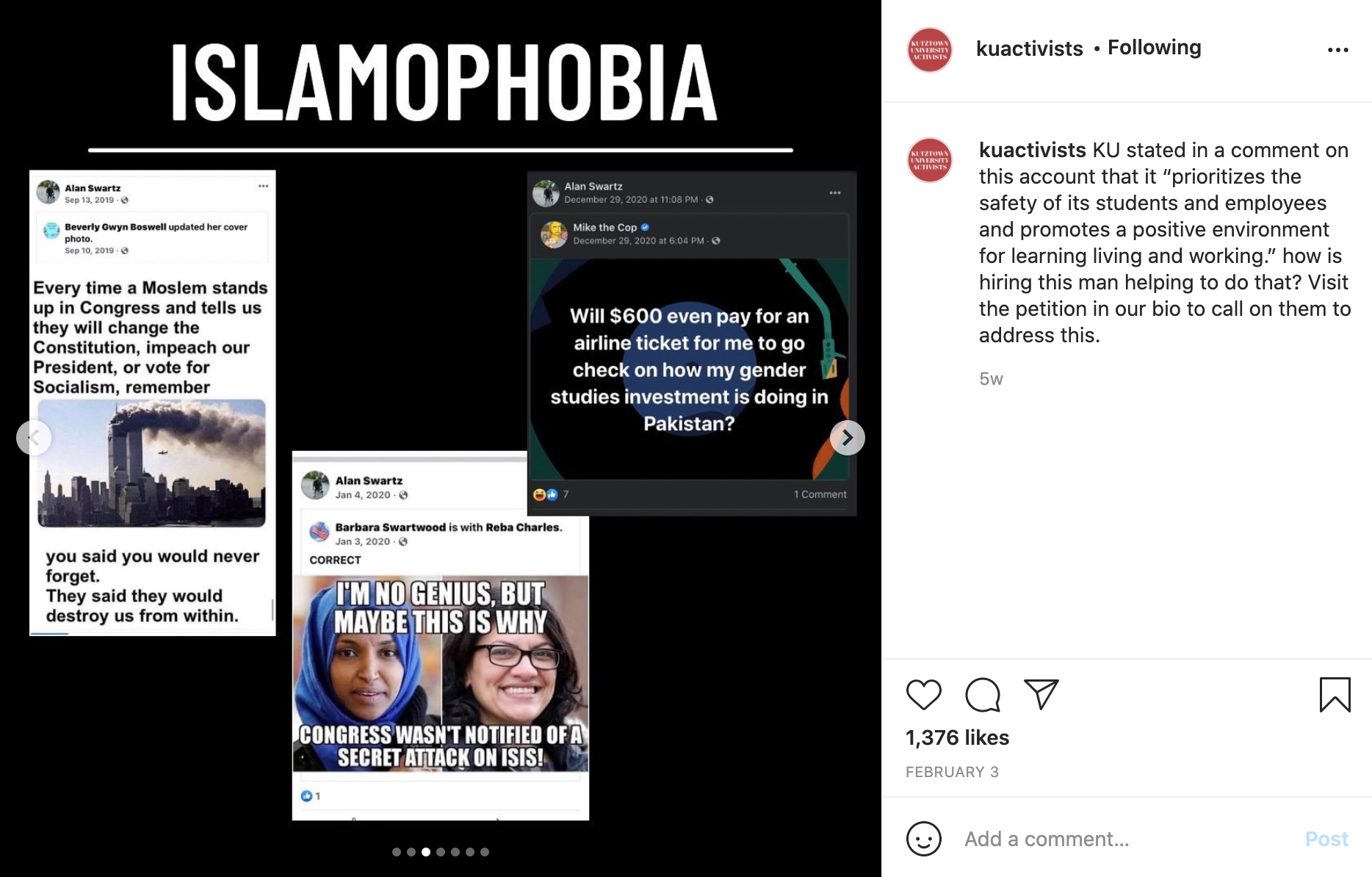

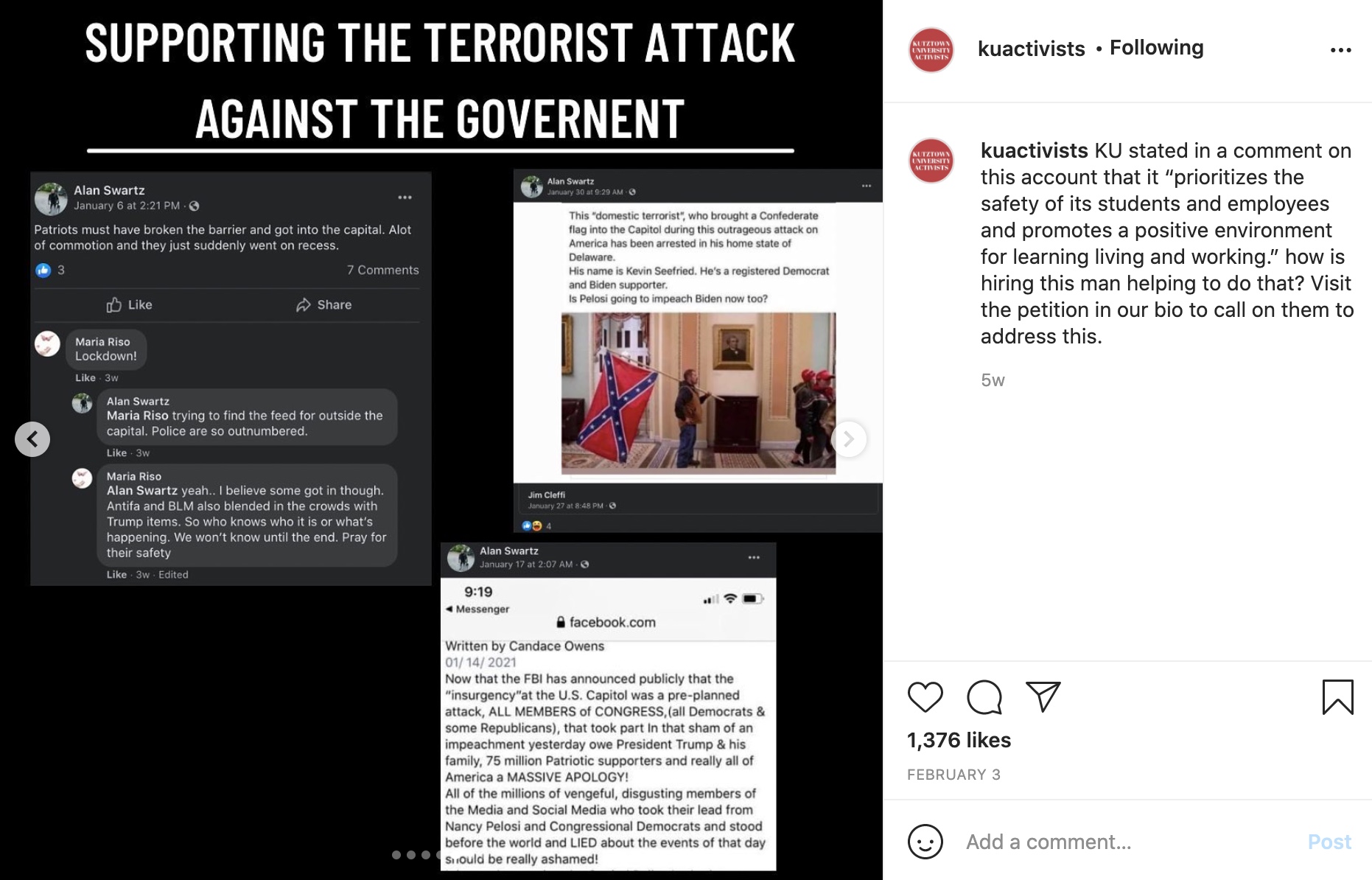

Alan Swartz, a Bigot in Kutztown University’s Police Department

Alan Swartz, a Bigot in Kutztown University’s Police Department