from Scribd

PhillySprayWatch2020: Open Source Graffiti + Street Art Whitepaper

There’s Nothing Left but the Streets

from Rampant

George Ciccariello-Maher interviewed by brian bean

The recent rebellion in Philly against the police murder of Walter Wallace Jr. is rooted in struggles of the past and reflects the uprisings of the future.

This summer we took part in a rebellion across the country against racism and police brutality. Now, the nationwide scope of protest has diminished. However, since then we’ve seen more localized rebellions in Kenosha, and Chicago around the shooting of Latrell Allen, and around the release of the video in Rochester. Philly is the most recent. In that context, what’s going on with Philly?

The past weeks in Philly we have seen pretty significant rebellions around the police murder of Walter Wallace, about five blocks west of where I join you from. It’s important to understand that Philadelphia saw some of the most militant reactions nationwide to the killing of George Floyd. There was mass rebellion in Philadelphia that lasted several days and in June the National Guard was here.

This all takes place in the backdrop of a much longer shift in radical politics in the city, which goes back to around 2015, though it’s also bound up with much longer trajectory. We’re talking about a small group of organizers who were out there trying to raise hell around the police killing of Brandon Tate-Brown in late 2014 and 2015. As Ferguson and Baltimore were popping off we in Philly were struggling over this one particular case.

The militancy of those struggles, even if they were relatively small scale, really broke open the city, which has been a city of long-term resistance, a city in which Black struggles have been crucial, in which brutality and mass murder by the police, like in the case of the MOVE bombing, have been essential to understanding the political context.

In a way, Philly was primed to respond to the killing of George Floyd, and it did. I’ve never seen anything like what we saw in Philly on May 30th and into June. Not even during the Oscar Grant rebellions in Oakland—which was where I cut my teeth politically—did I see that scale of rebellion, looting, and mass resistance.

Now what’s happening today is interesting because it’s obviously more localized. We’re seeing a city and a population that’s really just had enough, that has a level of clarity around what the police do, that knows perfectly well that we don’t need to even entertain the lies about “Did he have a knife?” or that the police were just trying to do their job and keep people safe. We know that’s not true.

We know that police are trained cowards, who are taught from day one to put their life above anyone else’s life. This is why they shot and killed Walter Wallace. He was on a block full of people—neighbors, family members, none of them were trying to kill him because they didn’t think he was that big of a risk to their well-being. It was the police who decided to kill him, to fire fourteen shots.

We know that police are trained cowards.

You are seeing in the city that people just don’t buy the bullshit anymore, and they’re buying it less and less by the day. While the first night of protest we saw that the police were restrained by the police commissioner, who took a political beating back in June over the use of force, the use of teargas, rubber bullets, and extreme levels of brutality, they weren’t going be held back forever. They came back on the second night and really just beat the piss out of people for fun, because this is what the pigs do.

They thought they would get away with it like they always get away with it. But, as you probably have seen, there’s now a viral video of them smashing the windows out of a car, beating the passengers, and tearing a two-year-old child out of the arms of his mother. They then tried to take credit for rescuing him, saying that he was found wandering barefoot, which is an absolute lie. And then everyone saw the truth revealed, which is further confirmation of the embarrassment that the police represent, and that they are really just lying thugs who are out to protect themselves and no one else.

This, as a lot of other people have pointed out, is a deeply white supremacist and colonial idea that says: “The people that I’m brutalizing, I’m actually rescuing them. This baby whose windows I smashed out, who I stole away from his mother, I’m actually here to protect him.”

This is the veneer that policing has always had. No matter how bad the violence that is inflicted by the police on communities, they’re told they just need more police, and the police are really there to protect them. Policing is a form of psychological and physical abuse. And people really are just not buying it anymore.

What do you think has led to that level of clarity? I ask because in varying ways around the country, we’ve seen a shift towards people talking about defunding and even abolishing the police, seeing the institution as a problem in itself, not as something to reform. So in Philly, like you said, people have had enough and there’s this clarity. What do you think has led to that? Is it the ongoing organizing? Is it the national radicalization? Is it just people seeing it?

The first thing is that we live in a moment of global revolt and rebellion. This has been going on for well over a decade in the United States. I think the uprisings in Oakland in 2009 really helped kick things off, the Occupy movement followed just a couple years later, Black Lives Matter a couple years after that. You have this escalating spiral of struggles across the country, pin-balling around, and people are becoming more radical and they’re developing a better understanding of theory and seeing more of the way that theory plays out in practice.

They’re seeing that they have power in the streets, they’re seeing that struggles lead to actual change and transformation. This is all the context of what we now see occurring amid a devastating economic crisis and the continued impoverishment of not only poor communities of color, but also the indebtedness of students and the absence of a horizon of how to get out of this situation. This is the generation leading the George Floyd revolts, who are nineteen, twenty, twenty-one years old. They have grown up with nothing but Black death at the hands of police, economic crisis, no options, and no future. The fact that they are rebelling should not surprise us.

These spirals of struggle move across the country, radicalize here and there, and bring us up to the level that we’ve reached. You can see this in the words of Kandace Montgomery, an abolitionist organizer with the Black Visions Collective in Minneapolis who said: “In 2015 [when Jamar Clarke was killed] . . . we were clear about the problem. Now we are clear about the solution.” This is why you have this really astounding uniformity of calls to abolish, or at the very least defund, the police. These calls are not brand new—they’ve been emerging over the past few years, but the fact that this is what people are reaching for in this moment of struggle says a lot about the level of consciousness that’s developed over the past ten years.

We just had a national presidential election that offered a choice between an openly racist president and a more veiled racist vice president in Joe Biden, who campaigned on a law and order, shoot-them-in-the leg version of police reform. So those are the choices, and there’s rebellion in Philadelphia where there’s still a National Guard presence and where the Democratic mayor only just lifted a curfew. What does all this say about the current political situation and context both in Philly and nationally?

When Gramsci talks about a time of monsters, this is what he’s talking about. While I’m not even a Bernie stan, it’s clear that we could have had a Bernie. Instead, who do we get in the context of mass, nationwide anti-police rebellion? A segregationist and a cop. This was the Democratic ticket.

This is a time of monsters because it’s a moment in which we know which way history is pointing, but on some level that path is blocked. Now, while it’s blocked on the level of formal politics, it’s not blocked in the streets. In the streets, things are moving forward by leaps and bounds, and I think that’s precisely what matters.

These struggles will explode no matter who is in power. There are ways that having Trump in power sets off struggles by drawing more left-liberals into struggle and radicalizing them to play a crucial role in a growing coalition of resistance. But there are ways that when Obama was in power, for example, we had the eruption of Black Lives Matter because of the dashed hopes and the crushed expectations. Nothing is going to change under Joe Biden; nothing would really change under Donald Trump. So that collision with reality has a shocking and radicalizing effect on people who realize that there’s nothing left but the streets.

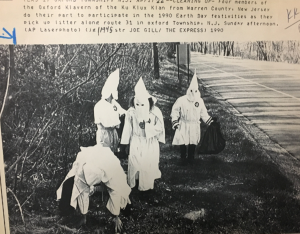

We know that in 2021, police murder is going to be the story, and we know that because it is an old story. If you look at the history of mass resistance in this country, that resistance is almost always driven by Black and brown people, almost always against the police, almost always sparked by police murder. Why? Because the police are founded on that great betrayal of the Black struggle by poor whites at the end of slavery, those who chose the Klan instead of multiracial equality. Instead of abolition-democracy, they opted for white terror.

So we should not be surprised that now, more than 150 years later, we’re looking at the same forces playing out in the same way, because these are historical questions that we haven’t yet dealt with.

You mentioned a continuity of organizing in Philly. What would you say about the connection between what’s going on currently and the struggle around MOVE? Of course, the MOVE house was about four blocks from the shooting of Walter Wallace.

The MOVE struggle and the struggle around Mumia, not to mention other struggles like the struggle for freedom for Russell Maroon Shoatz, are essential to understanding the political landscape in Philadelphia. They’ve provided it with a radical backbone that leans toward two opposing poles. One is a level of kind of mass fear. It was just in 1985 when the City of Philadelphia dropped a bomb on West Philly, killed scores of people, and burned down the city block. That’s not that long ago; everyone remembers it. Even when I moved to Philly a decade ago and started organizing, people were like, “Thank you for doing this, this is amazing. But you’re all gonna get yourselves killed.” That fear is deeply embedded in the psyche. At the same time the recognition of what the police in the city actually stand for is undeniable.

And so you have a situation that gives rise to a willingness to engage in mass resistance. There are lots of material dynamics that play into this: who’s in charge, how it’s played out, and the way that these struggles are able to coalesce. You can see an escalating spiral beginning with struggles around Brandon Tate-Brown, in which small groups of people were constantly in the streets, constantly confronting the police commissioner. Bear in mind that this was Charles Ramsey, Obama’s top cop, the person in charge of the twenty-first-century policing reform report, who advocated civilian oversight and transparency but wouldn’t even tell us who killed Brandon Tate-Brown, who wouldn’t even give us that basic level information, wouldn’t release the video until we fought in the streets to get that, and until we frankly embarrassed him.

These are the cycles, the spirals of struggle. Around the same time, we had a solidarity rally with the Baltimore rebellion. That was the biggest thing Philly had seen in a decade. Thousands of people showed up, took over the streets, blocked the highway, and fought the police. They realized that what’s happening in Baltimore was exactly the same thing, essentially it is Philly’s twin city, and so we see it happen here, we see it happen there.

There were Black cops in 1890 and it didn’t make a difference.

The years since have seen just a consistency to this struggle, not just for demands for a better way of living and for equality, but a struggle against this consistency of police brutality. Philly, we should bear in mind, is a place that had an integrated police force in the 1890s. Du Bois wrote about this. There were Black cops in 1890 and it didn’t make a difference. There was so-called community policing in the 1940s and 1950s, and it didn’t make a difference.

I feel the realization that radical change is necessary is deeply embedded in the psyche of the city of Philadelphia.

So one of the strategic orientations that came out of the past wave of Black Lives Matter organizing is electing progressive prosecutors. Philly has Larry Krasner, who I think is considered one of the best examples of that. What is Krasner doing in this current rebellion and how has he oriented himself?

Absolutely nothing. Dead silence. I think it’s not hard to figure out why Larry Krasner won’t say anything about this until after the election. And even then, I’m not sure what he will say. He’s been very willing in recent weeks to assume a radical anti-Trump stance and to say he’ll prosecute people who show up at the polls to intimidate voters, and that’s fine. But there’s been dead silence on Walter Wallace. I say this as someone who’s pretty balanced in the sense that I think it’s good thing that Larry Krasner is in the DA’s office. We’ve seen hundreds if not thousands of people not sitting in jail as a result of that election, and we’ve seen important experiments in diversion and other strategies for keeping people out of prison, for not arresting people for certain crimes, and for decriminalization. These things are hugely important.

On the material level of movements, it’s been crucially important that, for example, when Occupy ICE was happening, all the people who were arrested were released within two hours with only citations. This is materially important for our movements and has made a huge difference. So I don’t think it’s about denouncing the district attorney. Though Krasner is also someone who’s sending people to jail and who’s not taking a strong enough position when it comes to people like Mumia. What we need to be thinking about is how to operate in a context in which things are getting easier in a certain way, but when it comes to the George Floyd rebellions, for example, the district attorney’s office is insisting on drawing a hard line between protestors and looters and prosecuting looters and releasing protestors. This is a division that, especially if we care about class unity and the unity of this class struggle, we have to refuse 100 percent.

But I think the question is less do we like or dislike Larry Krasner than it is: what does his presence in the DA’s office mean for people? Moving forward we need to push to have all charges dropped from May and June, and there may be some leverage for that after the presidential election.

Looting in Philly and elsewhere, like in Chicago, has been a major, divisive political question in which liberals want to divide the “good protestors” from the “bad protestors”, and people want to say, “Oh, that’s not the protest.” We at Rampant have written about this quite a bit as far as the viability and necessity of defending looting as a political tactic. What do you think the left should say around this specific question and what’s at stake?

I think a lot is at stake. The first thing I’ll say is the same thing I would say around debates around property destruction and violence in general as a tactic. There are certain people who approach social movements on the assumption that if they don’t want these tactics and they win the argument about them they’ll go away.

The reality is people are going to loot. In moments of mass uprising people are going to take things. We are obligated to start from an understanding that that’s going to happen regardless. It’s not like we can make it go away. And yet there are those people who say, “Well, looting makes us look really bad.” Well no, once we start from the understanding that it’s inevitable, a force of nature, you realize that what makes you look bad is not looting. What makes it look bad is losing an argument about whether or not this is something that should happen.

What makes it look bad is when people within the movement are denouncing other people for looting. This is what makes us lose these debates. However, if people stood together and said, “You know what? We’re not going to criticize people who are engaged in certain tactics during these moments of mass uprising in which our concern is the murder of this Black man.” And at that point, the debate goes away. The media of course will still run with it, and they’ll try to discredit people and the movement, but it doesn’t have the same effect.

People are managing the narrative pretty well in the movements now where people are correctly pointing out that Walmart doesn’t belong to us, Best Buy doesn’t belong to us. These big box stores are part of an oppressive capitalist system, and we know that they are stealing from us and stealing people’s labor every day. We shouldn’t give a shit about whether or not they’re looted and could even say that the direct redistribution of goods from them is probably a good thing in this context, under a pandemic, when people are not working and can’t access those things.

The debate does get a little more complex on 52nd Street, two blocks away from here, where some small stores were looted. If you ask people on the block, you hear very different opinions. On one hand, that’s a neighborhood store, it’s owned by this or that person. On the other hand, people will say, “I don’t know who that person is. I know that they racially profile me when I go in there.” And people will ask if those resources are really being dedicated to the community? These are complicated debates.

But the idea that there’s a uniform response to those debates within poor communities of color is just not true. What needs to happen and what does happen are people negotiating these questions in the streets and within movements, when people, for example, try to alert people to locations that should be left alone.

You know, there was an Indigenous youth center in Minneapolis that got smashed up during the rebellions. That didn’t lead people to denounce the looters, but it did lead to them to say, “No, let’s not do this. We’ll have a fundraiser,” and the America Indian Movement engaged in community patrols to help keep an eye on people’s safety.

Dealing with these things within movements is possible and necessary. But the main danger of course—that’s being actively stoked by the police, by the state, and its spokespeople—is that it is used to divide the movement. This has been incredibly dangerous, and in some cases, very effective.

You talked about the radicalization and cycles of resistance moving in leaps and bounds, particularly now. What do you see as the next jump? What’s the way forward, and what do we have to do?

These struggles have been, as everyone knows, popping off everywhere. One of the defining features of the George Floyd rebellions was their contagious ability to spread to the point where we see statues of colonizers being torn down in England as a result. One thing that is undeniably true about the history of Black struggles against the police in the United States is that you don’t know what’s going to set it off. There are all these structural reasons why this was a tinderbox ready to explode. But you never know when the explosion’s going to happen.

It’s going to be an incredibly dangerous time as the old world dies.

We do know that the powder and the spark are even more available today. In January when Joe Biden is in office he’s not going to do a fucking thing to change this deep-seated reality. We know that the history of police reform is the history of reforming the image of the police, not what they actually do. And we know that there is no way to reform away the actual function of the police, which is a repressive, brutal function. That is inevitable, and under this system it’s going to continue.

This continuity is the backdrop to a situation in which people’s lives aren’t getting better, in which there’s a continuing pandemic, and the economic crisis is deepening. People are ready to go at the drop of a hat. We’re going to see an escalation of these struggles, and that’s a good thing.

We also know that the far right is going to be engaging in organized and sporadic violence. It’s going to be an incredibly dangerous time as the old world dies.

October pt. II: Political Naivete

from Viscera

Join us on Friday, October 30th for our next anarchist bazaar and reading discussion. We’ll be celebrating the beginning of Halloween weekend with a discussion of the essay Political Naivete by Aragorn! We’ll be meeting in Rittenhouse Square from 6 pm – 7:30 pm to enjoy each others’ company at the beginning of Halloween weekend and in anticipation of the excitement of the next month(s).

Below is the essay in full. Read some of the related texts, if you dare!

Philly Proud Boys Rally With North Carolina Proud Boys, American Guard

from It’s Going Down

[This post only contains information relevant to Philadelphia and the surrounding area, to read the entire article follow the above link.]

One week after being humiliated at their own rally in Clark Park, where hundreds of counter-protesters gathered to face the fewer than five Proud Boys who managed to turn up for the rally. The Proud Boys who did show up were immediately identified by antifascist researchers, though they attempted to intimidate anti-racist protesters, threatening to dox them and stalking researcher Gwen Snyder’s house, where antifascists had posted guards.

The Philadelphia Proud Boys, led by President Zach Rehl, were joined by members of the North Carolina Proud Boys, as well as Brien James, founder of the Vinlanders Social Club, Outlaw Hammerskins, and the American Guard. James is also a former member of the Ku-Klux-Klan.

This represents an escalation for the Philadelphia Proud Boys. Prior to the summer of 2020, Rehl refused to publicly identify himself as a Proud Boy, telling the Philadelphia Inquirer in 2018 that a Proud Boys rally he organized was simply the members of a Facebook group, “Sports, Beer, and Politics.”

In the Spring of 2019, Rehl was among a group of Proud Boys, American Guard, and militia members who attempted to organize a string of violent rallies across the northeast, trading pictures of the weapons they planned to bring and the specific leftist activists they wished to assault at the rallies. However, the group was stymied when their chats were leaked and the members were doxxed, and the rallies were cancelled.

October anarchist bazaar and reading discussion

from Viscera

Enjoy some much-needed and rarely gotten face-to-face time with other anarchists on Saturday, October 3rd as we gather for a discussion of the essay Social War, Antisocial Tension by Josep Gardenyes.

When an old lady marches in a protest and imagines the street free of cars and full of gardens; when a young boy lights fire to a shopping center that he and his friends have filled with gas cans and imagines a forest growing out of the ruins; when a mother entertains the fantasy of conducting her own birthing with friends in a free community where her daughter will never know of prison, of marriage, of advertising that assaults her self-esteem, of pollution, of institutional education; when all those worlds flourish parallel to our own, we will be stronger than ever.

We’ll be meeting in Clark Park again, this time at the dog bowl – discussion starts at 1:15, come around 1 for social time. As usual, we’ll have some books and pamphlets for viewing and purchase.

Anathema Volume 6 Issue 6

from Anathema

Volume 6 Issue 6 (PDF for reading 8.5 x 11)

Volume 6 Issue 6 (PDF for printing 11 x 17)

In this issue:

- Black August

- What Went Down

- New Projects

- What Next?

- Repression Updates

- Die-Off Debate

- DIY Defunding

- Back to School

- PSL, Occupations, & Some Better Possibilities

August Anarchist bazaar and reading discussion

from Viscera

Join us for our first incision into Philly with a reading discussion and social time in person (!) in Clark Park (tentatively) on the last Sunday in August!

Discussion starts at 1:30 with some hangout time beforehand, we’ll also have some books and pamphlets on hand for sale.

This month’s reading will be Monsieur Dupont’s “Your face is so mysteriously kind,” which you can find on the anarchist library here.

We look forward to seeing all of your mysteriously kind, masked faces! See you there!

interview

Submission

At the beginning of the summer some Philly anarchists were interviewed by some German comrades regarding recent events in the States. This is the transcript of that interview.

How do you explain that the riots and social unrest spread and

intensified so fast in the last month? Do you think the lockdown had an influence on it?

0: I think that coronavirus had a lot to do with it. Before corona people around the world were in revolt and the US was just watching. Hong Kong and Chile and Canada seemed to be going off and people were paying attention to that and learning and talking about it. When the pandemic hit people here lost a lot of work and there was not as much for anyone to do. The protests and riots were a much appreciated break from the quarantine, people got to finally go outside and be together after months, and it was more accessible than if everyone had to be at work.

In other circumstances people would be tied up in work, school, and a larger social life. When the uprising started there weren’t too many places you could be, you could stay home, go for a walk, or go to a riot or protest.

X: I agree, and also think the tension has been building up for some time; and I mean that in a bigger sense than the usual upheaval as pressure release. Many have said that these have been the biggest riots in the States since Martin Luther King Jr was assassinated in the 60’s – so I think in addition to the obvious white supremacy, and the stagnation and poverty under quarantine, there is a growing existential dread from the very real threats of global pandemics, climate catastrophe, fascist terror, rape culture, and many other such things that similarly propelled those global revolts several months ago.

&: Yes, I agree coronavirus was part of the building up. It was a strange, nonlinear build up where many people spent the weeks before trying to figure out how to adapt to isolation and social distancing. Under normal circumstances, you can fantasize about what you would do when the time came to rebel and even speculate about likely time to act. For me, anyway, the virus creates circumstances where it was almost impossible to imagine regularly leaving the house, let alone taking the streets. The virus laid the groundwork for some of the conditions of the riots, creating almost strike-like conditions. But at the same time, there was no clear path to take advantage of them. On the one hand, I think this meant that the activist organizers were not immediately positioned to channel the events in Minneapolis into an ongoing campaign or strategy – allowing for better conditions for a riot. On the other hand, when people watched the news coming out of Minneapolis from their “pods,” they saw these massive self-organized crowds as if they were seeing them for the first time. The sudden, renewed ability to imagine being in the streets together was like realizing how thirsty you are when someone offers you a drink.

It didn’t hurt that, once everyone met up in the streets, many of them were wearing masks. The riot happened right around the time that masks became a normal precaution. Wearing masks took a while to catch on and then kind of went out of style once it got really hot. I hope it gets normalized again.

How was the experience in your local context?

0: In Philly things went wild the last Saturday of May. Center City had intense rioting and looting. People set fire to police cars and stores, fought with the police, and broke into and took merchandise from so many stores. Graffiti against the police was everywhere and many banks were smashed. That night and the next day the rioting spread to other neighborhoods. Stores and malls around the city were looted for the next few days and nights. 52nd St – a main commercial street in West Philadelphia – was the site of clashes with the cops and looting. After that the National Guard came to the city and things slowed down some. There are still protests everyday all over the city but they are calmer and less combative than the first weekend.

Other struggles also escalated briefly while the rioting happened. A labor struggle at a cafe in West Philadelphia was intensified when the cafe was vandalized multiple times and had to end up closing. Gentrifiers in West and South Philly were attacked during the nights immediately following the riots. Mutual aid projects related to homelessness and coronavirus continued while shifting their attention to the uprising.

Housing and homelessness related organizing has seen a big escalation. On one hand a tent camp has been set up right outside of Center City and is growing everyday. On the other hand individuals and families are squatting in city owned properties as a reaction to corruption in the Philadelphia Housing Authority. Both the camp and the squatters are asking for permanent low income housing. This kind of thing would have seemed much more difficult without the context of the uprising.

X: Yeah, there were a few wildcat strikes happening at different businesses that seemed to fit into the slow reduction of combativeness, with at least one still happening. The farther we get from the initial rupture, for that matter, the smaller and more trivial noted actions become.

&: In a similar vein, healthcare workers, anarchists and others tried to occupy an abandoned hospital the other day. It was to be an occupation of the exterior of the building and provide a free clinic. The Hahnemann hospital notoriously remained closed during the pandemic because the investment banker who owns it refused to rent it for an affordable price. The demonstration was more aggressive than most pre-riot demonstrations: the crowd shouted anti-police chants and barricades were rapidly set up to block police in the street leading to the hospital. However, the turn out was much smaller than expected and the police response came swiftly. The occupation was abandoned before the riot police got into formation. So, there are continued attempts at escalation even while crowds are dwindling.

You think anarchists were ready (analytically and materially) and could seize occasions to escalate the revolt?

0: I think many anarchists were surprised at the speed and intensity of the revolt. Many anarchists participated and brought their special knowledge and skills to the table, but I do not think that anarchists were the ones escalating the revolt for the most part. Anarchists out during the revolt were fighting and rioting shoulder to shoulder with other people, many of whom were much more prepared to escalate the situation than anarchists were.

X: We were in the mix, sharing some practical on-the-ground skills, but to some degree I think we were just chasing the intensity. I agree we largely weren’t the ones escalating the revolt, and in fact some participants seemed distrustful of us. There’s also not much of a culture of rioting here, in part because of the whitewashing of history that we’ve long contested, but we don’t have enough of a reach for that to make a significant impact. I think those combination of things, too, meant we weren’t always thinking strategically about our strengths or the state’s weaknesses – though again, in the grand scheme of things, this wouldn’t necessarily prolong the revolt nor significantly weaken our opponents.

&: Yes, I agree. The riot unfolded in a way that exceeded many anarchists’ skills and experience, including my own. At first, the major demonstration followed a familiar – if unforeseen – pattern: a large march made it possible for small groups to fight police and destroy cop cars. I was actually surprised by the amount of cop cars burned and the number of people taking part. At the same time, it was the kind of action – a combination of march and riot – that anarchists are known for in America. It is impossible to say if anarchists were responsible for some of the initial escalations during the demonstrations. What’s clear is that the riots quickly became too decentralized for any one group to be at the center. The looting began, to my knowledge, in the streets near the initial demonstration. But once it began there was a proliferation of flashpoints. It was sometimes difficult to find out where things were happening and, for some time, things were happening at multiple sites at once. The riots took on a shape unlike anything I had been in before.

What forms of recuperation are used and by which actors? And are they successful to channel the uprising back into reformist/democratic discourses?

0: The police and activists sympathetic to them were seen kneeling during demonstrations, a symbolic gesture against police brutality. Many liberals and people on the left are using the popular dissatisfaction to advocate for voting, as though a new politician will change the police. Less often but still present are families of some of the victims of those killed by this racist society who ask that the police investigate and bring to justice the killers.

More insidiously there is a recuperation that masks itself as anti-racism. There are people (black and not) who urge white and non-black people to follow black leadership. The black leadership these people are talking about is always more conservative than the uprising itself. The leadership is always moderate, riotous youth or black revolutionaries are of course never referred to as leadership by these people. This kind of narrative is effective at stopping people who would otherwise take radical or combative action (alongside black people who are already doing the same) by pushing them to feel guilty for not obeying the wishes of black moderates.

&: Not only are riotous youth and black revolutionaries not considered “leadership,” they have been intentionally excluded from the narrative. One way this happens is by replacing them in the narrative with agent provocateurs. Every time something gets broken, burned, or out of control, there’s a corresponding movement to blame it all on agents, provocateurs, outside forces etc. This is in some ways a strategy of recuperation since it seems to be motivated by the desire to separate these bad actors from the respectable protests and their demands. Yet, it’s not exactly a strategy since the there really isn’t a fully-formed activist strategy to recuperate the riots yet. Instead, this attempt to recuperate recent events treats the rioters as a confusing mish-mash of conspiracies. These conspiracy theories stand in for the absent recuperation strategy. Conspiracy theories are spread by a variety of actors–they are not a cohesive group. They are a reserve army of a yet-to-be-initiated activist campaign.

What role play abolitionist ideas (to abolish the police, prisons, etc.) ideas that may be in favor of riots since they bring a topic into focus but at the end of the day pursue a /political/ goal? Is there also a discourse (on the street) around destruction of all power structures?

0: Abolitionist ideas have played a strong role in the uprising. Although the initial cry rang out as “fuck 12” it was quickly turned to “defund/disempower/disband/abolish the police”. Many of the abolitionists imagine on one hand asking people around them to pick up strategies for dealing with life without the police (transformative justice, not snitching, bringing in social workers, etc) and on the other hand asking the government and institutions to disempower police (less money for police, no police in schools, less equipment for police, etc). Many abolitionists understand the rage of people attacking the police but do not imagine that people will remove police themselves and rely on making demands.

Much of the graffiti that came out of the revolt was more pointedly for the destruction of the police. Slogans like “fuck 12,” “acab,” “kill cops,” and “fuck the police,” were all over the walls. The people who push to destroy as opposed to abolish the cops are less present in the discourse but were very present in the street during the rioting. The anarchists continue to push an anti-police anti-prison narrative via a recent noise demonstration outside a prison and via posters and graffiti.

What does it mean that individuals or groups be they militias, gangs or maybe even revolutionaries are armed that heavily in such a situation?

X: We don’t see a lot of it, by our standards, and a lot of it is posturing for the sake of an image. Gun culture is also far less of a thing on the left, or even in anarchist circles.

Much of the “gun control” legislation that has been passed historically serves to disarm the most marginalized people, not least of all Black militants. In the state of North Carolina, for that matter, where it is legal to walk around carrying a gun, a group of black men were recently arrested for doing so at a protest, while there were many instances of white conservatives showing up armed and shaking hands with police.

When it is more than a symbolic gesture toward militancy, though, it often shows how much of a disadvantage those against the establishment are at, since even civilian establishment supporters are much better armed than us and often more willing to use violence. In a larger sense, we see a far-right tendency among mass shooters who obviously cannot be reasoned with. As such, it should mean that anarchists should be better armed and trained, but there are also a lot of hurdles to legally being allowed to carry a weapon most places – including police approval in our city (for which you can be denied based on “character” alone).

What comes next: generalized insurrection, civil war or smart dictatorship?

X: The United States has been extremely successful in pacifying its citizens over the last century; even those moments of rupture that do occur usually serve as more of a pressure release valve followed by reforms that sneak in additional criminalization of protest tactics (i.e. The Anti-Riot clause of the Civil Rights Act of 1968). The surveillance state continues to expand, furthering a smart dictatorship as democracy, but tensions continue to build.

The proliferation of radical ideas (i.e. abolition) in the mainstream is a useful basis of discussion, but as always it’s coupled with a demonization of anarchists, limiting our impact.

Unfortunately, even though I never want to defer to politicians or their lackeys (voters), I think the presidential election in November will be a deciding factor. If the incumbent is reelected we might see attempts at insurrection, whereas if he loses we might see armed white supremacists take the streets trying to kick off a civil war – barring other significant crises derailing everything before then.

August virtual anarchist discussion: Cyber-nihilism

from Viscera

Join us Saturday, August 1st for our next virtual reading discussion and hang-out! We went into the woods with Seaweed last time, and this time we’ll be reading something… a little different.

There is no human nature, whether that be a natural state of “wildness”, or killing each other if there’s no State, or cooperating perfectly in mutual aid in an anarcho-communist society, or whatever. Cyber-nihilists reject all essentialism and are viciously misanthropic, and therefore we also fully support the proliferation of technology. Let it cover the Earth’s surface until there is nothing that is not a part of the Wired, let Nature complete its next metamorphosis into something more sublime than anything to exist yet.

Our next reading is Hello from the Wired and its afterwords by n1x. You can find the essay on the anarchist library here – the afterwords are on their website along with the essay in hot pink text. You can also find it in aesthetic zine form with lots of screenshots from Serial Experiments Lain here.

As usual, we’ll be meeting on jitsi in room Viscerapvd – the password changes each time, so contact us beforehand! Casual discussion from 1:30-2:30, reading discussion until 4!

Anathema: Volume 6 Issue 5

from Anathema

Volume 6 Issue 5 (PDF for reading 8.5×11)

Volume 6 Issue 5 (PDF for printing 11×17)

In this issue:

- Keeping The Embers Hot

- What Went Down

- Lore Blumenthal’s Case

- Abolish The Police?

- Mass Motives (End Notes Review)

- Touch The Sky Review

- Greek Solidarity With USA

- FAI-FRI Call To Action

- Reparations As A Verb

- Annual Week Of Solidarity

- Running Down The Walls

Mid-July virtual anarchist discussion: land and freedom

from Viscera

Join us Sunday, July 19th for our next virtual reading discussion and hang-out! We’ll be reading Seaweed’s Land and Freedom:

Drawing from histories of rebellion, Seaweed begins a conversation with fellow anarchists about struggle, strategy, subsistenence, or past, and our future. What kind of communities do we need to exist to support long-term rebellion against Capitalism? What would it mean to create insurrectionary movements for subsistence? What kind of relationships might arise from long-term ecologically-based struggles? This book is an invitation to explore these ideas.

(Note that this is the full version, not the excerpts uploaded to the anarchist library – you can also buy the book in full from us or Little Black Cart)

Related, optional pieces to consider are Seaweed’s appearance on The Brilliant as well as Bellamy Fitzpatrick’s An Invitation to Desertion for comparison (or here for the pdf).

As usual, we’ll be meeting on jitsi in room Viscerapvd – the password changes each time, so contact us beforehand! Casual discussion from 1:30-2:30, reading discussion until 4!

BreakOut: Dispatches on Resistance to the Pandemic Inside Prison Walls #4

from It’s Going Down

As prison abolitionists, many of us have been fighting in solidarity with and alongside imprisoned comrades for many years. But in the post-outbreak world, the COVID-19 pandemic has birthed new and increasingly complicated challenges, as the virus spreads like wildfire and the State locks prisoners down, moves them, and we become increasingly cut off from those we are in direct contact with.

Despite this, we have seen some of the most inspiring organizing on both sides of the prison walls in the past few months as thousands have taken to the streets across the so-called US to demand #FreeThemAll and prisoners have launched uprisings and hunger-strikes. Now, as COVID-19 cases again pick up steam and the rebellion enters into its second month, moving forward we want to take stock of existing strategies and tactics; discussing what has worked, and what needs work.

Towards that end, we reached out to folks involved in Oakland Abolition and Solidarity (formally Oakland IWOC) and the Philadelphia chapter of the Revolutionary Abolitionist Movement to find out what’s been working in their regions and how we can build off of these lessons.

IGD: In some states, economies are beginning to re-open. How do you see this impacting what will happen inside prisons? Are prisoners a part of any of the phased re-opening plans in your state (if they have any), and what do you expect to happen to the small amount who have been furloughed from their sentences?

Oakland Abolition and Solidarity: Transfers between prisons are restarting, they were suspended for approximately 2 months. Some facilities never really instituted plans that allowed for social distancing. One has had 3 confirmed CO cases, though we suspect more. Others have had larger outbreaks and a number of deaths. Very little else was done system wide other than cancel all visitation. Some measures like removing every other phone in order to create more distance are experimental and end up further limiting people’s access to resources and connections without alternatives. Other measures have been instituted like staggered meal times. Public Information Officers are also not answering their phones or returning calls.

CA released a smaller number of people relative to the size of its population, and there’s reason to believe that the Governor of California has exaggerated the amount of people released during the crisis.

Beyond that, people have widely expressed the really intense psychological effects of just knowing that the COs are going in and out everyday with little or no screening, and that they are the only vectors for exposure. So it’s up to the care and discretion of guards to what extent prisoners are exposed. This is cause for extreme concern, even maddening.

Philly RAM: As state economies re-open there will be a higher demand for goods produced via prison labor; the conditions in which that labor takes place further increases the likelihood the already-vulnerable will contract the virus. Even in Pennsylvania (which is slowly easing up in the southwest) prisoners are being made to manufacture masks, antibacterial soap, medical gowns, and disinfectant.

IGD: For those of us on the outside, we’ve been experimenting with different tactics while also trying to maintain social distancing. The car blocs and caravans were an ingenious work around to that dilemma for the current moment. But what comes next? How do we create opportunities for mass pressure campaigns that work beyond just a honk-in or call-in?

Philly RAM: COVID-19 makes organization and action even harder than before. We believe that we can make progress using small IRL demonstrations and things such as lock-ins in addition to call-in campaigns and caravans. But what’s even more important is getting as much info and resources as possible inside the prisons.

IGD: A critique we have heard from people inside, is that our struggles in their eyes have at times reinforced the idea of there being good/bad prisoners – this playing out through the process of demanding and petitioning for selective release. How do we as abolitionists move forward with a demand to “free them all” without ultimately relying on piecemeal concessions?

Oakland Abolition and Solidarity: One of our points of unity reads, “We reject labels given by the State such as ‘guilty,”criminal,’ or ‘gang member.’ We do not choose who we work with based on these or other simple moralistic designations.” We would certainly add “violent/non-violent” “safe/dangerous,” and any other such designation to this list. It is built into our practices and language to ignore the myriad ways that the State pits prisoners and all people against each other. We reject all reforms or policies that reinforce these or further entrench these hierarchies. Free them all is and has always been our cry. Prioritizing older and more compromised/ vulnerable folks may be acceptable in this time, but never give an inch to the narrative that some prisoners are “safe” and others “dangerous” recognizing that these narratives ultimately redound to the benefit of the carceral system.

Philly RAM: A concept we’ve discussed in the effort to counter hierarchical tendencies is that the carceral state and its culture criminalizes so many aspects of our lives (whether we’re inside a physical cage or not). That the capitalist State designates who is within its bounds and worthy of moral consideration. This is a point of solidarity we share with those inside the prisons – to differing extents we all find ourselves against the US carceral system.

IGD: As the pandemic drags on, Black and Brown communities are shouldering the majority of the deaths and the heartache – this is most clear in rural communities where epicenters have been inside prisons, jails, detention centers, meat and produce packaging plants and warehouse style working conditions. These spaces all share the reality of being largely hidden from “the public.” How do we help keep these struggles connected to each other and in the forefront of the minds of people that are already overly inundated with media?

Oakland Abolition and Solidarity: Collaborative, real time, and engaged content. Seeking and building active collaborations that are rooted in a recognition of the connection between struggles. Example, looking for and seeking to support mutual aid structures that are popping up in “prison towns.” Fusing a meaningful, material backbone for ongoing conversations and collaborations.

Philly RAM: Keep communication open with comrades on the front-lines, then plug in to fulfill the needs of the people. Some good examples we’ve seen are medical fund campaigns, supporting striking workers, and gathering clothes/tools necessary for folks exiting prisons right now (among others).

IGD: Based on what you have seen either in your own organizing or those of comrades, what have abolitionists done in the past few months that has had the most impact and generated the best results? Also, what walls or limits, either in terms of the State refusing to budge or our own capacity, have we run up against in our organizing that we must now figure out how to get over and move beyond?

Oakland Solidarity and Abolition: It feels like the State is winning right now and setting the tempo, but our job remains unchanged. However, success can’t only be measured in whether or not the State bends to the will of the people. People building frequent, reliable, and solid relationships and communication channels with people in our county jails over the last few months has been extremely impactful. People inside having access to a larger media platform to have their stories heard, taken seriously, and acted upon creates empowerment, and greater collaborations that can be built on.

One weakness that we’re observing though is the need to be more creative with taking care, providing support, thinking strategically, and supporting accountability in our collective organizing. There are fewer built in chances to see, check-in with, and support each other. There’s more isolation, both inside and out. We need to be more vigilant about filling those gaps, and it takes more intention. Moreover, the landscape is shifting really rapidly, and it can easily overwhelm people’s personal capacity.

We must continue fostering collaboration and collectivity. It’s time to be more vigilant and disciplined.

Philly RAM: From what we and our comrades have done and seen and seen from others, it’s been the commissary drives, online workshops, and education opportunities have really served to bring people together and uplift the spirits of those inside or outside. Establishing skills in care work and teaching each other help us for any future situations that might arise.

IGD: In your own words, in the current COVID-19 period, what do you think comes next in the fight for abolition?

Oakland Solidarity and Abolition: Desperate times call for desperate measures. The current moment shows us who, what, where, and why of what ‘desperate’ is. It’s our job as abolitionists from wherever we are to fight the desperation, death, and indignity around us and our neighbors.

Everything about this world is becoming more naked. Violent mechanisms survive best in the dark and they’re finding fewer places to hide. I think our job is to be loud and quicker about everything that happens, and be creative about illustrating and interpreting the shifts. But ultimately this is just a piece.

Report back and reflections on the Juneteenth anti-cop anti-prison noise demo in Philly

from Anarchist News

Even though there’s been active protests going on everyday here since May 30th, it feels like things for the most part are becoming more and more tame. There’s still a lot of momentum but with it is a strong fear it’ll be overtaken by the popular liberal agenda or suppressed by state repression. Nonetheless with a curiosity of what direction things will take, and with rather low expectations I showed up to the call for the ftp noise demo..

Most folks show up to the meet-up mad late. There were conversations around not having enough numbers, if the time was called for too early and if we should wait longer, make moves, or go home. Lots of hesitations and indecisiveness. Fortunately despite the demo being publicized on the internet, there was no cop presence at the start, and the 25 of us decided to proceed.

Even while moving, things started off a bit awkward and quiet. We rushed through the streets towards the federal detention center. Graffiti went up on the walls and some cop vans, and when we got to the FDC things got LOUD. There were tons of fireworks and smoke bombs, fuck prisons graffiti was written on the ground for the prisoners to see, there was yelling and banging on street signs. There were a few chants but for the most part they were pretty minimal. The folks inside were hype to see us, they were flashing their lights and banging on windows. Their reactions reassured a lot of the trepidations some of us had had about coming out after all.

Once we finished with the louder toys, we didn’t try to stick around since a small squad of cops had showed up outnumbering us. We had a hasty, sloppy dispersal but everyone made it out alright and in good spirits.

After the demo I was left with a few things on my mind:

Noise demos are really cool opportunities for people with less street experience to get their feet wet with a little more risk. Because they’re a slightly more escalatory than the common protest marches, but aren’t as scary as heavier attacks, they give folks a greater sense of power and practicality to navigate moving through the streets together in riskier situations.

Regardless of what type of action we show up to it’s important to come with our own personal goals and a readiness to adapt to the goals of others around us.

One way to stay ready is to always use best practices to conceal our identities. Whether that’s making sure we’re covered up before we’re near any cameras or cops, or wearing gloves whenever we use illegal objects that might get left behind. It’s important we stay off the radar, unrecognizable and untraceable.

When moving together we really gotta get better at keeping it tight and not panicking! When were too spread out at vulnerable moments it puts us more at risk. Cops trailing us doesn’t always turn to cops chasing us. When we run away unnecessarily we open ourselves up to being more vulnerable. It’s important to assess when it makes or doesn’t make sense for us to run.

Lastly, it’s exciting to imagine all the possibilities of what we could get away with in a group that big when there’s no cops around!

In times like this, where repression is coming down extra hard it’s especially important to show solidarity and counter isolation.

Shout out to all the angry ones turning their anger into action, directing it to revolt. Solidarity to all those recently captured by the state, you’re in our hearts and your actions were courageous.

I hope that we can spread and keep the momentum of the recent uprisings directed towards the police state and it’s prisons, because without their total destruction we will never be free.

Towards the destruction of the state, it’s cages and it’s reinforcers.

Towards the creation of something better than anything they could ever offer us.

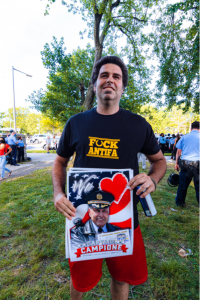

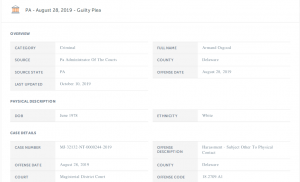

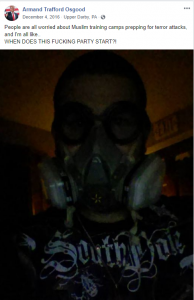

Meet Proud Boy Armand Trafford Osgood

from Philly Proud Boys

Armand Osgood is one of the newer recruits to join the ranks of the Philadelphia Proud Boys, first seen publicly with them in 2020 though he may have joined earlier. His first public appearance was with persistent nuisance Scott Presler, during a cleanup of the city under the guise of community service, though it goes without saying these guys don’t give a shit about communities that aren’t their immediate circle of white friends.

He seems to have really weaseled his way in among the ranks of Sonny Sullivan and Zach Rehl, the two chumps who still remain largely at the helm of the Philly Proud Boys. He can be seen hanging out with them in April.

He has most notably made a prominent appearance at the ongoing conflict around the Christopher Columbus Statue in South Philly. He appeared alongside the large unruly mob of entirely white South Philly residents who had spent days hurling slurs and hate at minorities who dared to come near them and physically assaulting many people as police stood by. He was personally seen spitting on people, which carries extra weight as a heinous act during the coronavirus pandemic.

He is also decidedly pro-coronavirus, taking an active role in the Reopen protests in Pennsylvania, trying to rally people to the diminutive Philly protest. If he showed up no one knows or cares because it was such an impotent event.

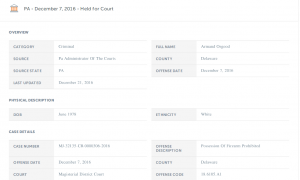

Despite seeming to love cops, Armand cannot seem to be able to follow the law himself, with a dense history of 14 charges and arrests over just 4 years, for everything from drug possession, harassment, weapons violations, and public drunkenness (While Gritty doesn’t think someone’s criminal history should be a judge of their character, they find it a bit hypocritical that someone who is constantly getting in trouble with the law comes out and stands up for the cops. Can you say subservient bootlicker? Why would you support the cops if you can’t even follow the law? Is it because they harm the demographics you don’t like with impunity?)

Armand seems to be cut from the cloth of right wing violence role players, though he is doing what he can to make those fantasies seem real. In one facebook posts he dreams of a day where he can go out and shoot Muslims. He also has their archetypal fixation on Benghazi.

And it’s no surprise that he has turned out this way, as other members of his family are involved in militant right wing movements, like his brother Alain Osgood, who attended a “March Against Sharia Law” in Harrisburg in 2017 alongside Militia members. This Rally notably attracted a number of outright neo-nazis including members of Vanguard America (The group responsible for murdering Heather Heyer in Charlottesville in 2017).

His last known place of work was Charles Gratz Fire Protection Co Inc., though it is unknown if his employment has been affected by the Coronavirus Pandemic. It may be worth checking in with them just in case, at (215) 235-5800, to let them know a violent and active member of a hate group works for them. However, it is most likely that he works as an independent contractor currently. Any tips are appreciated!

Also Armand, not sure why you think joining a hate group would help with your custody battle. Happy Fathers’ Day, dickbag.

The Riot Manual

Submission

Definition. A riot is a form of popular warfare in which a crowd engages in a variety of illegal and violent activities. These can include property destruction and looting; disrupting lines of transportation; street fighting against the police and/or military. Like all forms of revolutionary warfare, those who participate in riots assume the risk of injury, imprisonment, and/or death.